Unit 1 Online Study Guide

Learning Unit 1: Analyse the context of ECD programmes

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to analyse the context of ECD programmes. You will be able to:

- Ensure that the analysis clearly identifies the developmental stages and particular needs of all the children within the given context

- Ensure that the analysis is informed by Early Childhood Development (ECD)-related frameworks

- Ensure that the analysis identifies the key factors that could have an impact on the programme

- Ensure that the analysis is informed by previous evaluations of activities, and assessments of children

- Ensure that the analysis is sufficient in scope and depth to inform the development of the programme.

Analyse the context of ECD programmes

The ECD learning programme is the educational heart of the ECD centre. Think for a moment about why children attend an ECD centre. You may identify reasons like these ones:

- To be nurtured and cared for in a safe place

- To interact and socialise with peers

- To be stimulated and encouraged to learn and develop

- To learn through play in a flexible, creative learning environment that treats each child as a unique individual

- To learn self-reliance and independence

- To encourage exploration and self-discovery through learning

- To acquire the early building blocks for life skills, literacy and numeracy skills.

The aims of the ECD centre and parents of young children for the young children who attend an ECD centre are similar to these listed above. How can the ECD practitioner ensure that the ECD centre achieves its purpose? He/she does this by designing an ECD learning programme.

Let’s use a metaphor to make this concept of the ECD learning programme clearer. Imagine that you are going on a journey by train. The purpose of your trip is to travel from Cape Town to Durban in a safe and comfortable manner, perhaps learning more about South Africa en route. For this journey, many elements must be in place for the trip to succeed: wheels, carriages, seats, windows, a driver, an electricity supply, a train line, a schedule or timetable, scheduled restaurant or station stops to buy refreshments, ablution facilities and so on.

In the same way, an ECD learning programme includes all of the elements required for young children to learn, play, grow and develop in a safe, caring environment during early childhood.

Every ECD context is different. For example, one ECD centre may be very small, providing care for the babies of six working mothers in a middle-class suburb; another one may offer morning only care, but may be large with playgroups in all the age categories. Can you see why the ECD learning programmes for the two centres would need to be different? In Unit 1, you will see that the first step in preparing an ECD programme is to understand and analyse the context in which we operate. We have to look at our micro-environment within the ECD centre as well as our macro-environment, which includes our immediate environment and the country as a whole.

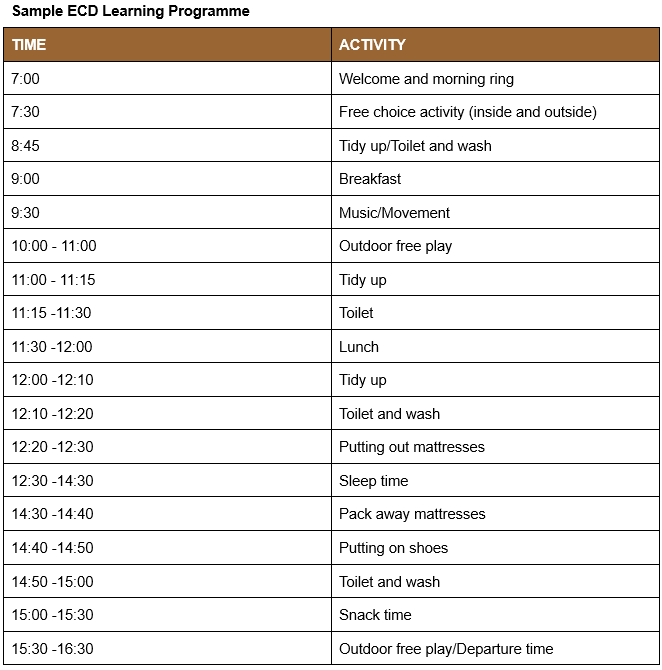

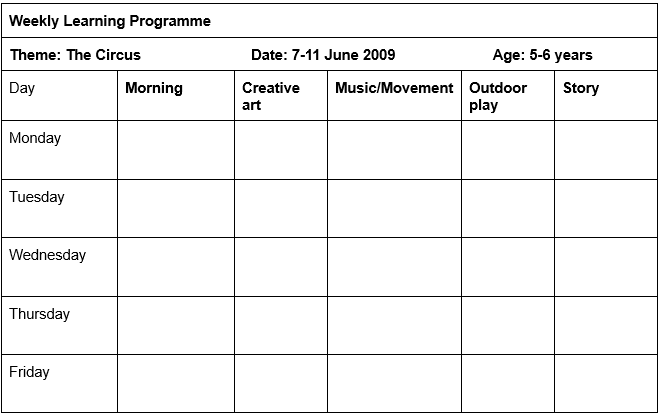

Every day at the ECD centre, the ECD practitioner uses a programme that shows the activities that will be done that day. Based on this programme with activities, the ECD practitioner can identify the resources that will be required for that day.

Action research cycle

The action research cycle will be used throughout this programme. Action research is one of the key strategies which are being used across all stages of the Professional Learning Continuum in a range of programmes. During action research investigations are being done by educators for educators with the aim to improve student outcomes.

Action research

- Tends to be cyclic – similar steps tend to recur, in a similar sequence

- Participative – those who are working within the research are as partners, or at least active participants, in the research process

- Qualitative -- it deals more often with language than with number (quantitative vs qualitative)

- Reflective – critical reflection upon the process and outcomes are important parts of each cycle.

The cycle consists of the following steps:

Planning

- Identify the issue to be changed.

- Look elsewhere for information. Similar projects may be useful, as might professional reading.

- Develop the questions and research methods to is used developing a plan related to the specific environment. In the school setting this could involve personnel, budgets and the use of outside agencies.

Acting

- Testing the change following your plan.

- Collect and compile evidence.

Observing

- Analyse the evidence and collating the findings.

- Discuss the findings with co-researchers and/or colleagues for the interpretation.

- Write the report.

- Share your findings with stakeholders and peers.

Reflecting

- Evaluate the first cycle of the process.

- Put into practice the findings or new strategy.

- Revisit the process.

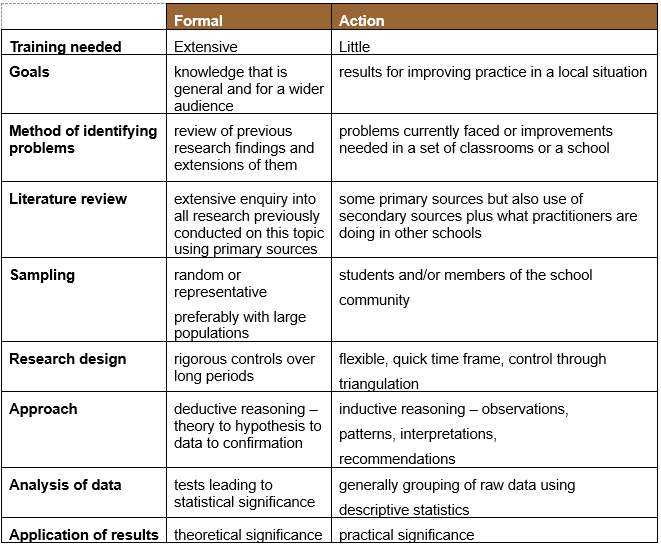

Below is a table that compares action vs. more formal methods:

Educators should use action research because:

- It deals with their immediate challenges on a personal level, not someone elseâ€s

- It is immediately implemented — or whenever they are ready — providing immediate results

- This research provides them with opportunities to better understand, and therefore improve, their educational practices

- It is a process: action research promotes the building of stronger relationships amongst staff

- It provides educators with alternative ways of viewing and approaching educational questions providing a new way of examining their own practices

1.1 Ensure that the analysis clearly identifies the developmental stages and particular needs of all the children within the given context

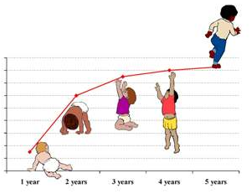

As an ECD practitioner, you know that babies go through various stages of development on their way to becoming toddlers and then young children. You know that a group of babies has very different learning and developmental needs to a group of toddlers or young children. You know that although the developmental stages are grouped according to their ages, each baby, toddler and young child is unique and develops at his or her own pace.

This means that, while a group of children will have certain learning and developmental needs, each child within the group will also have his or her own particular needs. You need to use this information about group needs and individual needs to identify the types of activities that are suitable for your playgroup. In this lesson you will learn how to conduct an analysis to identify the needs of your group and each individual in the group. You will also learn how to use that analysis to identify the types of activities that will meet the needs of the babies, toddlers or young children in your care, both as a group and as individuals.

What are learning and developmental

needs?

Children grow, develop, and learn throughout their lives,

from birth to adulthood. As you know from Module 2, babies, toddlers and young

children move through recognisable stages of growth and development, according

to experts such as Piaget, Whitbread, Erikson and Vygotsky. These experts tell

us that during each stage of development a child has different learning and

developmental needs. So, what are learning and developmental needs? They are

the skills children need to learn, acquire and develop at a particular

developmental stage in their lives.

- Are they able to identify three basic shapes and fit them correctly in a shape puzzle?

- Are they able to identify objects of different sizes such as biggest, longest?

- Are they able to copy objects that are made of blocks?

- Are they able to recall up to three numbers and remember where objects have been put away?

- Are they able to concentrate for at least ten minutes on one activity?

a. Language development

- Are they able to describe simple actions when paging through a book?

- Are they able to use the plural such as "dog – dogs" and make negative statements such as "I don’t want to"?

- Are they able to give their first and last names and understand longer more complex sentences?

- Do they ask a lot of questions and use functional sentences such as “I am hungry�

b. Social and emotional development

- Are they able to understand what is allowed and what is not?

- Are they able to sympathise with friends who get hurt?

- Are they able to dance and sing in small groups?

- Are they able to share and take turns?

This sample questionnaire has been developed in the plural form (for more than one child). To collect information about an individual child you can simply develop a similar questionnaire with the questions in the singular form for each individual child in your playgroup – for example: "Can (s) he sympathise with friends who get hurt?†At the top of the questionnaire you would fill in the child’s name and his or her exact age. For example, the cognitive development section of an individual questionnaire would look like the one below:

1.1.1 Development of children

When you analyse the context for your ECD learning programme, your analysis should clearly identify the developmental ages, stages and needs of all the children within the playgroup. This understanding will help you later when you prepare your ECD learning programmes. As you know, it is important that the ECD programmes that you prepare for young children are appropriate to their ages and stages of development. This is known as developmentally appropriate practice (DAP).

Age-appropriate

programmes

The developmental stages are grouped according to the ages

of the babies, toddlers and young children. However, we also know that each

baby, toddler and young child is unique. Each child grows and develops at his

or her own pace. Each child will go through each developmental stage whenever

it is right for that child. We know we need to be sensitive to each individual

childâ€s needs, to help each child develop in a way that is just right for him

or her. All this knowledge will help you to identify activities within a daily

and/or weekly programme that support the development of the babies, toddlers

and young children in your playroom. This knowledge will also help you to

identify the resources and space you need for these activities.

We can all agree that children at different ages and stages of development have different needs. We cannot have the same expectations of a five-month-old baby as we do of a three-year-old child. In order for children to feel happy, secure and supported, we need to cater to their needs. The various theorists such as Piaget, Erikson and Vygotsky studied particular areas of interest but there are overlaps. The major point of agreement, though, is that play is a way to learn.

“To re-enforce learning, we always apply the skill we have learned, hence we learn by doing.â€

No matter the age of the child, your daily planning needs to include time for the child to play freely and spend time to explore his/her environment in order to learn.

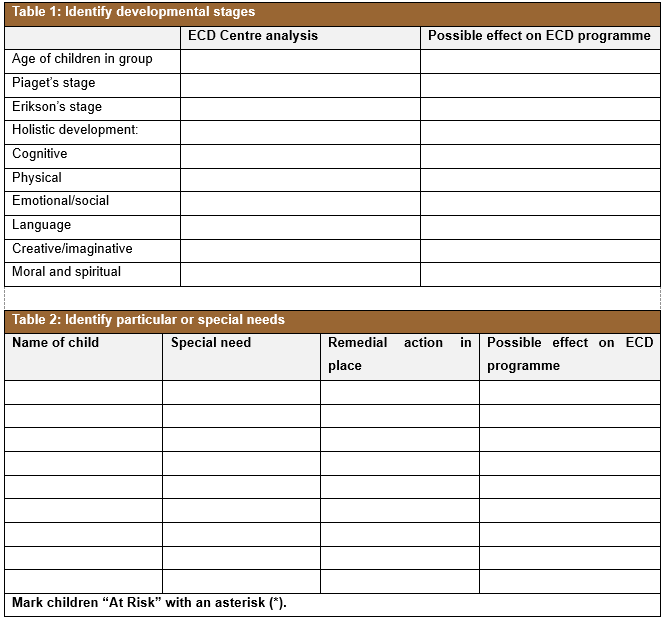

Here is an example of how you would identify the development stages and special needs of the children in your charge:

Step 1: Identify developmental stages

- Refer to Table 1 below

- In order to complete the table, you will have to gather information through a combination of observation, getting to know the children in your chosen group, interviewing the ECD practitioner and possibly the principal and, if possible, also interviewing the parents/caregivers

- Complete the table for the ECD playgroup.

Step 2: Identify particular or special needs

- Look at Table 2

- Investigate the history of any child with special needs by making enquiries from ECD practitioners and the family and find out what remedial measures (corrective steps) have been taken. We suggest that you use a class list to note each child’s special needs and remedial action taken

- Complete the table for the ECD playgroup (below).

Step 3: Identify the needs of particular learners:

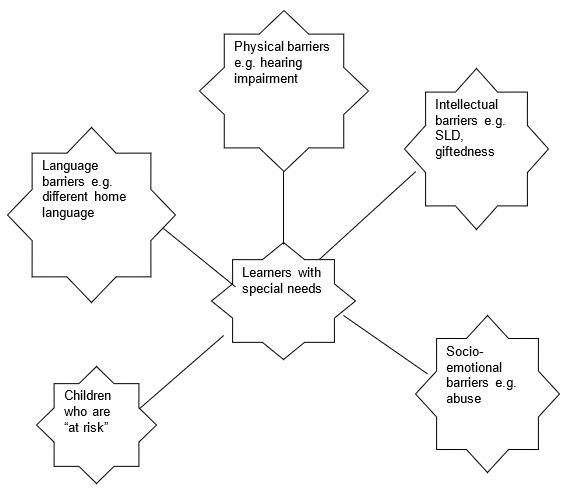

In South Africa, we have an inclusive education system. This means that learners with special needs (for example, a child with specific learning disorder (SLD) or dyslexia) are integrated into the mainstream of the education system. The mind map below shows the different categories of learners with special needs:

According to Education White Paper 6 Special Needs Education, one of the most significant barriers to learning for special needs is the learning programme. Barriers to learning arise from different aspects of the learning programme, such as:

- The learning activities (in other words, how learning happens)

- The main language of the ECD playroom

- How the ECD playroom is organised and managed

- The methods and processes used in facilitating

- The space and the time available to complete activities

- The learning materials, resources and equipment that are used

- How learning and development is assessed.

Within the context of inclusive education, each child is viewed as a whole person with a barrier (obstruction) or barriers to learning. It is your task as the ECD practitioner to adapt the ECD programme and your presentation techniques to also make provision for the special needs learner. Every child is different, and a child with a specific barrier to learning will have unique challenges in the ECD playroom. As the ECD practitioner, you must first recognise that the child has a special need, understand the nature of these needs and then make appropriate adaptations to the ECD programme. For example, if a child has a hearing impairment (barrier), you may need to ensure the child sits next to you during story time; you may need to repeat instructions clearly to the learner or appoint a helping partner to repeat instructions.

The key factor is for you as the ECD practitioner to show that you are willing to respond, adapt, be flexible and ensure that the child with special needs feels safe and happy in the ECD environment. Remember, every disability is different; every child is different. There are differences in the kind and extent of any given disability and also differences in how people cope with it. Different families can have children with similar challenges (disabilities) but they learn to cope very differently depending on their own situations, finances, and the support they get from other family and friends.

Children with special needs can lead positive, happy lives and bring joy to themselves and many people. Quality of life is about the child blossoming at various levels. These include being safe and comfortable, having experiences to enjoy, feeling that he/she is a lovable person, and having some skills and abilities that he/she can feel proud of being able to perform.

Needs of children at risk

"At risk" children are those children who are, while currently healthy, at risk of developing learning challenges such as emotional behavioural problems or physical disabilities in the future. Babies or children from poor backgrounds or who are exposed to drugs, abuse, neglect and those with genetic pre-dispositions to mental illness and physical disabilities are described as being at risk. Action research can be very beneficial here as it provides an immediate platform for assistance.

I. Conditions that can indicate that a child is at risk include:

- Low family income

- Divorce or separation

- Violence or neglect in the home or community; low parent education levels and/or underage parents

- Low birth weight

- Parent chemical addiction

Children from low income families often need additional care and their parents may need more help by means of educational talks and/or support, for example on how to apply for grants; or parent education programmes on topics that range from coping with abuse by their spouse (husband or wife) to how to use recycled or everyday items to encourage the child’s development and curiosity.

An example of how children at risk would affect your daily programme plan is that children who are hungry might have to start the day off with a snack or children with no proper ablution facilities might need to be bathed at the ECD centre. Those using public transport may need extra time to sleep during the day, because they had to wake up early. Generally speaking, the practitioner would need to closely monitor the emotional development and wellbeing of "at risk" children.

II. Coping with prejudice

Our society often labels children with

disabilities as "different" or damaged or not good enough. As a

result, children with disabilities are at risk of being teased, bullied or ill-treated

by other children at the ECD centre. You, as the ECD practitioner, need to have

a zero tolerance policy for bullying, blaming and shaming of any learner,

including those with barriers to learning. You also need to have an unbiased

(fair and impartial) approach towards the children in your care, and treat

children equally regardless of their gender, race, language and learning

barriers. In this way, you demonstrate an attitude that is open and inclusive

to the children in your care towards bullying in any form. Encourage

parents to adopt this attitude as well.

Remember! While young children often reflect the prejudiced and discriminatory attitudes of their society by treating learners with special needs in unkind ways, they can also learn values of empathy, compassion and helping others. Let them learn that from you. This is an important part of children’s moral or spiritual development.

Here are some strategies for handling prejudice in the ECD centre.

- Create ECD policies and active practices to deal with discrimination. These should include zero tolerance towards bullying in any form

- You might ask the parent to tell the class about their child and answer any questions

- If teasing is a problem, you might help the child to learn ways to respond to it by modelling responses for her. You might practise them with her, for example by holding her head up and ignoring the teasing, pretending there is a magic screen around her so it canâ€t hit her, staying near a group and so on

- Let the child know that if she is being bullied it is important to always tell an adult

- Perform an action research incident with other staff members and even the community.

III. Identifying particular children’s needs for ECD programme purposes

Questions you can ask to identify children’s needs

Start with identifying learners with particular or special needs:

- Are there learners with special needs, for example SLD, hearing impairment, giftedness, shyness?

- Are there learners who are at risk?

- What do you already know about this special need or at risk circumstances?

1.2 Ensure that the analysis is informed by Early

Childhood Development (ECD)-related frameworks

The ECD learning programme is often developed based on a particular model of early childhood education. There are many different programme models available. In your search for employment in early childhood development, you will undoubtedly come across many different techniques for teaching young children. If you observe different playschools, you will note differences in the ECD practitioner’s role; the playschool’s objectives, the scheduling of time, the arrangement of the playroom and the type of materials that are available.

We will introduce you to five different programme models below. These models can be used from playschool through Grade R, and the Foundation Phase. Some models can be used throughout formal schooling. As you read the following section, take note of the important differences between the various programmes. This will help you when you analyse your context. The models we will look at are:

- The open-plan model

- The high scope model

- The academic or direct instructional model

- The Montessori model

- The eclectic model.

A. The open-plan model:

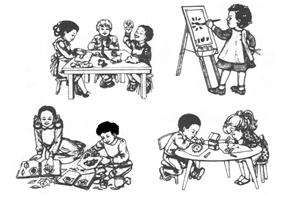

The programme emphasises that the teaching approach for children should focus on co-operation, sharing, making free choices and creative play. Children learn best through interactions with peers and adults in an environment that allows maximum exploration and discovery and experimenting.

In this type of programme, children are provided with many activities to choose from:

- Creative activities

- Discovery

- Make-believe

- Blocks

- Educational

- Books

- Sand and water

These are some of the material and equipment provided. Having fun-filled educational activities available provides motivation for learning. The ECD practitioner’s role is to be caring and supportive when using this material and equipment.

The daily schedule is structured but flexible. Independent and small group work is encouraged, and many activities may take place at the same time. Reading and writing are an important part of the programme too. The ECD practitioner often reads to children, and they are encouraged to write their own stories. The teaching is arranged around themes, which may include topics such as organising chores, cooking, caring for pets and building. For example, a simple task such as making biscuits can provide children with the opportunity to count, measure, weigh, observe, read and write.

B. The high scope model

The cognitive-oriented curriculum (previously known as the Perry preschool), was developed by David Wilkart and others at the High Scope Institute in Ypsilanti, Michigan. It relies heavily on the teachings of psychologist Jean Piaget. As we discussed in Module 2, Piaget recommended that children should be actively involved in their own learning and learn through their interactions with people and things. You will remember that Piaget proposed the following series of developmental stages for children:

- Sensori-motor (birth to two years)

- Pre operational (two to seven years)

- Concrete operational (seven to eleven years)

- Formal operational (over eleven years)

Children reach these stages in a predictable sequence, one after the other. You will remember, however, that the age at which children reach these milestones may vary from child to child. The cognitive-oriented curriculum promotes active involvement in learning. It also recognises the different developmental level of each child and provides activities that are appropriate to each child’s level.

The cognitively-oriented curriculum, as its name indicates, includes a strong emphasis on children’s mental development. The playroom is arranged so that there is a central, open area for group activities and games. Around the edges are play areas and quiet areas. The daily routine is important, and ECD practitioners and assistants are expected to follow it. The routine includes planning time, activity time, cleaning-up time, recall time, snack time, a second recall time, outside time and circle time.

During planning time, children make and present their own plans for the day. They are asked to communicate about where they will do activities, what resources they will use, the sequence they will follow to complete the plan and the problems they might experience. There are countless activities the children may include in their plans – for example, planting seeds, drawing a picture, reading a book, or putting on a skit (a humorous imitation).

As children mature and gain writing skills, they can begin to communicate their plans to others by means of pictures and written works. Planning involves children in their own learning and is considered to be central to the programme. During recall time and small-group time, children meet with the ECD practitioner in small groups to share and discuss their activities. At some point during the day, the ECD practitioner will also observe each child doing certain tasks that were chosen by the ECD practitioner.

The cognitively-oriented curriculum stresses active learning, language, seriation (putting things in series), numbers, spatial relationships, experiencing and representing, classification and time. Children accomplish these learning goals in different ways: by manipulating and transforming materials; by describing objects, events and relationships; by recognising objects by sound, taste and touch; by making models; by sorting and matching objects; by making comparisons; by putting countering (putting opposite one another) and rearranging objects and by understanding time units.

The practitioner’s role in the cognitively-oriented curriculum is as follows:

- To assess what developmental stage the child has reached

- To provide an environment where children can become decision makers and problem solvers

- To guide children in their learning.

The ECD practitioner must know the developmental level of each child, so that he or she can provide learning experiences that match the child’s developmental level.

C. The academic or direct instructional model

The academically-oriented preschool programme was developed by Carl Bereiter and Siegfried Engelmann at the University of Illinois, USA. It is now known as the Bereiter-Engelmann model or DISTAR. This programme is based on the idea that it is not good educational practice to wait for academic readiness to develop in children, especially for disadvantaged learners. ECD practitioners who support the academic programme believe that children can be encouraged to achieve well in academic settings when academic performance is positively reinforced. You will see that this programme is much more structured than the programme models we have discussed so far.

The academically-oriented programme emphasises instruction in reading, writing, language and arithmetic. The objective of the programme is to help children acquire very specific skills in these subjects. Children are organised into groups of three to eight for instruction. The groups are organised according to ability. During the course of the day, children attend “classes†in each of the subject areas.

The ECD practitioner follows specific instructions from the programme handbook, and works with the group on specific skills. The pace is fast and there is little tolerance for misbehaviour; and children are expected to work at the pace of their group. Tasks are taught with a lot of repetition, drill exercises and hand-clapping to mark out the rhythm of language patterns.

The ECD practitioner carefully arranges questions in sequence in order to get the correct responses from the children. Correct answers are rewarded with praise and prizes (such as biscuits). Incorrect responses are not accepted, and the problem is asked again and again until a child gives the right response. You will find that there are very few of the “play†materials found in other types of playrooms, because they are seen as distractions to learning. The playrooms are uncluttered and toys are limited. The materials used in this programme include paper, pencils, chalk, puzzles, books, crayons, miniature houses and model farm animals.

In the academically-oriented programme, time is tightly scheduled and certain subjects are taught within specific time periods. Children are expected to be quiet and controlled, and free play is limited. Talking out of turn is discouraged, and children are expected to remain seated during work periods. Following rules is very important. A child who misbehaves may be punished by being isolated.

D. The Montessori model

At the turn of the century Maria Montessori implemented an early childhood education programme that has been widely adapted in the USA. There are also Montessori schools in many other countries; including SA. Montessori believed that a child’s development is an unfolding of natural aptitudes. These aptitudes need certain environmental conditions in which to develop. If these conditions are provided, children will develop to their full potential. The Montessori approach emphasises an open playroom in which children can choose their own activities. The role of the ECD practitioner is to provide choices that are appropriate to the developmental level and abilities of each child and to show children how to do the activities.

The Montessori model emphasises special learning resources that children can play with on their own in a flexible manner. The resources are arranged in sets that gradually increase in complexity. As children become bored with one set of resources, the ECD practitioner introduces them to the next set, at a higher level of complexity. These resources are of the following three types:

- Academic material (for language, reading, writing and mathematics)

- Sensory materials (for visual, olfactory, tactile and auditory stimulation - in other words seeing, smelling, touching and hearing)

- Daily living materials (for cooking, cleaning and grooming)

The following are some examples of resources you will find in a Montessori playroom:

- Sand paper letters that introduce children to the feel of the letter shape

- Individual wooden alphabet letters that can be used to create words

- Number rods of varying length that represent one through ten and are used for counting

- Graduated blocks that teach counting and sequencing

- Everyday materials such as knives, irons, sponges, brooms and combs, which children use in adult activities

- Command cards with actions such as run, walk and jump printed on them

The child reads the cards and then does what the word says.

At first, the ECD practitioner tells the child how to use the resources. For example, the ECD practitioner shows the child how to take a particular resource from a shelf; arrange the resource so that he or she can play with it, and how to replace it properly. In the Montessori playroom, there is a place for everything, and everything is in place. After this initial instruction, the child will not need the ECD practitioner’s help. The children will play with whichever set of materials they want to, until they are ready for the next level of resources. Children must wait until their playmates are finished with particular resources before they may use them.

The Montessori playroom can be called a prepared environment – a place where children can do things for themselves. A great deal of care goes into creating a nurturing environment. Learning resources must be put in a specific place so that children will know where to find them. Resources with a similar function are grouped together and then arranged in order of complexity or difficulty.

Fantasy is not a part of the Montessori Method. It is believed that children should actually learn to do things that adults do, not just play at being adults. As a result, children in Montessori playrooms will prepare food with real knives, clean and wash dishes, do garden work and other tasks that are typical adult occupations.

E.

The eclectic model

Eclectic childhood programmes are more common than any

other type. "Eclectic" simply means that you use elements derived

from a variety of sources. For example, you may find that even though a

programme identifies itself with one or another particular model, in certain

aspects it may differ significantly from what its founder intended it to be.

Each programme you encounter will reflect the background and philosophy of its founder

and its ECD practitioners, as well as the needs of the community that it

serves.

For this reason, you may find cognitively oriented or Montessori playschools that deviate from the descriptions given above, because they have borrowed elements from other programme models. The eclectic programme is truly a hybrid, that is, a combination created from elements that were borrowed from all four of the basic programme models we have discussed.

There are a variety of frameworks, approaches and models when it comes to the ECD curriculum. While researchers have not yet identified one model as being better than another, it is always important that whatever programme you choose have established goals for children. Educational programmes should be sensitive to the age group of children they serve, and the individual needs of the children in the group.

You should use ECD-related frameworks as a guideline for your programme. In South Africa we also have a national curriculum and national policies available. In addition, there are educational groups and organisations that can help you keep informed about all the policy requirements related to ECD.

1.2.1 Theories of child development and learning

When you design activities that meet children’s developmental needs you will use the theories of child development. For the sake of clarity and organisation, child development is divided into stages. It is important to remember, however, that the age ranges at approximate and flexible in any scheme of developmental stages. Variation in achieving certain milestones, whether they are physical, cognitive or social, is normal. All developmental stages are a guide, but remember that each child is unique, and will develop at his or her own pace.

A learning activity that meets the developmental needs of a particular child is an activity that the child can do with a strong chance of success. Why? Because the learning activity is designed to fit with what the child is able to do at his or her stage or level of development. In other words, you need to design activities to match the developmental stages of the children in your playgroup.

Some examples of small interventions are:

- A daydreamer might find verbal instructions difficult to remember in sequence so the practitioner encourages this child to repeat the instructions to her and corrects or affirms them

- A short-sighted child could be placed near the front of the group for any poster or board activity

- A hearing-impaired child could be placed close to the source during verbal instructions or storytime.

Bigger interventions include:

- Traumatised children need special attention. The abused child can probably cope better with reality through a puppet show, or by using a doll in "play" to express and, through a process, to overcome emotional trauma

- "At risk" children are broadly identified as those who, whilst currently happy and integrated into the school life, come from a family or neighbourhood where there are inherent risks e.g. a family history of mental illness, alcohol abuse, or a community where drug abuse is rife. These children are subjected to influences that are difficult to avoid. "At risk" children include those whose parents are separated or getting divorced, or where the child is in the "care" of a poor and/or sick caregiver who is unable to attend to their needs, where no constructive activity is available and where opportunities for positive interdependence with others are minimal. Children in this broad category cannot depend on parental or community support, and will need special attention at the ECD centre e.g. with regard to washing of body and/or clothes, food to start the day, rest or sleep

- Another possible barrier to learning could be that the language of teaching and learning could differ from the children’s home language.

Ironically the Special Needs Education White Paper 6 identifies the learning programme as the most noticeable barrier to learning. You as the ECD learner-practitioner should remember this when you develop your Learning Programme. You will have to use your analysis of the children in your group to choose appropriate:

- learning/play activities

- methods of facilitating learning

- learning processes

- resources for the age or developmental levels

- assessment methods – and then have the ability to apply the Learning Programme flexibly

Questions you can ask to let developmental stages and needs to inform your analysis:

- What age are my learners?

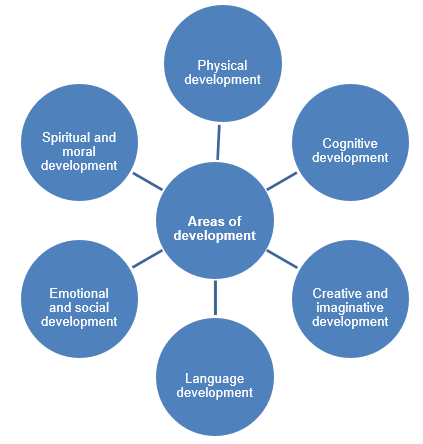

- What are the developmental milestones for this age group in the different domains of development i.e. physical, cognitive and language, socio-emotional, creative and imaginative, moral and spiritual?

- What do key child development theorists like Erickson say about children at this stage?

Activity outcomes

“Play is a key to every child’s well-being. Children learn about the world and experience life through play. One definition of play is “the spontaneous activity of children.†Through play, children practise the roles they will play later in life. Play has many functions. It increases peer relationships, releases tensions, advances intellectual development, increases exploration, and increases chances of children speaking and interacting with each other.â€â€“ Mary F. Longo

Developmental outcomes

Suitably planned learning activities that support the developmental needs and abilities of the group will have a stronger chance of succeeding. This is because children will be working at a level that they can cope with and thus have confidence in them and will learn more readily.

You should cover all of the following areas on a daily or weekly basis to ensure that holistic development is taking place.

The

main domains of development:

You need to plan properly to ensure that you cover the complete spectrum within the developmental age and stage of the children in the group.

For instance:

- Most of the development needed during the baby stage is physical. You will need to provide opportunities to be on the floor so that they have a chance to roll and crawl. Babies that are carried around all day or left in a cot will not develop appropriate skills

- Young children also need physical stimulation but this involves more challenging equipment such as obstacle courses, jungle gyms, music and movement sessions. If you do not expose a child to galloping in time to music, they will not easily learn the skill.

a.

Activity purposes

The developmental outcomes can be

further broken down into goals for each particular activity that you present or

provide in the class:

- Physical development includes fine motor, gross motor, balance and rhythm

- Cognitive development includes concept development, thinking, reasoning, problem solving, counting, and predicting as well as emergent literacy and numeracy skills

- Language development includes vocabulary building through listening and speaking and non-verbal language such as gestures

- Social and emotional development includes self-concept and identity, independence, affection, dealing with conflict, pro-social behaviour, accepting authority and empathy

- Creative and imaginative development includes imaginative play skills, expressing ideas, curiosity and a desire for knowledge

- Moral development includes values such as sharing, kindness, knowing right from wrong, acceptance of discipline and rules.

These goals are often integrated as they cannot be separated and are closely linked and related. One activity may cover many of the goals above – either on purpose or accidentally.

You may set up an art activity that focuses on drawing with crayons. This most obviously covers fine motor and creative skills. However, as the children are engaged in the activity:

- They discuss the colours they are using

- They take turns to use the favourite red crayon

- They talk about what they are drawing.

The activity will thus cover cognitive, language, social and emotional as well as imaginative development.

Think about how an activity, such as drawing with crayons, can stimulate more than one area of development.

1.2.2 Policies impacting on Early Childhood Development

As an ECD practitioner you have to do more than keep in touch with the national curriculum. You owe it to the children at your centre and to yourself to make time in your busy schedule to stay informed of all the things related to early childhood development.

A good idea is to have monthly or quarterly meetings with the other ECD staff where you spend time reading and talking about existing and new ECD related policies, news, and trends.

Aligning

your programme with the national education policy

Remember, you cannot plan your own learning programme in

isolation. You need to do so within the context of the national school

curriculum. A national education policy is never fixed and absolute. So (if you

have not yet done so,) you will need to contact the National Education

Department for the most up-to-date educational guidelines. You will then use

these guidelines to help you plan your learning programme.

Key

considerations

The interim policy for Early Childhood Development includes

five key considerations in planning for ECD policy, namely:

- Correcting past imbalances

- The need to provide equal opportunities

- Issues of scale

- Affordability

- Increasing public awareness and advocacy.

Policy

pillars

The interim policy also sets out the seven policy pillars

of government’s ECD policy:

- A policy for ECD provision

- A policy for ECD curriculum

- A policy on accreditation

- A policy on training in ECD

- A policy on the employment of ECD practitioners

- A policy on the funding of ECD services

- A policy in respect of policy development structures

ECD guidelines provided by the White

Paper on Education and Training

The White Paper sets out the Government’s commitment to the

provisioning of Early Childhood Development and provides a broad policy

framework for the involvement of the Department in ECD.

The White Paper acknowledges that a child’s development and growth is affected by a combination of a number of inter-related factors that constitute the overall environment.

The

Revised National Curriculum Statement for Grade R

This Curriculum Statement outlines the learning outcomes

for Literacy, Numeracy and Life Skills at Grade R level. In other words, it

outlines what learners should be able to do by end of Grade R in each of those

areas.

As an ECD practitioner, you may use these learning outcomes as a guideline. You may adapt them to create learning outcomes that are developmentally appropriate for your learning programme.

National Education Policies

You will find these in the Department of Education website.

An interim policy for early childhood development was created in 1997 and can

be downloaded from their policies page.

Support material and documented socio-economic trends:

You will find support material on the South African Council

for Educators (SACE) website. SACE aims to enhance the status of the teaching

profession, and to promote the development of educators and their professional

conduct. Its website includes information on how to become a registered ECD

practitioner as well as sections on News and Events, Legal Affairs and Ethics,

Professional Development, Publications and other links and information.

You will find support material on the South African Council

for Educators (SACE) website. SACE aims to enhance the status of the teaching

profession, and to promote the development of educators and their professional

conduct. Its website includes information on how to become a registered ECD

practitioner as well as sections on News and Events, Legal Affairs and Ethics,

Professional Development, Publications and other links and information.

Below is a direct extract from UNICEFâ€s WEBSITE.

|

In South Africa, children from birth to four years old, some 4,45 million of them according to the latest census data, represent almost 10% of the country’s total population. Three of the four provinces - KwaZulu Natal, Gauteng, Eastern Cape and Limpopo, where UNICEF focuses its Early Childhood Development (ECD) programme are among those with the highest number of children in this age group. The lives of children in these provinces, especially in the deep rural areas, are directly affected by HIV and AIDS, unemployment and grinding poverty. UNICEF is supporting the development of a National Integrated Strategy for Early Childhood Development and to increase national, provincial and local understanding of IECD in a practical and accessible manner. Special focus is being given to the development of materials for primary care-givers focused on the psycho-social support of 0-3-year-old children and to promoting skills development at community level for these groups, particularly child-headed households. Inter-sectoral collaboration values the contribution and role that different service providers play in ensuring the well-being of children. An approach that is holistic places the child at the centre of a protective and enabling environment that brings together the elements needed for the full development of that child. Parents, or primary caregivers and the family, need access to basic social services such as primary health care, adequate nutrition, safe water, basic sanitation, birth registration, protection from abuse and violence, psychosocial support and early childhood care. One of the main policy documents impacting on early childhood development is the Ministry for Social Development’s White Paper on Social Welfare. This guides the ministry in terms of service provisions in the social development sector. Key points include:

Access to social grants is the key to life-saving support for many young children and their families. In addition, the Child Care Act 1983, as amended, provides for the regulation of early childhood facilities for children and the payment of subsidies/grants to early childhood facilities. These provisions are being reviewed within the new Children’s Bill that is being developed under the auspices of the Department of Social Development. The Department is the main body responsible for the payment of the child support grant for young children in situations of extreme poverty. It is also assigned a key role in the care and support to orphans and vulnerable children in terms of the National Integrated Plan for Children affected and infected by HIV/AIDS. Another important policy document, the Child Care Act 1983, as amended, provides for the regulation of the country’s day care facilities for children and the payment of subsidies or grants to day care facilities. These provisions are being reviewed within the new Children’s Bill currently before Parliament. Within this policy environment UNICEF South Africa is working to strengthen and formalise relationships with key government stakeholders such as the Department of Social Development to ensure that access to the Government’s child support grants for children in situations of extreme poverty; and with other government and civil society partners to ensure that the health, education, water and sanitation, social services and protection needs and the well-being of very young children are met. |

1.3 Ensure that the analysis identifies the key factors that could have an impact on the programme

Your analysis should identify all key factors that impact on your ECD programme, such as:

- The Early Childhood Development setting

- The environment

- The broad needs of the child/children

There are of course many factors that you can include. Let’s start by looking at seven basic key factors that should always be included.

Seven

key ECD programme factors

The American National Association for the Education of

Young Children uses the following seven factors to judge the quality of ECD

centres:

I. Staff child ratio

II. Group size

III. ECD practitioner qualification

IV. ECD practitioner stability and continuity

V. Space and facilities

VI. The needs of the parents community

VII. Multilingual and multicultural needs.

These factors will be discussed in more detail in section 1.5, but we can note that they are related to the Early Childhood Development setting, the environment and the broad needs of the child/children, which we will now discuss.

1.3.1 How the environment impacts on child development

As we already mentioned earlier in this module, the ECD environment can be defined as all the indoor and outdoor space in which the children move and interact at the centre. The physical environment in which the children spend many hours each day has an important bearing on what the ECD experience means to them. The physical environment can influence the children’s behaviour. A cheerful, challenging, stimulating and secure environment will help to meet a variety of the child’s needs. When space is more limited, children become easily frustrated and often more aggressive and destructive.

Having an outside area to play in will greatly contribute to the children’s physical development. If you do have an outside area, make sure that it is safe and preferably fenced in. If you cannot provide a permanent outdoor play area, think of ways you can compensate for this i.e. walking to a park or creating an outdoor area i.e. space to move and feel physically challenged indoors.

The

play environment

Indoor and outdoor environment should be designed to

encourage play. You can achieve this partly by making sure that there is plenty

of equipment that children can integrate into their play. This equipment

includes realistic props such as pots, pans and tools, and other more versatile

items such as blocks, old bed sheets and boards. Make sure there is a variety

of equipment from time to time so that the children do not get bored. For

example, you can move farm animals and small cars and trucks into the block

area or sand box, or introduce new items such as cleaning equipment or tools

into the housekeeping corner.

The

learning environment: resources and physical space

We now look at another important aspect of preparing an ECD

learning programme: the learning environment and the resources needed. As an

ECD practitioner, you should ensure that you have organised your playroom so

that your physical environment matches the way in which you wish to teach. For

example, if you want a flexible, interactive playroom, you need to make sure

that your space, equipment and materials are well organised and attractively

arranged so that children can play in an interactive and flexible way. Let’s

find out how to do this. We will look at the main activity areas, space and

resources.

Space

Whatever the space and facilities available, the activities

in the playroom can be grouped into the following play areas:

- The fantasy area

- The block play area

- The quiet area

- The creative art areas

- The outdoor area

- Other areas

Remember, you need to plan in a creative way to make the most of whatever space is available. Even a small playroom can offer learners many exciting opportunities and activities. Children’s play is how they work at learning (at grassroots level).

As an ECD practitioner, you should be well organised and plan ahead. Such planning satisfies a child’s need for security. The available space should have separate play areas for different kinds of activities. For example, if all construction materials are kept in the same area of the room, the children will be able to find them more easily. They will soon learn that when they want to build, they need to go to the construction area. They will also learn that the construction materials have to be sorted into the right containers and placed back on the shelf after play.

Accommodating

special needs

If you have children with special needs in your class, they

should be comfortable and be able to move around freely. This is particularly

relevant to children with physical disabilities who rely on crutches or

wheelchairs for mobility.

You can assist the children by making sure that:

- Ramps are available to enter the indoor area so that the child has access to the outdoor area

- Pathways are wide enough outdoors for a wheelchair to be pushed on them

- Toilet doors are wide enough to allow wheelchair access and there are bars on the walls of the toilet for them to hold onto

- There are "pathways"“ in the class for the children to move without bumping into furniture

- Resources and equipment are stored at a height that they can access so they are not dependent in all situations

- Resources are adapted where necessary to accommodate their needs.

You will need to be very sensitive to the physical needs of all children with special needs so that the environment does not further compromise their learning opportunities.

1.3.2 Cultural and traditional experiences of development

When choosing resources we need to think carefully of the images and ideas that we are exposing the children to. Research has shown that children develop attitudes to colour and gender very early in life: by the age of two they notice skin colour and between the ages of three and at the age of five they attach values to it – values such as that you are a more capable and powerful person if you have a white skin.

What do we mean by anti-bias?

A bias is the same as a prejudice – it is a

judgement about people based on a pre-conceived belief about the group that

they belong to and not on fact or on who they are as individuals. A bias means

that your expectations of people are defined by their race, culture, religion,

gender or disabilities.

A bias is the same as a prejudice – it is a

judgement about people based on a pre-conceived belief about the group that

they belong to and not on fact or on who they are as individuals. A bias means

that your expectations of people are defined by their race, culture, religion,

gender or disabilities.

The first and strongest influence on children is their parents. They are also influenced by the many messages around them – at the ECD centre, from friends, from television, from advertising, in books and in comics. Children copy the behaviour they see around them. If adults think that different roles and behaviours are suitable for boys and for girls, then children will also believe so. If adults believe that some cultures are superior and others are inferior, this message will be passed on to their children. ECD practitioners have a large influence on children in their class as they are role models and the children spend many waking hours in their company.

ECD practitioners thus have a responsibility to ensure that the resources used in their classes do not reflect bias but show images of, for example, female doctors who are black or stay-at-home dads. What children do not see is just as important as what they do see; if they don’t see disabled people or black people in successful roles that will influence their expectations of people in those groups.

What

is culture fair?

It is very likely that the ECD centre where

you work will include children from several different cultural backgrounds.

Being “culture fair†means recognising, respecting and affirming all the children’s

different cultural backgrounds. Different cultures vary in some important areas

of life:

- The size and structure of the family

- Language

- Food and the way of eating

- Dress

- Discipline

- Customs and traditions

- Religion.

Children often tease others about differences such as language. They need to be taught by your example to understand and value cultural differences.

Simple ways to do this would include providing books on various cultures, celebrating festivals from all the different cultures of the children in your class. You may ask the parents of the children to assist by helping you understand and plan for these celebrations. They could provide appropriate food or clothing, candelabras, etc., that can be used in your classroom. A parent could visit your class dressed in traditional attire and explain the meaning of the festival. “Make and bake†activities could focus on the different foods.

In pictures, books and games, it is important to have positive visual images of the groups that make up society. Whatever their characteristics or background, children should see positive images of themselves in the resources. An excellent example is the pack of “Happy Families†playing cards from ELRU, which show many different types of families.

When making resources such as jigsaw puzzles, card games, matching games, etc, you should make sure that the pictures you use reflect the children in all their diversity. Include pictures of cultures from all over the world, particularly with children over four years of age, as they are ready to learn about the diverse world:

- In the book corner, children need images they can relate to. Photographs of the children themselves are a very useful resource and give them an enormous sense of affirmation

- Create books using photos you take of them, for example about an outing

- Parents can write captions in languages other than English for homemade books and displays

- In art, mix paints in all the different skin tones so that the children can produce a representation of themselves or others

- In the imaginative play corner, reflect a variety of cultures in the dressing up materials, play foods, props and in the dolls.

Learning

resources to encourage a gender-fair environment

If adults classify toys along gender lines,

children will too. In a research study, a group of psychology students were

asked to examine a list of 50 toys, and to mark which ones were appropriate for

boys, which were appropriate for girls, and which were appropriate for both.

The results were that 24 toys were marked for boys only and 17 for girls only.

The boys†toys included guns, doctor sets, tricycles, remote control cars,

microscopes and blocks. The girls†toys included teddy bears, phones, dolls and

dollhouses. The study then analysed the kinds of development promoted by these

toys.

The boys†toys encouraged being social, constructive, aggressive and competitive, while the girls†toys promoted being nurturing (caring) and creative. This research shows that different toys promote different skills, and so have a profound effect on a child’s development.

Support a non-sexist viewpoint in your

playroom – especially in areas that are traditionally for girls (like the home

corner) or for boys (like science or construction activities). Boys and girls

should have equal access to all experiences and should be encouraged to try out

the various activities.

Support a non-sexist viewpoint in your

playroom – especially in areas that are traditionally for girls (like the home

corner) or for boys (like science or construction activities). Boys and girls

should have equal access to all experiences and should be encouraged to try out

the various activities.

Be conscious of the messages that are given out by the children’s books. Is there a fair distribution of stories that are centred around boy and girl characters? What sort of activities are men and women shown to be doing? If most of your books show only the traditional roles, then look for books in the library that show girls and boys, men and women, who are breaking the stereotypes.

Create your own books as well as posters, games, cards and puzzles that use images showing both sexes in a wide range of roles, for example, a father staying home to care for the children or a woman police officer.

Learning

resources to encourage a disability fair environment

Children with disabilities have the same need as the

others to see themselves reflected in their school environment. They need to be

surrounded by positive role models and to have a positive view of themselves.

It is also important for other children to see images and hear stories about

disabled people so that they understand and accept them.

Try to find books that show people with

disabilities in active roles. Are there any books in your library that have a

disabled person as the main character? Look for stories that have characters

who are disabled but their disability is not the main focus of the story. (An

example is Vusirala the Giant, a

South African story in which the little girl who defeats the giant walks with

crutches.) Again, create your own books using photographs of all the children

in the class.

Try to find books that show people with

disabilities in active roles. Are there any books in your library that have a

disabled person as the main character? Look for stories that have characters

who are disabled but their disability is not the main focus of the story. (An

example is Vusirala the Giant, a

South African story in which the little girl who defeats the giant walks with

crutches.) Again, create your own books using photographs of all the children

in the class.

If you have hearing-impaired children try and provide many stories on tape for them to listen to. For visually impaired children make tactile “touch me†books with textured pictures.

Display pictures of children with different disabilities. Include pictures of them interacting with others who are not disabled. Look for pictures of disabled adults in a variety of roles, as parents, sportspeople, teachers, etc. When you make dolls and puppets for imaginative play, you could add some characters wearing glasses, or a hearing aid, or in a little wheelchair.

Make posters with words like “helloâ€, “I love youâ€, “happy†and “sad†in different languages, and include sign language and Braille.

Are

resources suitable within the community context?

According to didactic or teaching principles,

we work from the known to unknown or familiar to unfamiliar. This can also be

applied to resources.

Many of the books, games and puzzles that are produced overseas contain images that are not familiar to many children within a South African context. A typical example is of Christmas being depicted with snow – for our country this is not a reality. As ECD practitioners, we need to be aware of our community context and provide the children in our class with more familiar images. This does not mean that we cannot expose them to snow for instance, but we need to look at their age and developmental stage and interests to ensure that we are not confusing them.

There are many resources that can be bought that are made in South Africa and have images that are more familiar to our children. (A list of these resources has been included at the end of this Unit Standard for your convenience.)

You will still need to use your discretion and common sense and understand the context of the children in your group. For example, children living in a township will have a different understanding to those living in leafy suburbs nearby.

Some

suitable children’s books

The following books are all published by the

Anti-Bias Project of the Early Learning Resource Unit and are available to

purchase from ELRU directly. They are well illustrated and include colour photographs:

- Anjtie – Xhosa, English, Tswana and Afrikaans book – about a girl who lives in Genadendal and what she gets up to, including driving a donkey cart

- Nkqo! Nkqo! – Xhosa, English, Tswana and Afrikaans book – various families of different cultures are captured in daily rituals

- They were wrong! – about the prejudices that exist regarding various cultures in Cape Town

- At School, What if…? – about Ncebakazi who uses a crutch and the fears she has of going to a mainstream school for the first time

- Mhlanguli – Xhosa, English, Tswana and Afrikaans book – about a boy who lives in Khayelitsha and does ballroom dancing as a hobby.

How to

design bias-free activities

When you were preparing learning resources,

you looked at how to make those resources free from cultural, racial and

gender-based bias. The same criterion applies to designing activities. The

activities you design must be bias-free. This means that the activities must

not reinforce biased ideas about different people in the world around us.

Remember that when we are biased, we have a fixed opinion that is not based on fact.

A bias is a belief, often based on erroneous information that can lead to the

unjust, unkind, or unfair treatment of others. Some of the most common forms of

bias and discrimination are racism, sexism and stereotyping. Let’s look at each

of these in turn.

- Racism dismisses whole groups of people as inferior because of skin colour, race, religion, or national origin, claiming that such characteristics determine a person’s abilities and behaviour (Cronbach, 1977)

- Sexism is the discrimination against someone on the basis of their sex (or gender). Societies assign different roles to people based on their gender. The nature of the diverse roles that male and female children play in our society unfolds at a very early age. For example, toys for boys often include action figures, such as toy soldiers, while toys for girls are typically those that require nurturing and caring, such as dolls

- Stereotypes simplify the way we view the behaviour of a certain race, or gender, or culture or people who are physically challenged. Stereotypes give the impression that all people who share a particular characteristic will behave in a certain similar manner. The truth, however, is that not all Italians like pasta and not all black people can sing and dance well. It is only the common generalisations (stereotypes) that would have us believe this.

The activities you design for your playgroup should not only be free of bias such as racism, sexism and stereotyping; they should also celebrate diversity. When you design activities that are free of bias you are helping children to celebrate their diversity in various ways:

- A bias-free activity can portray differences positively. An understanding of differences and accepting those differences, helps to encourage respect

- A bias-free activity can stress similarities. When people discover that they are all just people, like everyone else, co-operation becomes possible

- A bias-free activity can examine attitudes and values, thereby drawing attention to bias and at the same time trying to reduce it

- A bias-free activity can develop the skills and capabilities that the children need to realise their potential in our complex society.

Usually, children who are exposed to bias-free activities that celebrate diversity will positively respond to individual differences. Understanding, respect and positive interactions form the cornerstone of bias-free activities that celebrate diversity.

As our society changes, so the make-up of our playgroups changes too. More and more playschools have a diverse child population with a variety of races, religions, and language groups. In addition, more and more playrooms include children with special needs (due to learning difficulties or physical limitations). It’s important that you as the practitioner are aware of any bias in children and deal with it effectively. If you work closely with the babies, toddlers or young children in your care, you will be able to notice and deal with inappropriate behaviour more easily. If you do find some biases, you need to spend time with the children, openly discussing these feelings and beliefs. Ask yourself questions like: Is the bias a result of misunderstandings or misconceptions? Can you counsel the biased child effectively? You must constantly be aware of the need to be an appropriate role model. Nothing less than the fair, consistent, caring treatment of all children is acceptable.

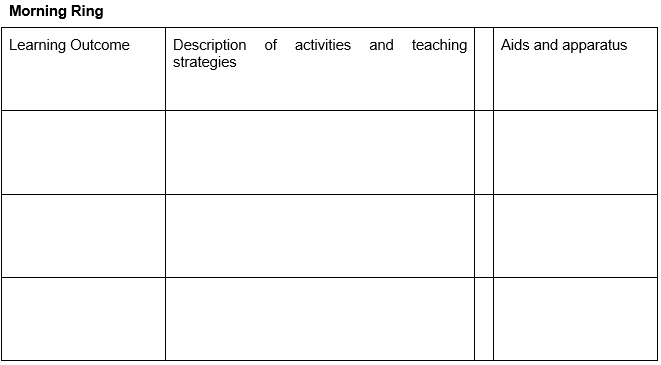

Providing a variety of bias-free activities is a good way to challenge bias and discriminating behaviour. One good place to deal with bias is in the morning greeting ring. The morning ring provides time for children to get to know one another. For example, you can provide opportunities for the children to discuss their backgrounds, families and where they live. This allows you to explore diversity within the context of each child’s own family life. By doing so, you do not portray all members of a particular race, gender or culture as living in the same way. You should start these conversations. You can assist and support those children who may feel uncomfortable by sharing their information in a large group. Some of the topics you can raise for discussion include:

- Family lifestyles – What occupations do members of the family have? What hobbies do family members have? Who are the various members of each child’s family? What are the extended family ties?

- Family traditions – What holidays are celebrated? What foods are typically served? Who joins the family for celebrations? What religion is observed (if any)?

- The home – What is the child’s house like? Where do they live? Who lives there with them?

- Gender role in the family - Are children of both sexes disciplined in the same manner? Do children of both sexes participate in a variety of extra-curricular activities? For example, do boys and girls do ballet and practise their ball skills? Are boys rewarded for being aggressive, and girls rewarded for being placid? Are girls encouraged to consider the same career options as boys?

Let’s look at some other bias-free activities

that you can use:

Let’s look at some other bias-free activities

that you can use:

- Activities for reducing bias against children with special needs

- Gender identity and gender role activities

- Roleplaying activities

- Critical thinking activities

- Group action activities

- Reading activities.

Let’s look at each kind of activity in more detail.

a) Activities for reducing

bias against children with special needs

Children with special needs may be different

from other children in either a negative or positive sense. Sometimes they are

physically challenged in some way, and sometimes they are so gifted or talented

that it sets them apart from the others just as much as a physical or mental difference

does. Children with special needs may have fears or problems that form the

basis of, or are the result from their uniqueness. You need to design

activities to help both children with special needs and the other children in

the class to accept each child as a valuable member of the group.

You may for example design activities where children change places with different classmates; for example, sighted children may wear blindfolds for a while in order to better understand the world of the child who cannot see well. Similarly, physically mobile children may spend time trying to manoeuvre a wheelchair. This will give them an idea of the frustration and misery that people in wheelchairs have to deal with.

Another activity is to make a wall display of photographs that challenge stereotyping. For example, use photographs of amputees (people who have lost an arm or a leg) on skis and basketball players in wheelchairs. Discuss the photographs with the children in your playgroup and introduce the concept of people being "differently-abled" rather than disabled.

b) Gender identity and gender

role activities

Gender identity and gender roles are areas

where stereotyping is so common and so widely accepted that the stereotypes go

unrecognised and are not even criticised in the playroom and outside it. For

example, in many playrooms, girls still are assigned the cleaning up tasks,

while boys get the chores that require skill or muscle. You as the ECD

practitioner assign tasks, and you should be very aware of the effects of

delegating such tasks in stereotyped ways.

Children should receive plenty opportunities to explore their male and female roles. You can make the children aware of what society expects of them and encourage them to think critically about these “given†roles. Discussions could include how males view their roles in the playroom and in society, or how females see their changing role. These are big issues, but you could touch on them subtly with simple examples. The question of how gender obstructs or facilitates success can be addressed. If gender is seen to be a barrier, how can you correct such a perception? A good activity is to invite visitors who will challenge conventional thinking to give talks in your playroom, for example a male nurse, a female police officer or a black female doctor.

c) Roleplaying activities

Children like to tease each other. Children

who refer to classmates who wear glasses as “four eyes†are cruelly insensitive

to their friends†feelings. You cannot and should not ignore such behaviour. If

you do, you encourage the children who are name-callers and labellers to think

that you accept the statements and related actions as truths. Your children

need opportunities to examine the circumstances that lead to such hurtful

behaviour, and they need also to be challenged to rethink both their attitudes

and their actions.

In the dress-up corner or make-believe area, you may provide opportunities for children to role play biased behaviour. These activities are intended to evaluate the injustice, and to suggest strategies for change. You could set up scenarios for children that allow girls and boys to try roles usually considered "male" or "female".

d) Critical thinking

activities

Children can probably point out biases that they

find in magazines, see on television, or recognise in playroom materials. A

bias can be something like society’s idea of what the perfect female body

should look like. Think of all the models in women’s magazines. You could have

the children page through such magazines and discuss what they see, and assess

the images that are presented to them.

Certain dolls found in some playrooms have come under criticism because they reinforce a stereotyped image of all women being "thin, curvy and sexy". Some experts believe that dolls like these reinforce a picture of an idealised or perfect body that children, especially in their adolescence, will aspire towards. A bias-free approach does not mean that you need to throw out your doll collection. Instead, you can encourage children to talk about what they think, feel and understand. Say, "Here’s a woman doll. Do all women look like this doll? No? That’s because women in lots of different shapes and sizes and colours. If you were going to make a “mommy†doll, what would your doll look like? If you were going to make a granny doll, what would your doll look like?"

e) Group action activities

The process of seeking out, defining and

examining playschool bias that is related to race, gender, culture and special

needs is just the first step in dealing with these issues. Actually, planning

to make the necessary changes when inconsistencies and biases are uncovered is

the hard part. Derman-Sparks (1989) tells the story of a preschool class in

which there was a wheelchair-bound child. After the child was enrolled, the

group began to consider the special needs of their playmate.

By talking with the practitioners, parents, school directors, and other significant people, the children discovered that there were no parking spaces for children with disabilities in the preschool’s parking lot. The pre-schoolers were not satisfied with simply noting this oversight; armed with buckets of paint, they painted the necessary lines themselves! On top of that, they asked their ECD practitioner to help them make notes to be left on the windshields of cars informing the motorists that these parking spots were reserved for children with disabilities. Obviously, young children cannot and do not embark on projects like this on their own. The teaching staff must serve as catalysts for putting such ideas into action. You as practitioner can arrange for representatives of a variety of interest groups to visit the playroom and address the children. Individuals from various religious organisations, ethnic groups, and social service organisations could come to discuss needs in the community that require that some type of action is taken to meet a desired goal. Children may be encouraged to volunteer time, participate in drawing pictures, make posters, or take part in similar activities, with the objective of working co-operatively to achieve a common goal.

f) Reading activities

Reading books is an activity that can be used

to identify bias and counter it, or to reinforce and celebrate anti-bias and

diversity. For example, you could look at books for discriminatory portrayals

of men and women in the words of the story or the pictures. Or you could read

stories that portray men and women in a variety of different roles, such as

books on cowgirls, or pictures of men caring for babies.