Unit 1 Online Study Guide

Learning Unit 1: Use facilitation approaches and appropriate activities

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to use facilitation approaches and ensure that facilitation uses developmentally appropriate activities. You will:

- Understand and apply child development and child development theories

- Ensure that the facilitation approach responds to cues provided by the children, while providing structure and experiences for their own development

- Ensure that the facilitation approach is multi-cultural, avoids bias and is sensitive to the existing knowledge, experiences and needs of the children

- Ensure that the facilitation approach takes advantage of teachable moments

- Ensure that facilitation uses developmentally appropriate activities that are fun, relevant and meaningful to the life-world of the children

- Identify activity purposes and ensure that they are consistent with given frameworks, guidelines and/or plans

- Ensure that activities identified are appropriate to the given context and support the developmental outcomes.

Use facilitation approaches and appropriate activities

As ECD practitioners, we know that babies, toddlers and young children move through particular stages of development as they grow and develop. We know that these stages have been analysed and documented by child development experts. The developmental stages are grouped according to the ages of the babies, toddlers and young children. However, we also know that each baby, toddler and young child is unique. Each child grows and develops at his or her own pace. Each child will go through each developmental stage when it is right for that child. We know we need to be sensitive to each individual child’s needs, to help each child develop in a way that is just right for him or her. All this knowledge will help you to identify activities within a daily and/or weekly programme that support the development of babies, toddlers and young children in your playroom. This knowledge will also help you to identify the resources and space you need for these activities.

1.1 Understand child development and child development theories

In order to ensure that facilitation uses developmentally appropriate activities that are fun, relevant and meaningful to the life-world of the children, you have to understand the various domains and stages of development.

It will be useful to briefly revise the main theories of child development that you encountered previously.

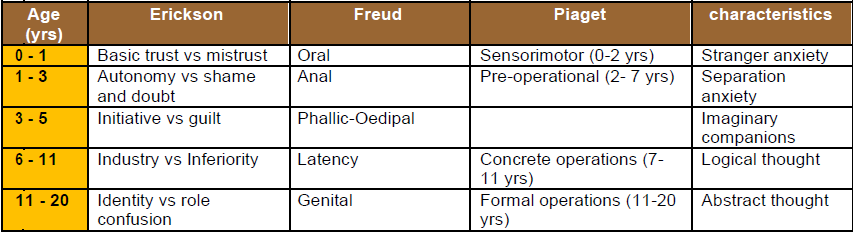

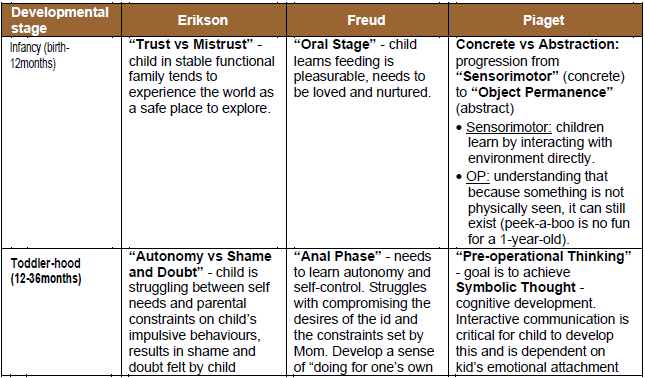

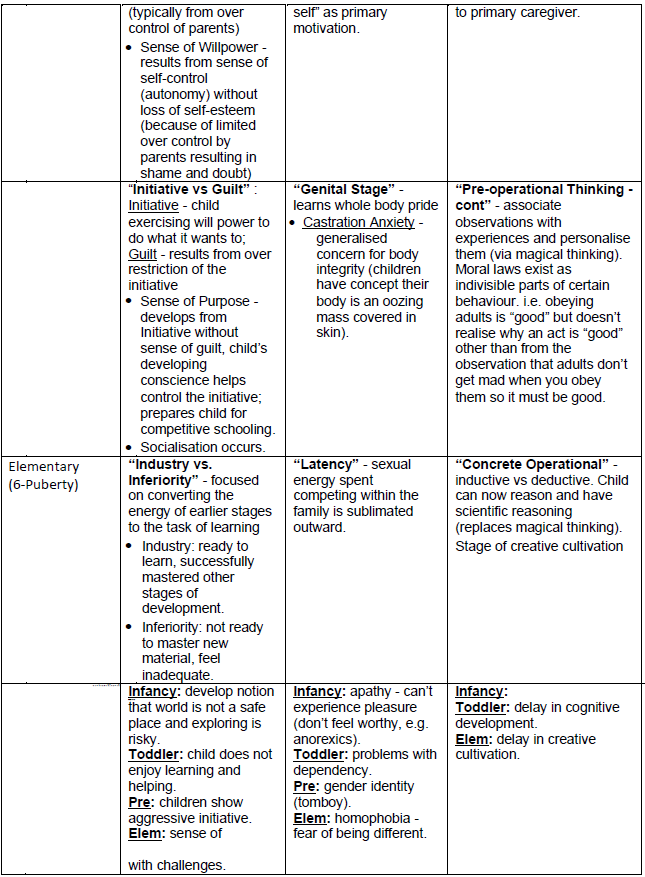

A comparative table of leading theorists

Appropriate activities

Having fun is the easiest way to learn something. Make sure you provide activities that are creative and exciting, drawing on the ideas, actions, and preoccupations of the age group you are working with. The children’s developmental age must be the guiding factor in preparing your learning programme and in guiding your own expectations and responses.

Consider how your knowledge about child development can help you facilitate better, by knowing what kind of learning takes place at different ages:

Concrete learning experiences

Children from birth to three years of age primarily use their senses to explore concrete objects. During this phase they have to see, hear, touch, taste and smell to learn.

Semi-concrete learning experiences

Children

between the ages of three and five years of age are able to relate pictures to

the real objects that they explored earlier.

Abstract learning experiences

Children from age five can grasp the meaning of

symbols and abstract concepts that cannot necessarily be explored by their

senses.

(Maree & Ford 1996:

9, 10, 32)

Although these different learning styles are generally true for these age ranges, the learning process is like collecting apples in a basket. Once a child has a skill, he or she can use it during the phases that follow. For example, the five-year-old child who is capable of abstract learning (for example building with Lego or matching shapes in a complex puzzle) will still enjoy using his sense of touch to explore the texture of new objects (for example, the squishy feel of his baby brother’s dummy).

This knowledge will assist you as the facilitator to create activities that will specifically focus on the child’s developmental stage. For example, include objects of different textures in the baby room.

Developmental outcomes

Suitably

planned learning activities that support the developmental needs and abilities

of the group will have a stronger chance of succeeding. This is because

children will be working at a level that they can cope with and thus will learn

more readily.

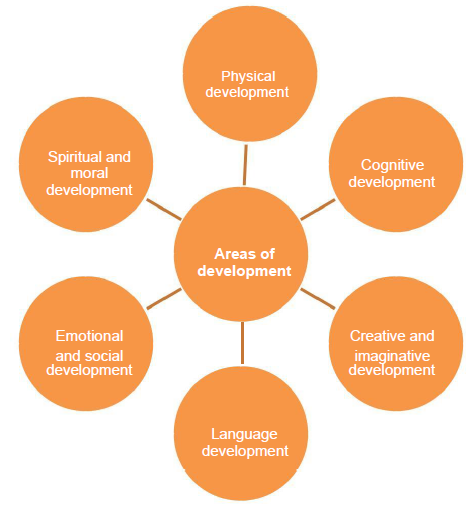

You should cover all of the following areas on a daily or weekly basis to ensure that holistic development is taking place.

The main domains of development

You need to plan appropriately to ensure that you cover the complete spectrum within the developmental age and stage of the children in the group.

For instance:

- Most of the development needed during the baby stage is physical. You will have to provide opportunities for them to be on the floor so that they have a chance to roll and crawl. Babies that are held all day or left in a cot will not develop appropriate skills

- Young children also need physical stimulation but this involves more challenging equipment such as obstacle courses, jungle gyms, music and movement sessions. If you do not expose a child to galloping in time to music, they will not easily learn the skill.

Weekly programme

In addition to daily programmes, we need to consider

weekly as well as longer term planning.

Often ECD centres will have a weekly routine that may allow for particular activities on certain days e.g. “make and bake†on a Friday. They may also need to accommodate extramural activities that often take place in the afternoons when the schedule is more relaxed. Themes will often slot into these weekly schedules too.

Themes help us to focus our learning objectives and encourage integrated learning. They also create a shared context for further meaningful interactions between practitioner and child, and between the children themselves. Choosing exciting themes and including new information stimulates the child’s curiosity about the world around them, helps them to make sense of what they already know and encourages active learning.

Activities in the playroom are usually linked to your selected theme. This includes outings or demonstrations and talks from outside visitors. For example, if your theme is the sea, you may read stories like Eric the Hermit Crab or The Sailor Dog. You may set up creative art activities like making shell collages or sand paintings. You may use movement activities that require children to “act†what it feels like to be a crab, dolphin, or shark. In other words, you provide opportunities for children to explore the theme experientially in many different ways.

Some ideas for themes can include:

- Seasons

- Transport

- Families

- Insects

- The sea

- Wild animals

- Pets

- Sports

- Health and nutrition

- Musical instruments

- Holidays.

Long-term planning

Longer-range

planning is also important so that themes can run in a logical sequence and so

you can take outings and major events into account. These can be used to a

positive effect to change your ECD classroom and to provide activities that

stimulate further interest and learning e.g. Arbour day – your theme

would be around trees and growing and you would have access to posters in the

newspaper.

1.2 Use appropriate facilitation approaches

When you plan learning activities, try to include both known aspects as well as new aspects. This will ensure that children build on previous experience and face a challenge. For example, if children are making a nature collage, use leaves and twigs, but also provide seeds, seedpods or dried flowers that children have not seen before. The known objects - leaves and twigs - will give children context. They know that they find leaves and twigs in nature. The new objects - the seeds, seedpods and dried flowers - will stimulate children’s curiosity. They may want to talk about how seeds grow into plants, or how flowers are dried and pressed. These new objects help to extend their world, and open up to new possibilities beyond the known.

Present themes or

concepts that allow experiential learning

Choosing

a theme or concept as the focus of activities makes it easier for you as a

practitioner, but you should have a flexible approach for the sake of the

child. Adapt themes from year to year, to be sensitive to the needs of you

class. Keep the material fresh and challenging for you as a practitioner. The

most important part of the learning experience for the child is the opportunity

for concrete, sense-based experience. The children should be able to touch,

smell, taste and explore. The point is not to introduce new knowledge but to

allow the child to explore. This exploring will uncover new aspects of the

family.

Make activities

meaningful to the life-world of the child

This has already been mentioned in other sections

above. To be sure that you are catching the child’s interests with your

activities, check whether your activities include the following references:

- The culture language and context that the child knows

- Stories about children of the same age of the class

- The visible world outside your class building (garden, play area, other nearby buildings or houses, home activities like cooking, shopping with parents, helping parents with chores)

- Fantasy content that is safe and appealing to the age group, for example a teddy bear’s picnic for age 2-4 or traditional animal stories for age 5-6

- The developmental crisis points or growth that the child may be preparing to deal with, for example water play with containers to provide practice in problem solving for pre-operational or intuitive reasoning (children younger than 6).

1.2.1 Ensure that the

facilitation approach responds to cues provided by the children

Your

interaction with the children and attention to their verbal and behavioural

signals and messages mean that you should respond to them all the time, whether

you are aware of it or not.

From now on, that awareness must be sharpened so that you respond purposefully to any signals that the children are giving out, about their learning needs and preferences. With some practice, you will learn to tune in to their signals (which we call “cuesâ€).

A cue is a signal, in words or behaviour that implies a need for an appropriate response.

In this context, the cue comes from the child and the response should come from the playground facilitator.

Example 1:

Thando: (Grunting and stamping her feet at home time, struggling with the laces of her takkies).

Facilitator: Here Thando, let’s practise together on this lacing board for a minute. Then in a few days it will be

easier. I’ll help you tie your laces when we’ve done the practice. You can also practise once

more at home when you take you tekkies off at bath time this evening.

The cue given by Thando was nonverbal, and was given at going home time, when the facilitator’s attention should be focused on saying goodbye and handing over children to parents who are collecting them. So you should use the moment for teaching the skill in whatever way you can.

A good opportunity for teaching something is when the child voluntarily asks for input from the facilitator, by means of a question or request, or by indicating openness to learning. We call this the teachable moment, because it refers to the moment when the child is ready and motivated and shows a need for learning.

The response given by the facilitator above is an ideal full response. A shorter, more focused, response would be:

Example 2:

Practitioner (to Thando): Let’s tell the laces where

to go and I’ll help you lace them up: Over, under, round, hold, over, under,

THROUGH! The practitioner should then make a note to offer

Thando the lacing board to practise on the next day.

Another example of a cue might be when the child is busy playing outdoors and apparently having a good time but really feels out of control.

Example 3:

John (screaming anxiously): Watch out, Maria, watch out, I’m going to kick

you, you’re in the way!

Practitioner: It’s okay John, I’m here with Maria and she’s standing aside. But maybe you don’t feel safe, swinging so fast? It’s a good idea to practise swinging more slowly at first, just like the Olympic gymnasts do. They have to practise slowly so that they can become the stars in the end. I’m just going to slow you down a bit by pulling you back once. Okay?

This scenario on the swing indicates that John enjoys the gross motor activity of the swing but lacks the muscular control and understanding to manage his movements within a range he finds comfortable. The cue he is giving is his screaming and anxiety about possibly hurting his friend Maria. The practitioner responds not by humiliating him or pointing out his inadequate control, but encouraging him to model himself on sporting heroes who are impressive because they exercise control. John will eventually learn to monitor and control his own movements on his own, with practice, but he needs someone to take control of the situation for him immediately (as shown by his anxious screaming). The practitioner here should be calm, reassuring, normalising the event by encouraging him to play safely and slowly until he feels more in control. By one simple pull on the swing, she brings it under control for John and he can carry on and try again to go slowly.

The practitioner provides structure and experiences promoting child development. The practitioner’s response to cues from the child functions to promote child development in three ways:

- It takes into account the child’s learning needs at that moment (as in the examples, for the skill of tying shoelaces or managing a flying swing). The practitioner provides a corrective learning experience or the knowledge input so that the child can learn the skill

- It supports the child emotionally to manage the stress of the situation so that she can feel more confident. This encourages her to try to find her own solution or attempt to learn the skill with a little help

- It is also important to the other children to see the adult taking charge of the situation for them, and removing the anxiety from the situation. This modelling of a calm response and a supportive adult role prepare them for behaving similarly when they are adults. It also means that the responsibility for control of the situation stays where it belongs, that is with the adult practitioner. As a result the children feel safe and can continue to play without stress.

How to attend to cues (signals about skills or emotions)

Now that you have an idea what a cue is, you may understand that any

request by a child for help or attention is a signal which you should respond

to with empathy and assistance, to make the most of a learning opportunity and

to promote the child’s holistic development. Usually cues are requests for help

with a particular activity which the child may be finding challenging. They may

be signals from a child that she is keen to learn something which she cannot

quite master and which she is finding frustrating, but could manage with a

little help. This links cues to Vygotsky’s idea that some skills may be not yet

accomplished but in the zone of proximal development as the child cannot manage

the skill without help, but is almost able to do so.

a. Active listening

This means that you should be listening and attending, observing not

just the surface communication but also the underlying messages which the child’s

behaviour is giving out. Any changes may signal something significant, and also

things staying the same when they shouldn’t, may be a signal. As an example,

you should question why a child who seems capable at gross motor tasks does not

improve and enjoy the challenge of the new jungle gym, when his peers are all

playing on it and acquiring new skills. A child who constantly asks for

assistance may be sending out a signal, not about the task but about a general

state of feeling helpless and vulnerable. To listen for cues means to use

active listening, focusing on the child’s communication and context with full

attention.

b. Observation

To observe the context

of cue, it is important to ask the following questions:

- What is the message in the behaviour?

- Does the child have a motive for this behaviour?

- Is there something else behind the behaviour that I’m not seeing?

For example, if Samba (5) who is a bright and capable child, suddenly wets herself two days in succession, this sudden lack of control may signal a serious physical or emotional problem.

The message in this behaviour is: it is very unusual for a five year old to wet herself (accidentally) for two days in succession. This message thus indicates that there is something wrong, which needs thorough investigation.

Does Samba have a motive to do this? Or perhaps is a way of seeking attention when other methods may not have worked? Is it likely that she would want to wet herself, and seem out of control?

What could be behind the behaviour? The first step would be to check her physical and emotional health.

1.2.2 Ensure that the facilitation approach is multi-cultural, avoids bias and is sensitive

It will help your facilitation skills if you know a little about each child’s culture in their family of origin or their caregiver’s family. It is useful to know about their home language, religious beliefs, cultural celebrations and lifestyle. This should form the foundation of your sensitivity to the child’s culture. Stay respectful in your behaviour, by avoiding the use of discriminatory language, slang or culturally biased remarks, and keep in mind that the culture of the ECD centre may not match the home culture of the child.

This gap may affect the child’s performance of tasks at the appropriate developmental level, because of language difficulties or attitudes to tasks. Some families may emphasise the importance of physical abilities and expect the child to do chores like cleaning shoes, helping to make sandwiches for school snacks, and making the bed, while other families may emphasise language abilities and may promote reading and storytelling at home, while not worrying too much about the child’s practical skills like competent shoe-cleaning. There will always be things about the child’s background that you may not know, so stay flexible and respectful and be willing to get to know the child slowly.

Being sensitive to

disability

Not

only culture, but also ability (or disability) may be a source of

discrimination at the ECD centre. More and more children with physical disabilities

are being integrated into mainstream classrooms as this provides good learning

opportunities for both the disabled child and his or her peers. Your ECD centre

may already include a child who has sight or hearing impairment or who is

physically disabled in some other way. The children’s acceptance of the

disabled child depends on your own acceptance and the atmosphere created by

your management of their special needs.

1.2.3 Ensure that the facilitation approach takes advantage of teachable moments

When facilitating an ECD session, you need to ensure that the facilitation approach takes advantage of teachable moments:

- “Teachable moments†refer to those unplanned opportunities for development that present themselves during the daily programme or routine if child is cared for at home by a parent figure.

Being a sensitive practitioner means having knowledge of the background and culture of each child and respecting it when interacting with her. This means always being careful not to use discriminatory language, or slang or culturally biased remarks, to keeping in mind that the culture of the class room may not match the home culture of the child. The gap between home culture and class culture may make it difficult for the child to perform tasks at the appropriate developmental level, because of language difficulties or attitudes to tasks.

Some cultures do not emphasise individualism and independence in the way that the western urban culture does, so a child from a more culturally focused background may struggle to perform tasks alone at first. Always be aware that there may be things about the child’s background which you may not know and be willing to learn about these over time or visit the child’s home in order to get to know the child better.

Suggested strategies for keeping teaching bias–free and for using teachable moments to reinforce the acceptance of diverse cultures:

Step 1: Encouraging awareness

Practitioners

should meet once a month to develop anti-bias awareness and knowledge. The

kinds of questions practitioners should be asking themselves are, “How

did I become aware of the various aspects of my identity? What differences

among people make me feel uncomfortable? When did I experience or witnessed

bias in my life and how did I respond? ‘Group members should work towards

facing bias and discomfort and eliminating their influence in teaching.

Children are also a good source of ideas about how to deal with diversity.

Practitioners can ask the children questions like “What do you know about Indian children? What makes you a boy or girl? What kind of work could this person do?†You do this while showing them a picture of a person in a wheel chair. The child’s answer will show where there are points of discomfort. The practitioner can then review the activities and plan to work constructively and sensitively around those issues, building known knowledge and acceptance of the culture which might be perceived as strange or threatening to the child. Practitioners must look critically at the learning resources in the classroom, to find out which materials may be giving a culturally-packed message. For example, a puzzle which shows a female teacher and a black male truck driver may seem at first to promote women in the role of teachers, but seems to imply that black people do manual work while whites do educated work. It is important to have a variety of images showing men, women, different cultures and ethnic groups in all sorts of combinations. It may be necessary to buy new materials that are not stereotypical.

It is important to discuss with parents what contribution they might want to make to the classroom environment to make it more representative of everyone’s culture. Their inclusion will also have a positive effect on the children’s perception of the classroom being a safe extension of the familiar culture of home.

Step 2: Engaging with children and parents:

In the second step, you begin to apply your

understanding, and awareness of issues of bias, and to engage with the children

and their parents.

Derman explains that an event in the class may provide a teachable moment in which the children may be receptive to understanding why we should be compassionate and accepting of others whom we see as different from ourselves.

For example, a new child who is an albino, or a child who wears a hand band (Isiphandla) or a child with a burn scar on her face, may provoke a lot of questions from the children.

You may find it difficult to deal with this when it happens, but your thinking and preparation in the first step should have provided you with some resources. It is important not to brush off the children’s questions but to answer them as honestly and compassionately as possible.

To deal with gender issues, it may be helpful to invite visitors whose activities and roles are counter to stereotypes, or go on visits to workplaces where gender roles are not prescribed. It is also helpful to read books about children doing non-traditional activities, but experience is the most valuable way to show that gender roles can be flexible.

Draw the parents into participation to your anti-bias activities. Share information with parents’ mornings/evenings and in newsletters. Schedule an educational evening for parents about how children develop identity and attitudes. Parents and caregivers at home can also be encouraged to recognise teachable moments and cues given by their children, and respond appropriately to deal with anti-bias issues as well as general developmental skills. At the same time you should keep your own staff support group going to maintain awareness and evaluate progress of the anti-bias work and to develop your own personal growth on these issues.

Step 3: Integration of anti-bias perspective

In

this step, the issues of inclusiveness and diversity are familiar territory and

naturally included in the curriculum and in your approach. As the children

engage in activities, they respond with comments and questions that become

further teachable moments. These teachable moments’provide points for new

activities to be developed.

Teachable moments are useful as they are a rich opportunity for the child to steer the learning process and content according to her developmental needs and individual preferences. For you they are a challenge to respond with creativity, compassion, knowledge, intuition and enthusiasm as you engage with the child in learning something vital and relevant to her development, her culture and her individual growth. Children provide cues to signal teachable moments, and your responsiveness and full attention should make them valuable learning experiences, not only about inclusiveness but about anything that is meaningful to the child.

1.3 Identify activities to support the development of babies, toddlers and young children

Each age has specific developmental needs, so we need to adapt the ECD classroom and resources to suit the activities. In choosing which resources to provide, it is important to consider whether they are appropriate for the specific developmental ages of the children in your care. If the activity is too difficult for them, they will feel frustrated and discouraged. They may lose confidence in their ability to tackle that kind of challenge for a long time to come. On the other hand, if it is too easy, they will lose interest and become bored. You therefore need to maintain a balance between giving the children a sense of achievement and control, and at the same time stimulating them to learn new things and extend their skills.

How play aids development

“Play is key to every child’s well-being. Children

learn about the world and experience life through play. One definition of play

is “the spontaneous activity of children.†Through play, children practise the

roles they will play later in life. Play has many functions. It increases peer

relationships, releases tensions, advances intellectual development, increases

exploration, and increases chances of children speaking and interacting with

each other.– Mary F. Longo

1.3.1 Ensure that facilitation uses developmentally appropriate

activities

When

facilitating an ECD session, you need to ensure that you use developmentally

appropriate activities that are fun, relevant and meaningful to the life-world

of the children, within the context of your daily and/or weekly programme.

The developmental appropriate activities that you use during facilitation in a daily and/or weekly programme, need to be fun, relevant and meaningful to the life-world of the children.

Age-appropriate programmes

We

can all agree that children at different ages and stages of development have

different needs. We cannot have the same expectations of a five month old baby

as we do of a three year old child. In order for children to feel happy, secure

and supported, we need to cater to their needs. The various theorists such as

Piaget, Erikson and Vygotsky studied particular areas of interest but there are

overlaps. The major point of agreement, though, is that play is a means of learning.

“To re-enforce learning, we always apply the skill we have learned, hence we learn by doing.â€

No matter the age of the child, your daily planning needs to include time for the child to play freely and spend time exploring his/her environment in order to learn.

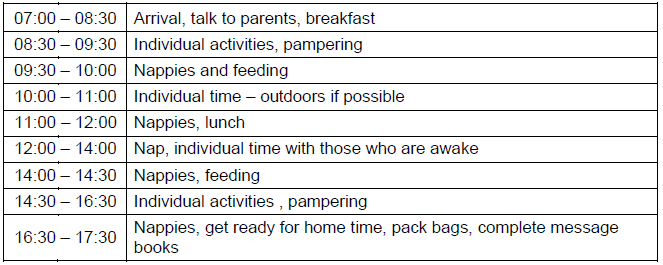

Suitable daily programme

The

programmes below are suggestions and ECD centres may differ in their

implementation of activity schedules. It is vitally important to cater to the

needs of the various age groups, taking into account their particular

developmental needs and abilities.

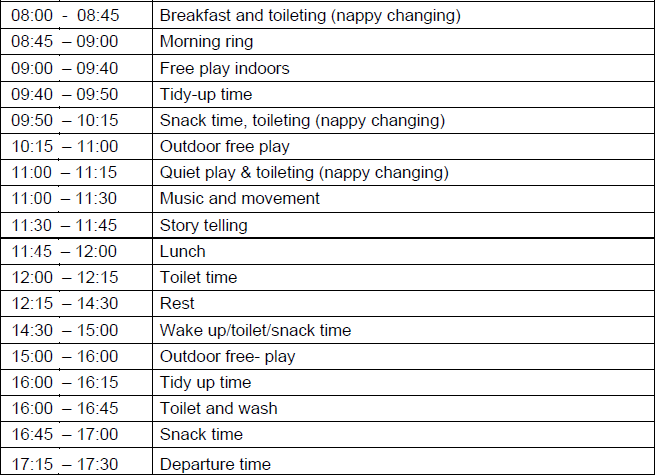

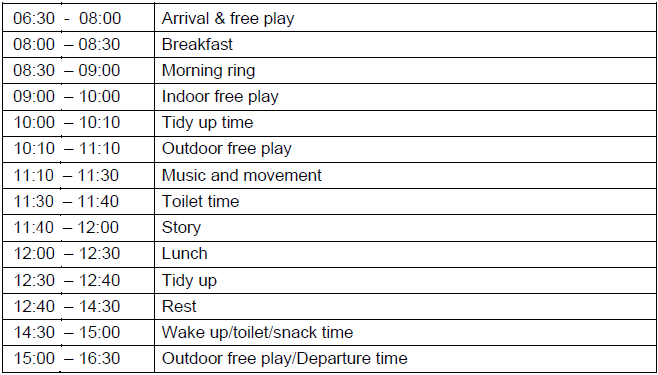

Daily programme for toddlers (6 – 18 months)

Daily programme for toddlers (18–30 months)

- Toddlers need a variety of play experiences

- They need lots of language input in the form of rhymes, songs and stories

- Remember they may still have individual sleep needs/times

- Still need individual attention as they are still at parallel play stage.

Daily programme for

young children (3 – 4 years)

- Young children need lots of variety and time for individual as well as group activities.

Many ECD centres plan their daily and weekly activities around weekly themes such as the seasons, transport, families, insects, the sea, wild animals, pets, sports, the dentist, musical instruments, holidays, and so on.

1.3.2 Identify activity purposes and ensure that they are consistent with given frameworks, guidelines and/or plans

- The developmental outcomes can be further broken down into goals for each particular activity that you present or provide in the class

- Physical development includes fine motor, gross motor, balance and rhythm

- Cognitive development includes concept development, thinking, reasoning, problem solving, counting, and predicting as well as emergent literacy and numeracy skills

- Language development includes vocabulary-building through listening and speaking and non-verbal language such as gestures

- Social and emotional development includes self-concept and identity, independence, affection, dealing with conflict, pro-social behaviour, accepting authority and empathy

- Creative and imaginative development includes imaginative play skills, expressing ideas, curiosity and a desire for knowledge

- Moral development includes values such as sharing, kindness, knowing right from wrong, acceptance of discipline and rules

- These goals are often integrated as they cannot be separated and are closely linked and related. One activity may cover many of the goals above – either by design or accidentally.

You may set up an art activity that focuses on drawing with crayons. This most obviously covers fine motor and creative skills. However, as the children are engaged in the activity:

- They discuss the colours they are using

- Take turns to use the favourite red crayon

- They talk about what they are drawing.

The activity will thus cover cognitive, language, social and emotional as well as imaginative development.

Think about how an activity, such as drawing with crayons, can stimulate more than one area of development.

1.3.3 Ensure that identified activities are

appropriate to the given context and support the developmental outcomes

As we

said above, each age has specific developmental needs. Therefore we need to

adapt the ECD classroom and resources to suit the activities.

Babies

They will sleep, eat,

play and have nappies changed in one room:

- Cots with bedding and mobiles

- Nappy changing area that is hygienic and safe

- Storage for bags, personal belongings

- Large mat area with space to crawl and play with toys (must be able to be cleaned regularly)

- Toys, balls, cloth/plastic or board books that have bright and bold pictures and different textures

- Area for messy play/eating area that is tiled

- Cushions, mattresses

- Safe flat, grassed outdoor area with baby swings

a) Supports a young child’s physical development. Cognitive development, language development, social and emotional development, creative and imaginative development, and moral development

b) Do you think this is a suitable activity for young children? Explain your answer.

Figure: A mobile is an example of a resource that is suitable or babies

Toddlers

They

will need a sleeping and nappy area but also close proximity to toilets for

toilet training.

In addition, they will need:

- Mattresses for sleeping

- Storage for bags, personal belongings

- Mat area for group activities like morning ring, story and music or movement

- Classroom can be divided into basic areas – creative activities, books, toys, blocks and house corner

- Suitably sized tables and chairs for eating and creative activities

- Outdoors they need low jungle gyms and slides, tricycles or pushbikes and sand and water play resources.

Figure: Young children and toddlers need suitably sized tables and chair for creative activities

Adventure play: includes boxes, sheets and other movable items that children can use imaginatively in the garden. Equates to fantasy area inside.

Movement exploration: includes obstacle courses, balance beams, tyres, bats, ball etc., which allow children to handle objects and develop both gross and fine motor skills.

Also, remember that within any group of children of the same age, there will be some who are many months older than others, and six months at this stage of a child’s life can make a very big difference to what a child can do.

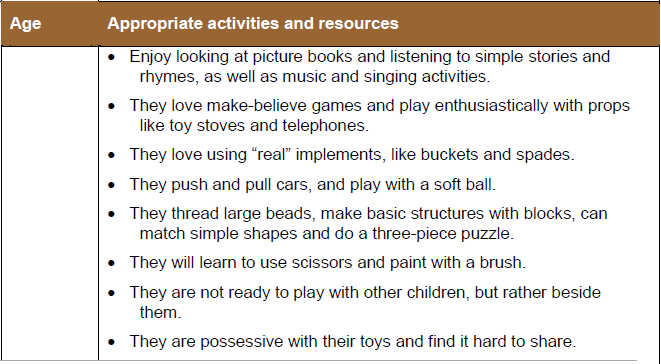

The table below outlines which specific learning resources are appropriate for children at each age from birth to five. It is very important to bear in mind that this is a general guide only – every child is unique and each one has a different personal timetable of development. Often a child will be advanced in one area, but less so in another, for example, one child has an outstanding vocabulary and advanced reading skills, but doesn’t manage well with gross motor activities; another is socially confident but is behind in cognitive activities. You have to be aware of their individual needs, and provide them with resources that will allow them to enjoy their strengths, as well as ones that will gently develop their weaknesses.

Appropriate learning resources according to age

It is very important to remember that your role as the ECD practitioner is to facilitate learning. This does not only imply that you lead children in activities, but that the environment that you provide stimulates learning in the child. You need to be able to plan the areas, organise and oversee activities, communicate concepts and ideas to the children, manage behaviour and assess needs on an ongoing basis so that you can adjust the environment accordingly. In this way you will encourage active play as the children will use all their senses in learning.

An ECD classroom that remains stagnant will not provide opportunities for self-discovery and leads to unhappy, frustrated children who develop bad behaviour patterns from boredom. By keeping children interested and stimulated through a combination of familiar and new activities and games, you will nurture their love of learning.