Unit 3 Online Study Guide

Learning Unit 3: Prepare an ECD programme

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to prepare an ECD programme. You will be able to:

- Ensure that the programme sufficiently addresses the developmental stages and particular needs of the children as revealed by the analysis

- Ensure that the programme provides flexible options for implementation

- Ensure that the programme specifies the sequence, timing and main resource requirements of the planned activities, including opportunities for assessment

- Ensure that the programme provides a balance of developmentally appropriate activities to support the development of all the children

- Ensure that the programme provides a balance between indoor and outdoor activities and individual, small and large group activities to support the development of the children. Ensure that the balance between such activities, particularly between individual and group activities is appropriate to the developmental stages of the children

- Ensure that the programme can be implemented in the given context and within available resources

- Ensure that the programme complies with relevant national policies and guidelines

- Develop learning programmes to enhance participation of learners with special needs.

Prepare an ECD programme

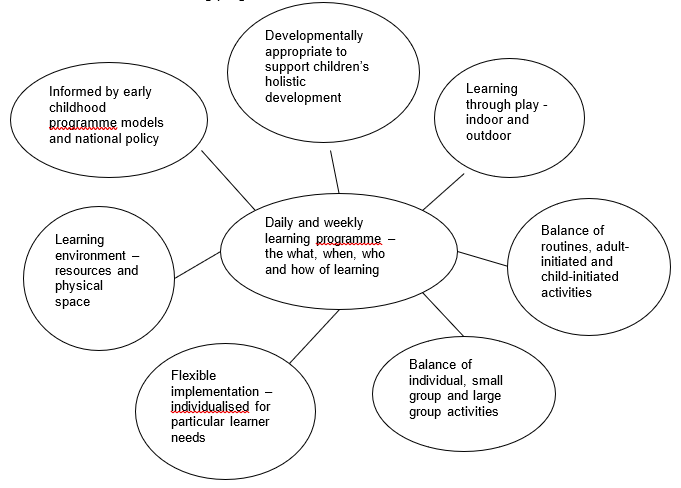

Careful consideration and planning are necessary when you prepare a learning programme for your ECD centre. You should think about the learning activities and experience that you should provide for children daily, weekly and in the longer term. You should also think about the children’s interests and developmental needs. The mind map below provides an overview of the key elements in the ECD learning programme.

In this module, we will examine these different elements to equip you to prepare your own ECD learning programme, with the assistance of your mentor. You may find it helpful to think of each element as a different coloured filter. When the ECD practitioner designs the ECD learning programme, she focuses on each element, placing one coloured filter on top of the other. In this way, she builds up the learning programme until all the colours are represented and the learning programme comes to life – in full technicolor.

Designing a learning programme

There are many issues that you should take into account when you design an ECD programme. Below are some pointers:

- Young children learn best through active, engaged, meaningful learning.

- Young children learn best in an early childhood programme that is developmentally appropriate.

- Young children learn best in an early childhood environment that is appropriate for their age and stage of development.

- Young children benefit from a consistent routine or daily schedule in the early childhood classroom.

- Young children learn best when the school develops a sense of community for all participants.

- Young children function best in early childhood programmes that value and reinforce continuity.

- Young children benefit from early childhood programs that provide a careful transition from preschool to kindergarten and from kindergarten to the primary grades.

- Young children learn best when they are with teachers who consider them and respond to them as individuals.

Using these principles as a foundation, we can say that planning and organising for an effective early childhood programme should emphasise five factors: quality staff, suitable environment, appropriate grouping, consistent schedules, and parent involvement.

Routines change according to the age of the children. This means that adults who plan a daily routine should think about the needs of the children they are working with.

For extra information on the principles of designing a programme and ideas, see the handouts called NELDS and “Creative Ideasâ€.

Adapting learning activities is not as difficult as it may seem. There are some guiding principles you should apply, but the most important elements are to:

- Be willing to adapt activities so that children with special needs can be fully part of the class

- Be open to learning, experimentation and ideas from other sources

- Develop a sound knowledge of the child’s strengths and weaknesses.

Differentiating

activities into level of more and less difficulty

All children learn

different concepts and skills at different rates. Thus, all activities should involve

levels of differentiation so that stronger learners are encouraged to push

themselves, and weaker learners are still able to achieve what they need to.

Let’s look at a practical example of an art activity:

You have set up an activity, where the learners are going to glue various items onto a piece of cardboard. The sorting tray has buttons, string that is already cut into various lengths, polystyrene bubbles and pieces of fabric. There are also balls of wool, scissors and felt tip pens on the table as well as glue pots.

Children with fine motor skills that are not well developed can simply take items from the tray and paste them onto the cardboard. Those who have stronger fine motor skills will probably choose to cut wool from the balls and may also use the felt tip pens to draw on the cardboard. Thus the activity is differentiated as it makes provision for differing levels of skills.

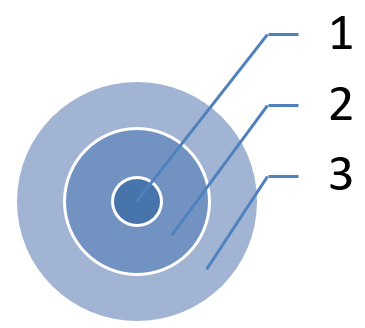

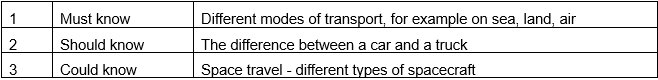

The diagram below explains the concept by using a cognitive example. Using transport theme as an example, there are basic things every child must know about transport. These would fall into the dark central area labelled 1. The larger pale blue area labelled 2 represents things the children should know. The largest and lightest area, labelled 3, represents things the children should know.

The following diagram represents differentiation in levels of knowledge on the theme of transport:

You could start the discussion in the morning ring with the "must know" concepts and then expand these into the "should know" and "could know" areas, but only if the learners were coping and contributing to the discussion. For gifted learners in particular, you would encourage further exploration in the "could know" arena. Remember that gifted children are also classified as learners with special needs.

3.1 Ensure that the programme sufficiently addresses the developmental stages and particular needs of the children as revealed by the analysis

When you analyse the context for your ECD learning programme, your analysis should clearly identify the developmental ages, stages and needs of all the children within the playgroup. This understanding will help you later when you prepare your ECD learning programme. As you know, it is important that the ECD programmes that you prepare for young children are appropriate to their ages and stages of development. This is known as developmentally appropriate practice (DAP).

3.1.1 ECD learning programmes can enhance participation of learners with special needs

ECD learning programmes can enhance (improve) the participation of learners with special needs such as physical, health, cognitive, emotional or economic needs.

For many years, the policy in our education system was to identify learners with special needs and to provide them with specialised education. This system worked well for some learners, but also isolated many others. The services that were provided in specialised education were not equally apportioned according to race, geography or even the type of disability. This means that many children with special needs did not have access to these services. Even worse, terms such as "spastic" or "mental" were often used to refer to them.

The following approaches to education of children with special needs were applied at various times in the past in South Africa:

- Special education

- Mainstreaming

- Integration

Special education

Special education

schools were specifically designed to deal with a particular disability. These

facilities were staffed with people who have trained to deal with particular

disabilities and maximise the learning of the children who were placed there.

In this model, children who were identified as having a special need were only

permitted entry into a "special school"; they were not allowed to

remain in a mainstream school. The approach was very much based on the idea

that if a learner was unable to learn in a mainstream environment then it must

be because there is something "wrong" with that particular learner.

Thus it seemed to make sense to remove them from the mainstream and place them

at an institution where their needs could be met more effectively.

Unfortunately, the special education approach had many flaws. Special education schools often kept learners separated from the rest of society. Excluding these children from mainstream society meant that they were robbed of a chance to interact with other people. This often also meant that they did not receive an opportunity to improve their social skills.

Separating learners with special needs also had an effect on mainstream learners: it encouraged them to view individuals with special needs as "inferior" or "defective".

Mainstreaming

The mainstreaming

approach gave all children the opportunity to attend mainstream schools for as

long as they could keep up with their classmates.

The purpose of mainstreaming was to give learners with special needs a chance to push themselves to the point where they could survive in "mainstream" education. This solved the problem of isolating learners with special needs, because now they were rather given the opportunity to improve, until they could perform at the same level as their "normal" classmates.

The problem with mainstreaming was that it ignored the fact that some children had genuine educational challenges that required support. Mainstreaming expected them to be able to overcome their barriers without any extra help. For example, under the mainstreaming approach, learners who had cerebral palsy would have to try to write at the same speed as their classmates, a task that was simply impossible for them.

Integration

Another attempt to

solve the problem of special needs education was called "integration".

It was similar to mainstreaming because learners with special needs were placed

in mainstream schools. However, unlike in the mainstreaming approach,

integration also provided these learners with specialised attention that was aimed

at helping them to cope with their learning challenges.

Unfortunately the integration approach was also problematic. Whenever learners were taken out of their classes to receive their learner support they missed out on things that their classmates had learned. This had the effect that when the learners with the special needs came back they were even further behind their classmates than when they left.

A second problem with this approach was that many children were stigmatised. They were often subjected to abuse or teasing from their peers.

Inclusive education

Inclusive

education is based on the belief that all learners have a right to be educated

as much as possible in the environment that is the best for them. This approach

differs from other approaches in several ways:

- It emphasises modifying the teaching methods to suit the learner, instead of trying to change the learner so that he or she "fits in".

- There is awareness that all learners have their own strengths and weaknesses, things that help them to succeed and things that prevent them from succeeding.

- An inclusive approach always tries first to help learners to succeed in the mainstream, but if it turns out that mainstream education cannot help them to achieve their full potential, then it makes specialised learning support available to them.

- Lastly, inclusive education calls attention to the fact that almost anything can be a barrier to learning, if it is not managed correctly.

3.1.2 Special needs requiring attention during the development of ECD learning programmes

It is vitally important for you as an ECD practitioner to be aware of the range of special needs that you may come across in your class. While you should be able to identify them, it is not always easy to identify more suitable special needs, such as Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD), which is on the autism spectrum.

As an ECD practitioner you are also not able to diagnose disabilities in children. Only medical practitioners are able to do this. Nevertheless, your observations and reports can influence a diagnosis, and therefore they need to be factual and comprehensive.

When a special need is identified, it often results in a child being labelled as being different or being called a "slow", "poor" or "naughty". This is a discriminatory practice that expects less of the child; the label becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy (the child acts as he or she is expected in terms of the labels).

Special needs children vs children with special needs

a. “We label boxes, not

childrenâ€

We may also fall

into the trap of referring to "special needs children" when we should

say "children with special needs".

b. Stop and consider the

difference

If we say "special

needs children" we place the emphasis on their special needs when in fact

we need to view them as children firstly and only then consider their special

needs.

While it may seem like a very small difference, it can be extremely important when we identify and assist children. We have to remember that they are children who have developmental needs, before we look at how to adapt to their particular and special needs.

Please beware of using expressions such as "children who are ADD" or "children who are HIV"! They may have a disorder or a viral infection, they are not that disorder!

Early

identification of special needs and barriers to learning

As the ECD

practitioner, you are an important link in the early identification of special

needs. While some parents may notice that their child is not meeting

developmental milestones and seek help, others may not notice, or may choose to

ignore the issue.

Many parents compensate (make up) for the child instead of letting them struggle.

The earlier a problem is identified, the sooner the child can receive appropriate support and continue to learn without falling behind developmentally. It is much easier to adapt activities in this formal teaching environment and children are not as aware of the individual attention. It is also important to prevent bad compensatory habits (trying to make up for the problem) from forming such as visually impaired children constantly shaking their heads or poking their eyes.

Special needs may be very obvious: for example, a child starts in your class and you can see that she is wearing splints on her legs. However, another child may start in your class and it takes you a few weeks to notice that he is not coping as well as others with certain activities. How can you be certain that the child has a special need or barrier to learning?

Here are some reasons why it is not always easy to identify special needs in the ECD phase:

- You need to observe carefully and have a sound knowledge of developmental phase

- ECD is informal, so children are not expected to perform at the same level; no formal tests are conducted

- Children avoid activities they find difficult, so you don’t always get to observe the problem area

- Young children are not always consistent on a day-to-day basis

- Some children are late or slow developers.

The Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS) is a good guideline to follow in order to establish if further intervention is necessary.

- Create a learner profile by reading any forms and background information that the parents have provided. Look at the child’s likes and dislikes in the learning programme.

- Identify any special needs or barriers to learning by assessing the child against developmental norms. It is important that you do not just compare that child to the rest of the class, as this may not be a true reflection of age-related ability in a particular area. Think of where and when the child experiences difficulties, and consider whether it could be your teaching style or the environment that may need to be adjusted. Sometimes teachers have unrealistic expectations of children, for example, that a three-year-old should be able to concentrate for a long story that takes 25 minutes to tell.

- Think of ways that you can adapt activities to include the child. (This is covered in depth in Lesson 4.)

- Monitor the child’s progress and evaluate whether your assistance as the teacher is sufficient, or if the child needs to be referred through the SIAS system.

3.2 Ensure that the programme provides flexible options for implementation

Children are encouraged to participate in a variety of activities. However, these activities must be flexible and be adapted to suit the child’s individual needs. The fact that there is a choice suits the attention span of young children: although continuous activity is encouraged, they will not be in any zone long enough to become bored or frustrated. The outdoor play portion allows them to run, jump and let off steam after focused activities.

Within the ECD playroom, each child is viewed as a unique individual with special abilities, interests and learning styles. For this reason, the ECD learning programme needs to be flexible, so that each child can participate in the programme in a way that suits him or her as an individual. This type of programme flexibility is also geared to accommodate learners with special needs.

Here are some signposts of a flexible and individualised learning programme:

- The ECD practitioner takes time to observe children as they play and notes their abilities, strengths and challenges, so that she knows how to adapt the programme to meet their individual needs

- During certain activity periods, children are able to make their own choices about which activities they want to engage in and how to use the resources and materials. This enables children to choose activities that stimulate them and that they enjoy

- The activity zones are stocked with resource material that cater to the children’s different developmental levels. For example: the puzzle corner will offer a range of puzzles from elementary to challenging. In this way, children can make choices that match their developmental ability

- The ECD practitioner takes time to interact with all learners, including those children who are shy, quiet or who make a few demands on her attention

- The learning environment (the physical layout, learning resources and activities) are adapted for children with disabilities or barriers to learning. In this way children with disabilities are included and are able to participate fully

- During free play, the ECD practitioner interacts with individual children or small groups and offers guidance, support and encouragement. Learning activities are also adapted to suit individual children.

3.3 Ensure that the programme specifies the sequence, timing and main resource requirements of the planned activities

Let’s examine the daily or weekly ECD programme in more depth, so that we can understand why it is structured or sequenced in this way. A well-designed learning programme provides a balance of the following types of activities:

- Indoor and outdoor activities

- Individual and small group activities – initiated by either the child or adult

- Large group activities – adult-initiated

- Routine activities

- Effective transitions between activities.

In addition, all activities are developmentally appropriate for the children in the playgroup.

The daily ECD learning programme creates a safe, predictable and carefully designed structure of activities and routines. The ECD practitioner uses the daily programme structure to help her when she prepares her longer weekly learning programme. Usually, the ECD learning is theme-based. Typical themes include: the seasons, the sea, the weather, pets, you and your family, animals, and one world – different people. Once a theme is selected, usually for a week or two-week period, the ECD practitioner identifies and creates learning resources and activities linked to this theme. She fits these into the relevant time slots in the daily programme.

Using themes helps to keep the ECD learning programme fresh and exciting for young children. The ECD practitioner tries to choose themes that are developmentally appropriate and match the children’s interests. For example, if it is the Soccer World Cup, and many children are interested in soccer, she may use the theme sport, so that children can express their enthusiasm and interest. A theme usually runs for a week or a two-week period, and many of the activities and routines in the daily programme are linked to the theme.

Including opportunities for assessment in the programme

Assessment can provide very useful information to parents and educators about how children develop and grow. Using the developmentally appropriate assessment system can provide information to highlight what children know and are able to do.

Assessments of child development are for different reasons, each requiring unique indicators. The various types of assessments include:

- Assessments for an overview of current child status

- Assessments to support learning (e.g. by parent or teacher to see what type of activities the child is ready for; mostly informal)

- Assessments to identify special needs (e.g. growth monitoring to identify malnourished children)

- Assessments for programme evaluation (to determine whether the programme is effective in reaching its goals, or to compare alternative programme models and approaches)

- Assessments to monitor trends (e.g. assess the status of children within or across regions and over time)

- Assessments for high-stake accountability (to hold individual students, teachers or project managers accountable).

The following tools are the norm:

Screening

Developmental

screening is the process of looking at several areas of development on a superficial

level to determine whether a child is developing as expected.

Ongoing assessment

There is a difference

between screening and ongoing assessment. Screening lets the practitioner have

a quick look at development whereas ongoing assessment looks at development

constantly and continually over time. Ongoing assessment is a method that

collects information about a child’s strengths and weaknesses, their levels of

functioning and specific characteristics of their learning or learning style.

Diagnostic assessment

This is a process

that looks at areas of definite concern and could also include a broad range of

development areas. These are typically uniform (identical) for a large number

of children; a score is given that reflects a child’s performance in comparison

to other children of the same age, gender and ethnic origin. The results could identify

an area that needs extra attention or a child being diagnosed correctly.

To ensure that the programme provides a balance of developmentally appropriate activities to support the development of all the children, your programme may include an appropriate mix of:

- Routine activities

- Adult-initiated activities

- Child-initiated activities

To best support children’s holistic development, the ECD daily programme incorporates both inside and outside activities. Usually outside activities are physical and encourage gross motor function. When children climb ropes, peddle tricycles, play on swings, hop, skip, run and jump and so on, they exercise their physical muscles, build fitness, and develop feelings of well-being that accompany physical activity. In a society where children are more sedentary (inactive) through watching television, playing computer games and travelling by car or taxi.

Usually, the ECD practitioner will provide opportunities for outdoor sand and water play (supervised) where learners can measure, pour, build, float and generally exercise their fine motor, creative/imaginative and cognitive skills.

Of course, not all ECD centres have an outdoor play area. In these cases, the ECD practitioner must find opportunities to take children to a nearby park, and offer opportunities for physical movement inside the playroom.

Indoor activities: In the ECD daily programme, there are many opportunities for indoor activities. Usually children participate in rings and use activity zones e.g. creative art area, literacy/reading area, fantasy play area. While movement rings provide opportunities for physical movement gross motor development, generally indoor activities focus on the other developmental domains.

Individual and small group activities – child- or

adult-initiated

In the daily or

weekly programme, we encourage a particular range of children’s social

emotional and language development through offering individual and small group

activities initiated either by the child or the ECD practitioner.

Children need to acquire some independence and the ability to play on their own at times. Also, some children with an introverted (shy) nature actually need lots of time on their own to feel peaceful and happy. Children also need to build relationships with peers and learn to cooperate together during play or an activity. This is where small group activity is important. The free choice activities that form an important part of the ECD Programme allow children to participate on their own or in small groups in a flexible way. For example, a creative art zone will usually group children in fours around a table; however, the reading/puzzle corner allows children to play independently.

In addition, some of the activity zones should provide an activity that has been prepared by the ECD practitioner, e.g. finger painting with autumn colours, or a range of picture books on the theme "the circus". Children can participate in the activity in their own unique way – allowing them to take the initiative in their own learning.

Large group activities – adult-initiated

The most important

adult-initiated activities in the daily programme are rings. Ring times

encourage learners to participate together as a class, developing another range

of social, emotional and language skills. The most important rings are these:

a) morning rings and special rings

b) physical activity rings

c) story rings

a) Morning rings and special

rings

Morning rings

provide an opportunity to gather together as a group and set the "tone"

for the day. Usually the morning ring contains:

- A welcoming or greeting song

- Sharing of news – for example an unusual event like getting a new puppy

- A discussion about the weekly theme (perhaps including show and tell)

- An opportunity to talk about any emotionally difficult event that a child is anxious about (for example bullying, a parent in hospital, an upcoming operation)

- An important event in the community or world (for example the Olympic Games or a village fair).

Special rings are used to mark special events and occasions, such as birthdays, the school’s birthday, or holiday celebrations. The morning ring is often used as the timeslot for the special ring.

When you have a birthday ring, the birthday girl or boy is the centre of attention. You could place a crown on the birthday child’s head and refer to him or her as prince or princess for the day. You could let the birthday child choose the creative activity for the day.

If appropriate, parents or caregivers could be asked to supply some refreshments (cake or biscuits) for snack time. You may even invite them to join the birthday ring if you wish. This helps to make the day special for the child, and a celebration to remember. You could present the child with a birthday book containing one picture that was drawn by each member of the group. All this boosts the child’s self-esteem.

b) Physical activity rings

Physical activity

rings are designed to get children moving. These rings usually involve games,

music and poetry or rhymes.

Let’s look in turn at:

- Movement activities

- Musical activities

- Poetry and rhyme activities

Movement activities

Movement

activities involve both physical activity and memory. The children are given

instructions. They need to look, listen and do the actions. (You or a child can

demonstrate.) The older the children are the more complex and lengthy the

movement routines will be.

These activities should include both small muscle development (moving fingers and toes) and large muscle development (moving arms, legs, head and body). Large muscle activities include movements that exercise balance – on a low beam, or standing on one leg, or balancing a bean bag on the head, or a combination of these.

Make sure that the children take off big jackets and jerseys. Set an example by doing the same. There should be an introduction to the ring, for example an action rhyme or game, which serves as a warm-up for the ring. Plan one main activity and three sub-activities to avoid children having to wait in long rows for their turn. Always allow for a relaxation period after the physical activity.

Remember to praise children for their efforts in order to encourage and support them.

You could also use any of the following for smaller groups:

- Skittles: children roll a tennis ball and knock over as many skittles as they can

- Hula hoops: children use any part of their body to hula

- Bean bags: children throw bean bags into boxes, which are placed one behind each other; children try to throw bean bags into the furthest box.

Musical activities

Music is a source

of great enjoyment for children and also serves a very important purpose.

Children learn musical concepts, such as soft and loud sounds, high and low

notes, and fast and slow tunes.

Musical activities provide an excellent opportunity for children with poor co-ordination to gain confidence with physical activity through dancing, imitating and moving to specified musical cues. You could ask them to jump up and down for high notes, crawl on the ground for low notes, hop or skip to specific beats, and so on.

Make sure you choose musical instruments and songs that reflect the languages and cultures of all the children in your playgroup, and if possible of all the people in South Africa.

Poetry and rhyme activities

Young children

greatly enjoy the repetition and rhyming of poetry and the different kinds of

rhymes.

Finger rhymes and action rhymes are good for fine motor development. The children find them challenging and fun.

Always make sure that you choose a variety of poems and rhymes that reflect all the languages and cultures of children in the group. See the box below for examples.

c) Story rings

Story rings are

usually scheduled at the end of the day. The children sit in a semicircle with

the practitioner sitting up front. Encourage the children to sit with their

legs folded and have their hands free. Ensure that they leave learning

resources, blocks, dolls, and other equipment behind.

Children who have hearing problems or tunnel vision should sit opposite you (or opposite the person who is telling the story).

Set a good pace for the story, projecting your voice well and use varied intonation (your tone of voice must vary, and go up and down). Show pictures and illustrations, and only use the book where necessary. You could also use story tapes or CDs.

There is a special magic about the art of storytelling – telling children the story in your own way, rather than always reading from the book. Try to learn the techniques of the good storyteller. Your local library should have books to help you. Or find out if there is a good storyteller in your community who could occasionally tell a story during story ring.

Story props or visual aids always help to make the story more exciting and stimulate the child’s imagination. These could be in the form of puppets, pictures, and flannel boards, moveable characters or doll and role play. Make sure your story props are culture-fair and anti-bias.

Young children love to hear their names in stories. It is good to base stories on the members of your group and on the community in which they live.

Sometimes children can tell the story, or part of the story, themselves. Here again a tape recorder can be useful so that the children can listen to the story again. Sound effects create a lovely atmosphere during story rings, and help to hold the children’s attention. Older children could devise their own sound effects for the story.

The story should be age-appropriate and suitable for the audience.

How to select suitable stories for young children

You need to have a collection of stories available that you can read to young children.

- Stories that deal with objects, places and people that the children know and are familiar with

- Stories that include unfamiliar people, places and events, so that you broaden the children’s knowledge

- Fantasy stories about fairies, giants, monsters and so on, which are essential for developing the children’s imagination (take care not to use very frightening stories, as some children become easily disturbed)

- Rhyming stories, such as Dr Seuss

- Stories where the same sentences or phrases are repeated in the story, as young children enjoy repetition

- Humorous stories

- Stories should be culture fair and anti-bias. Avoid stereotypes, for example where only daddy goes out to work and only mommy cooks; where all families consist of two parents and two children and all old people are sick or frail. Include a variety of cultures and pictures.

Routine activities

The routines in

the ECD daily programme include: clean up time, bathroom time, eating times

(snack and lunch), and nap time. The learning opportunities here are around

developing independence and self-reliance and learning about health, safety and

good manners.

Effective transitions between activities

When you implement

your ECD centre programme, you will find that it’s sometimes challenging to get

the children to move on from one activity to the next. Some of them might not

like the next activity you have in mind (for example clean-up time) and some of

them might just be enjoying the current activity a lot (perhaps painting or

playing outside).

Here are some practical tips for constructive transition times:

- Sing with the children while moving from one activity to another or move in different ways, for example tiptoes, sway, fly like birds to the next activity. This will help children to become excited about the next activity

- Choose a method to signal the start of a new activity – and allow children to become familiar with it. For example, play a simple tune on a recorder (flute) that learners recognise. After a while of repeated use, a few notes will alert children and they will gather for the new activity. A gentle musical signal is preferable to a bell or harsh sounding instrument

- Divide the children into groups. For example, say all the children with short hair go to the bathroom first and all the children with long hair go second. The next day children with lace-ups can go first and children with sandals can go second, and so on

- Let the children sing a song about tidying up to change it from a task to something enjoyable and sing "well done" to those who participate. If this is a regular daily routine, it provides an opportunity to use other languages that only some of the children may know. You can take a simple tune and make up your own words in a variety of languages. In this way, what might be an unstructured, potentially unsettling and disruptive time becomes more of a learning experience

- Tell the children what they will be doing next before you ask them to pack up and move on to the new activity and direct specific tasks especially to those who become unfocused during transitions. They like to know what’s going to happen next as it gives them a better sense of security and control.

3.5 Ensure that the programme provides a balance

The balance that you need to ensure that your programme provides should be:

- Between indoor and outdoor activities

- Between

individual, small and large group activities

- These activities need to support the development of children and be appropriate to the development stages of the children.

3.5.1 A balance between indoor and outdoor activities

Indoor activities: In the ECD daily programme, there are many opportunities for indoor activities. Usually children participate in rings and use activity zones e.g. creative art area, literacy/reading area, fantasy play area. While movement rings provide opportunities for physical movement gross motor development, generally indoor activities focus on the other developmental domains.

Outdoor activities: To best support children’s holistic development, the ECD daily programme includes both inside and outside activities. Usually outside activities are physical and encourage gross motor function. So, when children climb ropes, peddle tricycles, play on swings, hop, skip, run and jump and so on, they exercise their physical muscles, build fitness, and develop feelings of well-being that accompany physical activity. In a society where children are more sedentary through watching television, playing computer games and travelling by car or taxi.

Usually, the ECD practitioner will provide opportunities for outdoor sand and water play (supervised) where learners can measure, pour, build, float and generally exercise their fine motor, creative/imaginative and cognitive skills.

Of course, not all ECD centres have an outdoor play area. In these cases, the ECD practitioner must find opportunities to take children to a nearby park, and offer the chance for physical movement inside the playroom.

3.5.2 A balance between small and large group activities

Although group work is an important technique in a child-centred ECD playroom, there is also a place for individualised activities. Individualised activities are specially chosen for a particular child. These types of activities are often non-social in nature. The children do not interact with others in this type of activity. Instead, they either work alone or interact only with you, the ECD practitioner. These individual times can be used to work on weaker areas or to provide emotional support when children need it.

Learning activities can also be more or less group-orientated and children should have opportunities to work on their own with a puzzle, draw a picture, build with blocks or look at books. Children are forced into group situations and shared space during music, movement, story and morning rings.

As humans, we are social beings but sometimes we all feel the need for solitude (being alone). An ECD environment needs to have sufficient space for children to be able to work alone without being forced to share with others.

Babies and toddlers are self-centred by nature and only engage in more social play after three years of age. The younger the child, the more individual activities are needed.

Group size is also a consideration. Children need to experience being part of the playgroup group and also groups of only four or five children as the level of interaction required of them differs.

3.6 Ensure that the programme can be implemented in the given context and within available resources

When you plan your ECD learning programmes, you need to ensure that the learning activities and experiences you provide for young children are appropriate to their age and stages of development. This is known as developmentally appropriate practice (DAP).

Every ECD context is different. For example, one ECD centre may be very small, providing care for the babies of six working mothers in a middle-class suburb; another one may offer morning only care, but may be large with playgroups in all the age categories. Can you see why the ECD learning programmes for the two centres would need to be different?

Analysing your context consists of these five steps:

Step 1: Identify the factors that impact on the ECD programme.

Step 2: Identify the developmental ages and stages of the learner group.

Step 3: Identify the needs of particular learners, for example a child with specific learning disorders (SLD or dyslexia).

Step 4: Identify relevant ECD-related frameworks.

Step 5: Reflect on your analysis.

3.7 Ensure that the programme complies with relevant national policies and guidelines

Whichever model you choose to use in your learning programme, you will need to make sure that you follow the requirements of the national school curriculum. You are probably aware that the education system in South Africa is periodically revised and adapted to meet the needs of a changing environment. You will therefore have to contact the National Education Department (or a provincial branch) for up-to-date documentation about the specific details of the ECD curriculum.

However, we can provide you with an outline of the current educational curriculum and introduce you to the structure and terminology that will help you to understand the documentation.

a.

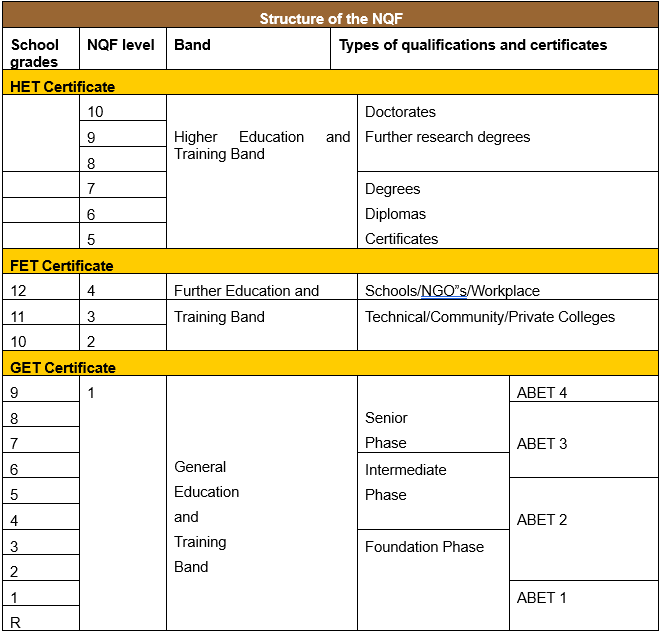

The structure of the NQF

NQF is one of the

abbreviations you will hear often in connection with the new education system. It

stands for National Qualifications Framework. As an ECD practitioner, you need

to know where early childhood development is located within the national

education system as a whole. The table below shows you clearly how the NQF is

structured. You will need to refer to this table constantly as you read the

next few pages. The table also shows clearly where early childhood development

(ECD) fits in. Please note that ECD is not part of the formal NQF, but young

children can enter the formal system from ECD playschools.

Now let’s look at some of the terminology you should become familiar with in order to find your way around the NQF. We will first look at the three bands of education, then at the NQF levels.

b.

Bands

There are three

main clusters or bands of education and training, namely:

a) the General Education and Training Band (GET)

b) the Further Education and Training Band (FET)

c) the Higher Education and Training Band (HET)

GET: General Education and Training

The GET feeds into

the GET band, we will focus on this part of the NQF chart. The GET band covers education

from Grade R up to Grade 9. Grades 1-9 are the nine years of compulsory

education, grouped into three phases: the Foundation Phase, the Intermediate

Phase and the Senior Phase. Grade R (shown as R, for reception year) falls into

Foundation Phase and is optional, but is encouraged. A learner can be admitted

to Grade R at age four (4) turning five (5) by the 30 June in the same year of

admission. The ECD phase caters for babies, toddlers and young children prior

to entering Grade R. The ECD phase is not compulsory.

FET: Further Education and Training

The FET band

comprises Grades 10, 11 and 12. An FET certificate, which is equivalent to a

matric certificate, is given at the end of this band, and signifies the end of

formal schooling. Grade 12 is thus the final exit point for schooling.

HET: Higher Education and Training

This band enables

learners to obtain diplomas and certificates offered mainly by colleges, and

degrees offered by universities and technical colleges (formerly known as

technikons).

c.

NQF Levels

The NQF has ten

levels of qualification. The whole GET band (Grades 1- 9 or ABET 1- 4) makes up

the first level of the NQF. The learner can receive a qualification at each

level by achieving the credits required to complete that level. The NQF makes

it possible for learners to move up the levels and across the different areas

of the NQF structure.

The NQF was designed to allow learners to build on what they know as they move from one level to another. It allows for more flexibility than the previous education system, especially for people who were unable to receive full schooling as children. We consider the differences in more detail in the next section (see table 3).

d.

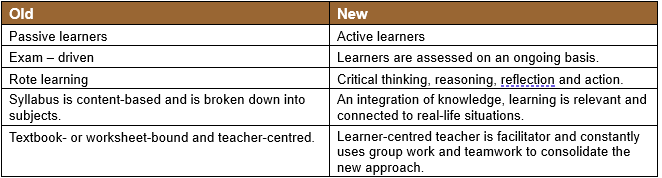

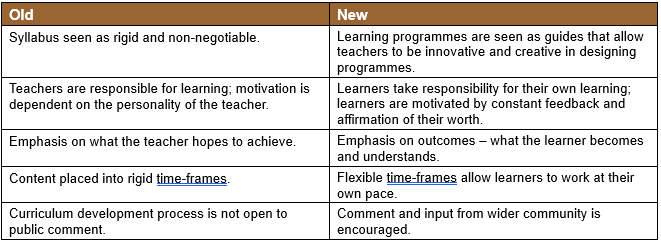

Teaching methodology

Within the national curriculum, the teaching

methodologies have shifted from the old content-based approach to an approach

that is outcomes-based. The table below explains the difference between these

two approaches.

e.

Learning outcomes

As you know from

your own studies, outcomes-based education means that you learn in three main

ways:

- You acquire knowledge: what you need to know and understand.

- You acquire knowledge skills: what you need to be able to do.

- You acquire attitudes and values: what you feel and understand and your approach to the world around you.

These three aspects are incorporated into learning outcomes that explain precisely what learners need to master at each level of their education. For the foundation phase, these learning outcomes are written up in the revised National Curriculum Statement which you can obtain from the Education Department.

f.

Foundation phase learning programmes

During the foundation

phase – including Grade R – learners have three main learning programmes:

- Life skills

- Mathematics

- Language

Within the ECD phase, the learning programmes are designed to encourage learning and development in the early years, and to equip learners to enter into Grade R at age four to five.

If you have any questions about the leaning programmes for Grade R and the foundation phase, or about implementing the national curriculum guidelines, contact your local Grade 1 teacher. He or she will be able to assist you.

3.8 Develop learning programmes to enhance participation of learners with special needs

The term "learning programme" includes all the topics or themes and all the activities that are planned on a weekly and daily basis. We will focus on the various activities in this section, as a child with special needs may be unable to participate fully in certain activities only. Consider, for example, a child in a wheelchair: while he may not be able to skip in a music ring, he is able to participate fully in a story ring.

Each child, whether he or she has a special need or not, has areas of strength and areas of weakness. Think of yourself: you have some skills that are well developed and others that are not. When you plan activities, you need to be aware of all the special needs in your class so that a particular child does not feel excluded from several activities on the same day. Proper planning is the most critical factor in the success of an activity and in the participation of all children.

Special needs, symptoms and requirements

In ECD programmes, we are very aware of looking at children holistically. We donâ€t focus only on their cognitive skills but recognise that other aspects, such as their social skills, are also vitally important.

The figure above shows children develop in many areas at once. We must consider these holistically (as a whole).

Let’s look at a list of special needs or barriers to learning that you may come across in these different areas. Please don’t just skim through this list, but to try to picture a child in each situation.

a. Physical special needs

Physical special

needs are usually easiest to identify and include the following:

- Cerebral palsy, the loss of a limb, spina bifida or severe burns may restrict movement. Children may need assistive devices such as wheelchairs, splints or crutches

- Visual impairment can range from being blind to a child needing glasses for reading

- Chronic or long-term illnesses such as cancer, Aids, epilepsy, diabetes, asthma or TB may prevent a child from being active, but may also cause them to be away from the ECD centre for lengths of time. They may also need medication while they are at your ECD centre.

b. Environmental special needs

The following are

some of the circumstances that might lead to environmental special needs:

- Children may come from impoverished homes where they lack the physical resources needed for normal development. These resources include adequate shelter, food, clothes and educational resources like books and toys

- Poor nutrition often occurs in poor communities. However, keep in mind that many wealthier children live off "junk food" and also don’t get the nutrients they need from their food

- Children may have to travel long distances and leave home very early to reach the ECD centre on time. If they had to get up at 4:00, they may already be tired by the time they get to you at 8:00.

c. Cognitive special needs

Cognitive special

needs include the following:

- Foetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). Children born with FAS may be cognitively challenged or may learn at a slower pace than other children

- Cognitive challenges such as Down syndrome (also called Down’s syndrome)

- Giftedness. Some children are particularly gifted and have the ability to learn more and at a faster pace than other children

- ADD (attention deficit disorder) with or without hyperactivity. Children with ADD or ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) have a very short attention span and are easily distracted

- The autism spectrum, including PDD (pervasive developmental disorder). Children with disorders in this range have difficulty in focusing on tasks and prefer to be "in their own world", so it is difficult to engage them in activities

- Special learning disorder (SLD), which used to be known as dyslexia in the past. Children with SLD have perceptual disorders and thus their brain has difficulty interpreting the signals it receives. They may have perfect eyesight, but will, for example confuse a "b" and "d".

d. Language special needs

Language special

needs include the following:

- Many children are forced by circumstance or by their parents to learn in their second or third language. This is very common in South Africa and can put children at a huge disadvantage. Imagine understanding only three out of ten words when someone speaks to you! While children do catch up and learn language quite quickly, they may miss out on basic concepts, which can slow down their progress

- Speech impediments such as stuttering or lisping may occur. Children may be teased and feel embarrassed to speak and thus do not practise their speech skills. This often has an impact on their socialisation at school

- Aural (hearing) impairment, which could range from a child being deaf to needing a hearing aid. These children learn speech at a slower pace.

e. Social and emotional special

needs

Cognitive special

needs may arise due to the following circumstances:

- Children may be victims of abuse or neglect

- Children may be isolated because of their religion or culture. For example, a Muslim child in a Christian school or ECD centre may be teased when she wears a scarf or refuses to eat food that is not halaal

- Some children have behaviour problems. This may be a result of poor parenting or a neurological dysfunction such as autism, discussed above.

This is a fairly comprehensive list of barriers to learning or special needs that you may come across. However, there are others that fit into these categories that are not covered. Remember that the most important thing is how you adapt to each learner’s particular needs.

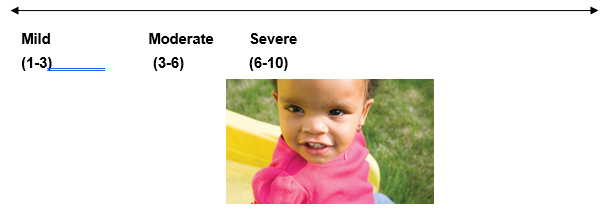

Another important point to remember is that special needs are unique to each particular child and may differ in severity. Two children who both have ADD may differ in their abilities. While one child may be able to focus and concentrate on a task for ten minutes and complete it with their ECD facilitator’s encouragement, the other may only be able to focus for two minutes before getting up from the table – even when the facilitator is assisting her.

These differing abilities are placed on a continuum (range or spectrum), which is illustrated below. Sometimes a rating scale is linked to this, for instance 1 to 10.

Signs and

symptoms of more commonly occurring special needs

Please keep in

mind that not all children with the special needs that we mentioned will

display all of the characteristics. These are merely a guideline to assist you

in identifying children who may have a special need. You will have to do

further assessment in order to determine the special needs and before referring

the child to further support.

Attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

If hyperactivity

is not present, the children are often seen as daydreamers or labelled "lazy".

They tend to be quiet, passive and clumsy and are often overlooked in a class.

If hyperactivity is present, you may observe that the child:

- Fidgets, squirms, appears restless and has difficulty remaining seated

- Is easily distracted and has difficulty in sustaining attention

- Has difficulty in waiting his turn and blurts out answers

- Has difficulty following instructions and shifts from one uncompleted task to another

- Has difficulty playing quietly and talks

- Frequently engages in dangerous actions.

Children with ADHD are sometimes called "impossible", because they:

- Are difficult to discipline

- Are intelligent, but do not respond to reasoning

- Nver truly explore in a quest for knowledge

- Don’t generally like to be hugged and cuddles

- Are easily frustrated

- Are strong-willed and have temper tantrums.

Cognitively challenged children

Children with cognitive

challenges will tend to:

- Have a developmental backlog and not reach milestones within the broad timeline of six months

- Be slow in understanding and responding to instructions

- Be unable to follow stories if there are no illustrations

- Have difficulty in learning new songs and rhymes

- Be easily confused by new or different objects and situations

- Have difficulty in imitating more complex movements

- Have difficulty in repeating long words or sentences

- Prefer the company of younger children

- Possibly be grasping more abstract concepts.

Hearing impairment

You should suspect

hearing impairment if you notice that a child:

- Often interprets instructions incorrectly

- Turns his/her head to listen

- Watches the teacher’s lips and cannot follow what the teacher is saying if she covers her mouth or turns away (the child might move around during story to be able to lip-read)

- Finds it difficult to locate the source of sound

- Speaks too loudly or too softly

- Finds participation difficult in large groups

- Doesn’t pay attention

- Cannot follow instructions if there is moderate amount of noise in the group

- Finds it difficult to relate stories

- Appears to be disruptive or not to listen.

Pervasive developmental disorder (Autism scale)

Autism and related

disorders are not always easy to recognise. Here are some pointers:

- Up to age of two years, the mother sometimes has a feeling that all is not well with the child. She may notice delayed speech, poor motor development and self-stimulation behaviours

- In early childhood, poor social contact becomes obvious. The child’s play is often repetitive and meaningless and she may develop peculiar preferences or dislikes for food

- At school-going age, language development is obviously delayed or disturbed

- They display abnormal reactions to normal stimuli such as background music in a restaurant

- Motor control and imitation of movements is poor

- These children may develop particular skills in areas that interest them

- Behavioural problems like temper tantrums may continue.

Other signs of impairment or disability

The following are

often referred to as soft signs" because they are not very obvious and can

be easily overlooked.

Motor development

Take note of:

- Effects on both gross and fine motor abilities

- Delays in development of skills

- Poor quality of movements and skills that are not well developed

- Clumsiness and poor motor planning skills

- Difficulties with balance, and poor spatial orientation

- Hand dominance that is established late (after five years of age), so children often swap hands when drawing

- Self-help skills that are poorly developed, for example a child cannot do up buttons when dressing (at an age when peers can do this).

Language development

Pointers to look out

for include:

- Delays in reaching speech milestones

- Poor articulation and quality of speech.

Social

Notice when a child

is unable to "read" social situations and has a poor concept of

personal space.

Cognitive

Cognitive signs

include:

- Poor memory, struggle to engage in age-related problem solving and to see cause and effect

- Difficulty in making decisions

- A poor level of symbolic play

- A lack of creativity - the child will rather copy others than come up with their own ideas

- A tendency to be very passive in their learning

- Difficulty in abstract thinking

- Difficulty following more than one instruction at a time.

Hypotonic (low tone)

Children with low

tone may show the following behaviours:

- Try to act “cute†for their age and opt out of activities where possible

- “Flop out†and lie down as much as possible; for example, they will not sit and watch TV but will drape themselves over the chair

- Avoid doing any motor tasks and rely on listening and verbal skills

- Use spontaneous movement and rush around when they are required to move

- “Fix†in various positions (w-sitting is very typical); W-sitting is a floor sitting position in which children appear to be kneeling, but they are actually sitting with their bottom on the floor between their legs. Their legs form the shape of a “Wâ€

- Cope with skills they are taught or have to copy, but have difficulty when they have to do motor planning of their own

- Use gestures if their speech is delayed

- Rely on others to do tasks for them

- Display silliness and clowning, or switch off and ignore stimuli.

Down syndrome

Down syndrome has

both physical and cognitive characteristic signs:

- They have low muscle tone

- The stomach is prominent, and they have a small head, which is flat at the back

- Face appears small and flat with a small mouth and a tongue that often protrudes (sticks out)

- Epicanthic folds (skin of the upper eyelid that covers the inner corner of the eye) over almond-shaped eyes that slant upward

- Small low-set ears

- Neck is short and broad, hair is sparse, fine and straight

- Hands are small and square with short, stubby fingers and atypical fingerprints

- Skin is often dry and mottled

- The child is short and stocky in stature – this is more noticeable from four years of age – with a tendency to be overweight

- Language development is delayed and the child is slow to learn new concepts.

Visual impairment

Be alert to visual

impairment when you notice that a child:

- Rubs her eyes frequently, especially when doing close visual work

- Shuts or covers one eye, tilts head or has unusual facial expressions like squinting, frowning or blinking with close visual work

- Complains of eye discomfort

- Shows sensitivity to light

- Holds a book incorrectly – upside down, too close or too far away

- Fail to see detail in picture

- Has excessively watery eyes or red, inflamed eyes that don’t get better

- Has eyes that look dull or cloudy, with pupils that are unusual in size or colour

- Appears clumsy

- Seems afraid to move around in unfamiliar surroundings, and avoid balls games

- Show developmental delays in all areas.

3.8.1 Evaluate a range of learning programmes and point out special needs, strengths and weaknesses

When evaluation takes place within an ECD setting you have to pay special attention to the quality of the programme. There are various organic factors that contribute towards this. There are five dimensions of quality within and across settings and systems. These are:

- The ECD programme must be in alignment with the values and principles of a community or society.

Programmes may differ radically for example, in urban versus rural areas (Dahlberg et al, 2007). The different communities may solve in different ways the tensions between "adult-centred" and "child-centred" views, between valuing children fundamentally or instrumentally for the work they can or will be able to do. It must also include the ability to cater for special needs.

- ECD resource levels and their distribution within a setting or system

This measurement will include material resources, human resources, the educational level of an early childhood caregiver, the skills level of a health worker as well as the food for the children and print materials.

- Physical and spatial characteristics associated with meeting basic needs and minimising environmental dangers

South Africa is a developing country. Being exposed to accidents and unforeseen threats is a key feature that affects quality, and the nature of the threats also depends on whether it is a rural or urban setting. Norms may differ but safety standards need to be clear. This includes boundaries to prevent large animals (such as cattle) from entering a setting where children are present, convenience issues for children or parents with disabilities, and the ability to address risks that arise from poor conditions, conflict or natural disasters.

- Leadership and management

The priority that ECD enjoys and the response to concerns such as the turnover of ECD providers or teachers are leadership and management issues. This includes human resource factors such as local staffing shortages and learning for ECD practitioners.

- Interactions and communications

In places where ECD is not a cultural norm, the language and mode of communication are often the first experiences that communities have of a programme. This is especially important for reaching minorities, such as the poor or ethnic groups who experience discrimination, and even children or parents with disabilities. Effective communication and involvement is critical to ensure ECD service quality.

3.8.2 How to modify learning programmes to enable learners with particular special needs to participate

Learning programmes can be modified to enable learners with particular special needs to participate. You can modify any or all of the following:

- Design of learning programmes, resource materials, trails and routes

- Choice of activities, examples and language

- Timing and duration of programme, etc.

You can also modify:

- Actions

- Arrangements

- Learning programmes

- Materials.

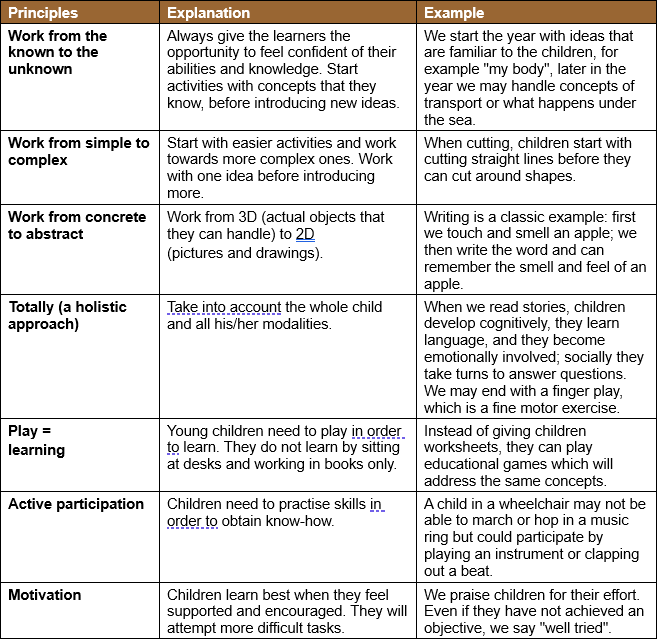

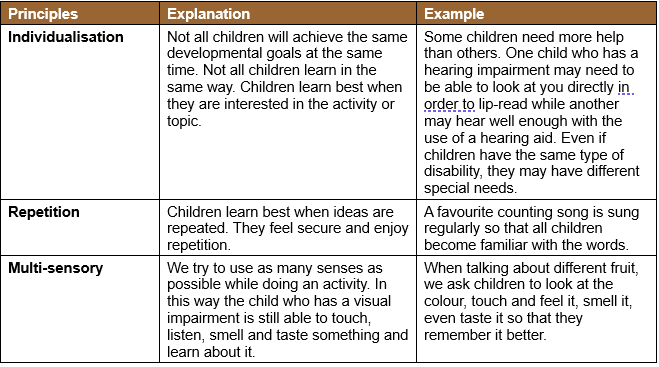

We can use didactic principles (or teaching principles) as a basis from which we can adapt activities in order to maximise the learning for all learners, but especially those who have barriers to learning.

The following table shows the didactic principles and how they apply to the design of activities:

Examples of activity

adaptations

The following are

some ideas of how activities could be adapted to suit children with special

needs. They are not rules but guidelines

only. Use them to spark your own ideas and creativity to adapt activities to

the needs of the children in your care.

a. Environment

- Children who are easily distracted may need to work in a quieter corner of the clas

- Buildings may need to be adapted and ramps built so that children in wheelchairs can access the garden.

- Children with a hearing impairment find it difficult to follow instructions if the classroom is very noisy. You may need to get the class to be quiet before telling the class what to do next.

b. Time and duration

- Children with ADD have shorter attention spans and find it difficult to concentrate for long periods. You may need to allow them to get up from a table-based activity to walk around the class, before returning to complete their activity

- Visually impaired children are often sensitive to bright light so outdoor play should happen earlier in the day to avoid the sharp midday sun

- Children with diabetes need to eat small meals at regular intervals. You may need to adjust your snack times to accommodate a child who needs to eat.

c. Resources

- Children with a physical disability that affects their hands may have trouble using a string when threading beads. These children would cope better if they used a kebab stick to thread the beads onto

- A child in a wheelchair may be able to ride a tricycle if straps are added to the pedals to keep their feet in place.

d. Assessment

You must make sure that assessment activities do not disadvantage a child but are adapted to test the same concept as the original activity. A child who is learning in a second language may not be able to name shapes but could be asked to point to a triangle, square and so on. In this way their concept of shapes is still being tested but their language abilities are not handicapping them.

e. Group vs individual

- Children learn best in a one-on-one situation where they get all the attention and activities can be individualised. This may not always be possible, but if a child is cognitively challenged and learns more slowly than the group, he will benefit from having extra time to consolidate a concept

- Small-group teaching is a valuable method, except when children become aware that they are being categorised. This may happen, for example, when a group who learns concepts quickly is called the "hares" and the slower group the "tortoises". Children are more sensitive than we may realize. Mixed-ability groups work quite well, as stronger learners can help those who are struggling.

f. Buddy system

- Children who are shy or withdrawn will benefit by having a "special" friend who plays with them and partners them in activities

- Children can help their physically disabled classmates by fetching toys for them or pushing their wheelchair in a music ring

- A child who is hearing impaired may not hear the bell ringing after outdoor play, so a friend could fetch them wherever they are in the garden.

This system is of benefit to both parties, as the child who is helping also feels important and his or her self-esteem is raised.

3.8.3 Appropriate attitudes and behaviour in relation to learners with a range of special needs

As an ECD practitioner, you are often the first adult outside of the immediate family with whom a child spends extended periods of time. This places a huge responsibility on you, not only in terms of early identification as discussed, but in the way you deal with this child. Your attitudes towards a child with special needs can be the critical success factor in the time she spends in your class. If you are positive towards the child with special needs and show her unconditional acceptance, she will most likely thrive and progress.

Let’s look some key aspects or characteristics of your role as an ECD practitioner in relation to children with special needs. Ideally, you need to be:

- A role model

- Loving

- Creative

- Flexible

- Enthusiastic

- Patient

- Confident

- Humble

- Motivational

- Setting realistic goals

- Encouraging independence

- Prioritising safety

- Managing behaviour.

Role model

The other children in your class will be guided

by your attitude towards the learning with special needs. If you are impatient

with the child, they will be too.

Loving

All children have

the right to be loved. It is not always easy to hug a child who is dirty or who

smells because he has not had a bath in many days, or who is destructive and

hurts other children. However, it is important to see they will respond

positively in time.

Creative

You will have to

look at the challenges that a particular child with special needs experience,

and you will have to come up with solutions. While you may be able to consult

with others or follow guidelines, you will often need to "think out the

box" to find suitable solutions that are practical and affordable. A good

example is a child who needs a footrest – this can be made by taping together old

telephone directories.

Flexible

Be prepared to

adapt activities and tasks, and even your programme, in order to accommodate

the special needs in your class.

Enthusiastic

Show children with

special needs that you are keen and happy to assist them.

Patient

A child may not always

have good urinary control and may wet herself several times in a day. If you

become impatient with the child, she may become more anxious and may wet

herself even more often.

Confident

Be confident that

you are indeed able to assist the children in your class. Your confidence will

inspire them to be confident of their abilities and to take small risks in

developing their skills. Believe in children and they will believe in

themselves. This self-belief can be the start of great achievements.

Humble

There are times

when you need to be humble (modest) and admit that you have made a mistake or

do not know enough. Never be afraid or too proud to ask for assistance; there

are many people and organisations who may be able to help you.

Motivational

Motivate the

children in your care to extend themselves (do more than what they think they

can) and to develop themselves to their full potential. Don’t look only at

challenges; look at possible solutions and encourage children to be all that

they can be. Remember that a child with special needs is still a child who has

aspirations and goals.

Setting realistic goals

While encouraging

children, be careful not to set goals that are too high and that children will

not be able to reach, as this can be harmful to their self-esteem.

Prioritising safety

You need to be

aware of safety issues, especially with aids such as wheelchairs, crutches or

walkers. A wheelchair could be overturned if another child is pushing a friend

too fast, and injuries may occur. You need to strike the balance between fun

and participation and safety.

Managing behaviour

Just because a

child has a special need that does not mean that you should not discipline him

or her. While you may have to adapt methods - especially for children with

emotional problems - they cannot be allowed to get away with socially

unacceptable behaviour, because they will, like any other child, become part of

society. This is an area that many caregivers find very difficult as they feel

sorry for the child.