Unit 4 Online Study Guide

Learning Unit 4: Facilitate the development of babies, toddlers and young children

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to facilitate the development of babies, toddlers and/or young children, and use communication effectively during facilitation. You will be able to:

- Manage children in a manner that promotes development and is sensitive to the needs of individual children

- Carry out facilitation in a manner that ensures the physical and emotional safety, security and comfort of the children

- Carry out facilitation in such a way that behaviour and life-skills are modelled in a developmentally appropriate manner

- Ensure that facilitation assures the holistic development of children

- Ensure that communication is responsive and promotes development

- Ensure that verbal and non-verbal interactions are developmental

- Use appropriate behaviour and conflict management.

Facilitate the development of babies, toddlers and young children

Facilitation

that promotes the holistic development of babies, toddlers and young children

should be characterised by nurturing warmth. By having a nurturing and

emotionally warm tone in your approach to the children, you provide a solid foundation

for their sense of security and self-acceptance. In such a climate of warmth the

child feels free to play, explore, make mistakes and try again without fear of

failure. Their self-image grows, they feel respected, can show initiative and

try out new ideas and feel free to express their opinions.

4.1 Manage children in a manner that promotes development

Does

nurturing mean there are no rules and limits? No, the opposite is true – the

child experiences being cared for by having rules and limits too, as they

provide structure, fairness, and containment (control). But

the warm and caring attitude should come first, and the rules should be fitted

into that, so that the child feels heard and understood and that his or her needs

are being met. They then feels no anxiety about obeying a set of rules. The

warm atmosphere allows children to succeed as they have a sense of inner

security, and can do well at their particular level of skill.

Here are three ways in which you can become more of a nurturer:

1. Stay positive in responding to children

Keep

a positive frame of mind for yourself and your learners. Respond consistently,

notice their positive qualities, encourage the learners to stay positive too

and start the day with a positive or caring greeting or message for each child.

They will absorb and learn your positive attitude. Avoid saying “No, that’s the

wrong wayâ€; rather simply encourage and show them again the right way: “See if

you can do it this way next timeâ€.

2. Tune in and observe

Focus

on the child’s unique qualities, strengths and capabilities, and respond with

acknowledgement, praise and encouragement. Review each child’s well-being at

specific points during the programme. For example, you could think back about

the morning during snack time, and get a sense of how different children are

coping with the demands of the programme or peer interaction. Listen whenever

you can, ans pay attention to their free play or chatter. In this way you will

get in touch with the child’s mood and general well-being and have an

opportunity to notice anything that may need your attention and support. (You

will also learn to make observational notes about this tuning in.)

3. Take every opportunity to give positive

attention

Always

look for ways to encourage and be warm about any effort the children make, even

if there is no effort – the children just want the sunshine of your love! Even

if your style is not usually so jolly or outspoken, you can learn to pay

attention first, and then to increase the warmth of that attention by degrees.

Do this by reminding yourself of anyone who has been a caring or inspiring

person in your own life. By being more nurturing, you do half the work of

facilitating. And if you improve the child’s self-image and build

self-confidence, you make it possible for the child to tackle developmental

tasks with freedom and confidence.

4.1.1 Manage children in

a manner that is sensitive to the needs of individual children

Since

all the domains of development are linked, you can promote development in all

domains by presenting them in a nurturing and warm way to establish the child’s

sense of security and acceptance. This provides a background of empowerment,

trust and freedom which allows the child to play, experiment, be him/herself

and make mistakes without fear. Research has shown that a nurturing environment

enhances and improves self-image in the following ways:

- Children perceive a sense of warmth and love

- They are offered a degree of security, allowed to grow and afforded the opportunity to try new things without fear of failure

- They are respected as individuals

- They are encouraged to develop initiative and new ideas

- They are encouraged to express their opinions.

Nurtured (cherished) children recognise that there are clear and definite limits within the environment, that there are rules and standards that are reasonably, fairly and consistently enforced. This gives them a sense of what is allowed and a sense of where they fit into those boundaries. When they feel that they are heard and understood they can more easily accept the rules for behaviour, as their needs are being met. Most important, perhaps, is that nurtured children have a chance to succeed at their particular level of accomplishment.

4.2 Carry out

facilitation in a manner that ensures the physical and emotional safety,

security and comfort of the children

When

facilitating an ECD session, you should carry out the facilitation in a manner

that ensures the physical and emotional safety, security and comfort of the

children.

How can the ECD practitioner be more nurturing? Here are a few ways in which you can become more of a nurturer:

- Build self-esteem

- Be aware of the vulnerable child

- Cultivate a positive attitude

- Be observant

- Be prepared to give approval and positive attention.

Building self-esteem

Self-esteem

is the essential ingredient in human beings that increases personal growth,

happiness and development on all levels.

By showing warmth, respect, responsiveness and sensitivity to the individual child, their context and their needs, the facilitator can promote the development of the children in his or her care. The facilitator’s warm and caring attitude is the “fertiliser†that grows the child’s self-esteem.

Be aware of the vulnerable child

Think of the child as a vulnerable plant that will

bend and wilt if it hears unkind words. Try to speak kindly at all times. If

you must raise your voice, do it only occasionally – think how much you dislike

it when you have been shouted at in the past. Show warmth in the way you speak,

use a bit of humour to show you are understanding, and avoid using negative

terms such as “Don’t hesitate!†“Don’t be stupid!†“Can’t you understand?†or

labels and judgements like “You’re so clumsy!â€. Show tolerance, patience and

kindness in all your behaviours, and the children will learn to communicate in

the same way.

Cultivate a positive attitude

You can best help children to feel good about

themselves by being consistent and having a good attitude yourself, especially

about children’s positive qualities. Make a conscious effort every day to make

your children aware of their positive attributes. Every day, remind yourself of

how important it is to say something positive.

If you are working with younger children, start the day by deliberately greeting each child with a caring statement, even if it is as basic as telling the child that you like the way in which he/she said good morning! Remember that your talk becomes their inner self talk. Consistency is very important; make a conscious effort every day to help the children develop positive feelings about themselves.

Be observant

Whether the child feels loved or unloved has a big

effect on his or her development. To foster a child’s positive self-image, you

must notice and comment on the child’s unique qualities, strengths and

capabilities. Any desirable trait of behaviour, act of thoughtfulness, display

of creativity or special effort should be noted and acknowledged. The ECD

practitioner should, therefore, work hard to be observant, by mentally noting

children’s behaviour and characteristics. During the day you should have a

quick check-in scan of each child at least three times during your programme,

to get a sense of how that child is coping with the day’s challenges. Do this

by looking at the child and listening to any interaction or free play. This

allows you to tune into the child’s mood and general well-being and to notice

anything different that may need your attention and support.

Be prepared to give approval and positive attention

Three- and four-year-olds believe parents and other

adults are super human beings – they can even see through drawn curtains! The

child accepts that these “all powerful gods†treat me as I deserve. What they

say is what I am. All a child really wants and needs are your approval and

positive attention. Do not neglect to provide these things.

As an ECD practitioner you can learn to be a nurturer (carer) to provide an environment that enhances and improves a child’s self-image.

4.3 Carry out facilitation such that behaviour and life-skills are

modelled

In

most case children learn what they see powerful or loved people doing. The most

important person to the child is you, the classmates and teacher and her

parents and siblings and friends. Your role as a practitioner is to engage with

the child deliberately in order to encourage and promote her development. Her

learning from you takes place not only because of the things that you do but

also because of how significant you are and how that affects her motivation to

learn.

Children learn and imitate behaviour they have observed in other people. There are certain conditions for social learning to take place:

- The child has to be paying attention

- Once the child has seen the behaviour it can be remembered and practised and improved

- If the child is motivated, the social learning progress will be successful and the child will imitate the behaviour.

Life skills are the social skills which humans use to manage their own lives and their relationships with others.

Modelling is the word used to describe the social learning that takes place when the child or observer identifies with a role model and unconsciously copies her or shapes his or her own behaviour to fit that of the model. “Modelling†here refers to the way in which the facilitator provides an example to the children concerning behaviour.

4.4 Ensure that facilitation assures the holistic development of

children

Not only are you educating through the activities you

are presenting, but you are also communicating knowledge, values, attitudes,

life skills and physical habits simply by being in the presence of children.

Attending and problem-solving

- Every activity you present to the children shows that you are attending to them and to the activity. Your concentration, enjoyment of the activity, willingness to admit that you may not know everything and make mistakes sometimes, are all good qualities that the children will see and absorb

- Your focus of attention when helping a child with a puzzle or with cleaning up after an art session, demonstrates how to get the job done, and how to solve problems through perseverance and effort

- Attending and problem-solving are core behaviours in all learning and by modelling them, you set a good example for the children to follow and succeed at their own learning.

The other valuable skills which you model for the children can broadly be called, “life skills‟. Life Skills include:

- Managing the self (care for the self and knowledge of the self); managing relationships with others (family and friends), and managing one’s relationship with society

- To the child, the caregiver represents the outside world. The important skill which the children will learn from you by modelling, are cooperation and competition, conflict solving, building and keeping friendships, managing relationships with sincerity, sharing and loyalty. You are an example for the children to follow.

Care for the self

The basic building block of relationships is the

relationship to the self. Your relationship to yourself provides you with the

vehicle which carries you through your life, and it affects your work as an ECD

facilitator. The following guidelines for a healthy relationship with yourself

will also have an effect on everyone around you:

- Accept yourself

- Be friends with your body and treat it kindly

- Trust your intuition

- Allow feelings their appropriate place and time

- Comfort and reward yourself with the things that are familiar from your culture or religion or experience, to support yourself through tough times

- Do not make judgments about yourself or others but take responsibility for the results of your actions and take corrective action if needed

- Take physical care of yourself. Your clean hands and nails, clean clothes and fresh smile are reassuring to the children and show that you respect them as social beings. Teaching the children hygiene (hand washing, face washing) and noticing when they need their nails cut, or telling them to keep their hair out of their eyes with a hairclip while they play, will have no impact if your own nails are dirty and your own hair is hanging in front of your eyes.

Relating to others

In interacting with a baby, singing or talking to him

or her, you show caring behaviour that any observer (another baby or child in

the room, or a colleague passing by) will see and remember. In all your

relationships, observers learn about your values from your behaviour and

communication.

Why is holistic

facilitation important?

These

interrelated areas of development all continue to develop while the child is in

your care. With your knowledge of child development, your commitment to

children’s rights and needs, and your personal values of caring and nurturing,

you can successfully guide the child to experience all aspects of herself as

equally valuable and important. If you don’t do this, part of his/her ability may

easily be neglected or part of his/her emotional development delayed or

discouraged.

How to facilitate in a

way that promotes holistic development

Holistic

development can be achieved through interactive play, storytelling, listening

to music, discussing feelings, drama and role play. Children also need to be

exposed to a variety of resources that they can explore in a variety of ways.

Children need to be treated as special. When you plan your ECD programme you must take the children’s individual learning needs into account.

Children learn best when they do and see, and when they can play freely, explore, discover and solve problems.

Holistic learning happens when learning areas are combined, for example teaching about water at a stream, using containers catching and releasing tadpoles, listening to stories about water like Noah’s Ark, learning a water song.

4.5 Ensure that

communication is responsive and promotes development

Young

children do not have the language, communication and emotional skills that are

necessary to express their thoughts and feelings, ideas and concerns. Language

activities such as storytelling, rhymes and songs stimulate vocabulary and

understanding of language so that they can begin to express their inner and

outer worlds. When you talk to them, you encourage them to begin to verbalise

their own thoughts, feelings and ideas. In this way, they become better at

expressing the feelings and ideas through using language. You should make an

effort to use your talking and listening skills, the two components of your

communication, to promote the children’s language development.

Overview aspects for discussion:

Your own communication

- Listen to the children

- Respond with questions

- Ask leading questions

- Ask open-ended questions

The children’s communication:

- Their communication about experiences

- Their conversation with friends

Communication through activities:

- Group time

- Communication as a component of all activities

- Stories

- Praise and feedback

Listen to the children

Listening

is probably one of the most important skills an ECD practitioner must develop.

To foster good language skills, children must be allowed to say what they mean

and be given the time to say it. It is very important for the practitioner to

listen to what children say, and to respond to their messages.

Praise and feedback

Children

feel encouraged and motivated when their creative efforts are discussed and

praised; however, children can easily see through superficial or insincere

praise. Avoid comments like these ones:

- You’re a clever girl!

- That’s the best hand print I’ve ever seen!

- You’re going to be a star when you grow up!

Using appropriate

questioning techniques

If

you as facilitator respond with interest, use attentive questions that show you

have listened and understood what the child has said, use leading questions to

expand the topic or extend the opportunity for conversation, you build upon

what the child has to offer. These are examples of how to communicate

responsibly to promote development. It expands the communication for the child

and provides recognised stimulation which promotes better understanding and

social skills.

Ask leading questions

Leading

questions are questions that provide direction or guidance. Here are some examples:

- What do you think will happen if you mix blue paint and red paint together?

- What does the rabbit think about when everyone goes home for the day?

- Why do the blocks fall over when you put the big ones on top of the little ones?

You can get children to participate out by asking them leading questions and asking for clarification. Children will not develop good language and communication skills if they are never asked to think and use their imagination to picture themselves in a situation.

Ask open-ended questions

Open-ended questions are questions that have no right

answers. Some examples are:

- What would you like to take on the picnic?

- How do you feel when it rains?

Open-ended questions will help children to draw their own conclusions using their observations and cognitive and imaginative skills. Such questions give children a chance to express their very own answers without worrying about whether they’re right or wrong. This keeps a positive atmosphere in a learning situation, as any answer is accepted as a good enough contribution and the child finds it rewarding to participate.

You will have many opportunities for conversation with children when they arrive at the school, when they need help in the bathroom or during lunch. Take advantage of these moments to help children communicate. Ask them how things are going at home or how their pet is. Keep the tone of your interest light and positive, not inquisitive or negative. Let them tell you about what their brother or sister did at lunch time. These are very special moments that not only foster (promote) language development but also make a child feel special and secure. Bending down to a child’s eye level will also give the message that you respect him/her and want to listen. Your responses should focus on both the message and the feeling, or tone, to give the child the sense of being heard.

The children will benefit from the communication in every activity. For example, they may need to listen to a story and create a picture inspired by the story. They may need to talk and work with a partner. They may need to take turns to communicate in a large group. As these examples show, every learning activity that children do will require them to talk, listen and communicate. In this way they develop their communication skills in an integrated way. Your responsiveness lies in providing these opportunities that the children need, to build their communication skills and understanding, thereby promoting their holistic development.

Stories

Stories that you tell and stories from books, all

increase the variety of responses you can offer the children in your care.

Stories are a tool to identify the children’s own concerns, fears and

experiences. One way to do this is by asking questions when using an

illustrated book: “Look, the puppy has run away. Has anyone here had a pet that

ran away?†Or, “Thandi is afraid of having an operation, has anyone here had an

operation? How did you feel about it?â€

Remember, children can relate to books by making the pictures, words and themes apply to their own lives. This does not mean that the books we choose have to replicate (be a copy of) our learners’lives. For example, children may be interested to read a story set in another country, like India. You can relate this story to the children’s lives too:

“Terry is lost. She is crying. What do you think she is feeling? Have you ever been lost? How did you feel?â€

We can also use books and stories to help children to become more aware of their emotions and give them the vocabulary to express how they are feeling. There are many books for young children that deal with specific issues. These books are very useful to help children to come to terms with difficult situations (for example divorce, death, fear of the dark and adoption). When we deal with difficult issues, we usually have to confront strong emotions like death, sadness, bullying fear, divorce or anger. Therefore, issues-based books and stories may also raise the subject of how to deal with feelings like anger, jealousy, fear and joy. By seeing how the characters in the story coped with their strong feelings, children can learn to deal with their own emotions. Your role as a practitioner is to steer carefully through strong emotions, accepting whatever the child would like to express, and responding with empathy and warmth.

4.5.1 Respond in a

manner to show a clearly developed understanding of complex issues under

discussion

Effective

communication only takes place when the reaction of the receiving person is

positive, according to the expectations of the sender. For example, by altering

the intonation of the voice a customer may either receive the message that a

waiter is really pleased to see and serve him or that he is merely another

nuisance demanding to be served.

Effective internal and external verbal communication has a direct effect on a company’s image and success in the following ways:

- Good, clear, concise communication eliminates time wastage in trying to resolve confusion, errors and conflicts

- Customers/guests/patrons like feeling important and will return and recommend the establishment to others if they are treated with politeness and helpfulness.

This often results in returning customers and more business. If staff members display positive attitudes and speak to each other with respect, they reflect a positive company image. This results in customer having confidence in the establishment.

Types of verbal communication

Internal

Internal verbal

communication may be categorised as follows:

- Intra-personal communication is communication with oneself. Talking to oneself is an example

- Extra-personal communication (as illustrated above) refers to communication to an inanimate object or non-human (plant or animal).

Interpersonal communication refers to an ordinary conversation on a one-on-one basis, or a very small group. It may also refer to communication between groups of individuals (group discussions or informally in a crowd).

In general, as the size of the organisation increases, communication decreases and morale declines. The ever-increasing size of organisations means that lines of communication are further and further extended.

The more communication “centres†(e.g. departments within an organisation) a message has to pass through, the greater the chance of distortion (misrepresentation) or breakdown in communication.

Instead of trying to improve communication abilities of all employees, there are steps that may be taken to alleviate the situation:

- Establish open channels for feedback

- Lay down policies and procedures for communication

- Top management should communicate directly to all staff members using the public address system or public notice boards.

External

This refers to

communication with an audience or people outside of an organisation.

When people are communicating face-to-face, body language plays a vital role to convey the appropriate messages.

4.5.2 Identify

characteristics of a speaker’s style and tone that attract or alienate an

audience

In the business culture, it is imperative (essential)

that you make eye contact if you want to make a positive impression on guests

and maintain a relationship that is based on trust. Consider the following:

- Maintain eye contact without staring, as this is arrogant and threatening

- Avoid blinking too much as this communicates nervousness and can be interpreted as an indication of dishonesty

- Try to keep eye level on the same level as the guest. Stand if the guest is standing. If the guest is seated, accommodate this by standing back a little.

Facial expressions

Be

aware of facial expressions when you speak to people. Professional service

providers (e.g consultants or training providers) who deliver excellent service

have alert, lively and appropriate facial expressions.

Avoid the following facial expressions:

- An expressionless or deadpan face that shows no emotion in response to what guests say makes them feel uncomfortable. This may be interpreted as boredom, rudeness or indifference

- An arrogant or stern (strict) expression creates the impression of being superior to others

- Grinning continually makes one look stupid. It creates the impression that the person does not understand what is being said or done. It may also create the impression of being deliberately unhelpful or even spiteful.

Gestures

Head and hand movements (gestures)

often accompany speech:

- Smooth and wide gestures with the palms facing upwards are seen as warm and welcoming. People react positively to friendliness and helpfulness. Guests are naturally drawn to people who use calming gestures

- Sharp, short gestures with the palms facing downwards, are aggressive and negative

- People react by wanting to enter into or avoid disputes. When you are upset or if there is a need to discuss problems, you should make an effort to control your gestures. Problems are never resolved through aggressive gestures.

Posture

The way the speaker

stands, sits or walks, indicates a great deal about the speaker’s attitude,

mood and self-esteem.

A correct posture entails the following:

- Stand upright with your arms comfortably at your sides

- Keep shoulders dropped and slightly back

- Stand with feet slightly apart to maintain balance

- Walk briskly because it creates a professional impression

- Sit upright with shoulders back. Slouching creates an impression of laziness

- When speaking to guests either face them or turn the body slightly sideways towards them

- Do not lean against walls or furniture

- Do not fold your arms – they create the impression of being shy or arrogant

- Standing with hands on hips creates an impression of arrogance

- Swinging when speaking to people suggests a lack of self-confidence

- Resting the face on hands while leaning on counters makes one appear lazy.

Personal space

This

refers to the space each person has around him/her and into which intrusions (invasions)

are unwelcome. The exact size of the area around each person differs and

depends on a variety of factors including, personality, culture, family

background and even the type of sport played.

Shy people usually need a wider personal space than outgoing people do. People instinctively indicate when their space is invaded - they either move away slightly, look uncomfortable, blink their eyes to show their discomfort, or look behind the speaker to avoid eye contact.

4.5.3 Identify and

challenge the underlying assumptions, points of view and subtexts

A person’s

point of view is his/her manner of

viewing things and describes an attitude or a position from which something is

observed or considered. Your point of view is also referred to as your

standpoint and reflects your attitude or outlook on events.

Subtext refers to the content underneath the spoken dialogue. Under dialogue, there can be conflict, anger, competition, pride, showing off, or other implicit ideas and emotions. Subtext refers to the unspoken thoughts and motives of participants in a conversation - what they really think and believe. Subtext just beneath the surface of dialogue makes life interesting, but it can also cause people to be and feel misunderstood.

An underlying assumption is something you believe to be fact, and therefore you base whatever follows on that underlying assumption.

4.6 Ensure that verbal and non-verbal interactions are developmental

Language helps us to make ourselves understood through

using a united system of words. We take our language for granted until we

suddenly cannot find the right words to explain ourselves, or when someone asks

us to explain what we mean.

Have you ever tried explaining yourself to someone who is not a first language speaker of your language? It is much easier to be misunderstood in those circumstances. Even when you are not speaking loudly, you are using language to think and create meaning. We call this intra-personal communication. Interpersonal communication happens between you and others, and intra-personal communication happens within yourself. Speech and language includes but is not limited to:

- Verbal or spoken communication

- Written communication

- Art, e.g. poetry, music, literature

Non-verbal

The

term “non-verbal communication†is used when we refer to communication that is

not written or spoken. Researchers have found that when we interact with each

other, we interpret more meaning through non-verbal behaviour than through the

verbal message. In fact, they claim that as much as 65% of the meaning is

understood though non-verbal communication.

Body movement, posture and gestures

Body movements are strong indicators of how you feel. You can tell how

your boss is feeling sometimes just by the way she is walking! Some people walk

as if they are in a daze (research tell us that those are the ones who are

likely to get mugged first – they are communicating: “come and get me!â€),

others walk with purpose. Sometimes you can see if a person is feeling dejected

(sad) by the way they walk.

Your posture can also communicate a lot about your personality, your status, how you are feeling today, your self-image, and your gender. Have you ever noticed how a tall person who is uncomfortable with being tall may slouch their shoulders, whilst some 6-foot models “strut their stuff†on the catwalk? Do you see how this shows a difference in their self-image? But remember, a slouch may just be a temporary indication of a person’s emotional state for the day – perhaps they only feel dejected now, and will bounce back when they have overcome their particular emotional hurdle. We must be careful not to generalise our interpretations.

Gestures are movements of the hands, arms, legs and feet. Hand gestures generally describe or emphasise verbal descriptions or communicate attitudes.

Facial expressions and

eye contact

Facial expressions communicate how we are feeling and our reactions to

the messages we are receiving. These are generally the real sign to how

strongly we feel about the message we have received. Have you ever received

unwelcome news, and you did not want to show people your reaction, but your

face and eyes gave you away? After all it is said that “the eyes are the mirror

of the soulâ€.

The way we use our eyes is also a way of interpreting meaning. Who will be viewed as more confident?

(a) a public speaker who

does not look at her audience, or

(b) a public speaker who

looks up during her speech?

I am sure you answered (b). Sometimes if someone is not being truthful they cannot look you in the eye. Can you think of other instances when people do not maintain eye contact?

Perhaps you are aware that in some African cultures, it is respectful to drop your head when having a conversation with a superior. Or think of someone who is distracted or bored. They will find it very difficult to maintain eye contact if they are not concentrating on what you is saying or the presentation at hand. Share any additional ideas regarding eye contact with your fellow learners.

Use of space

People convey messages about themselves by using space. Consider for

example a new student who decides to sit either in the back or front of the

class, or a staff member who sits far from the head of a table or at the head

of a table during a meeting.

Most teachers will tell you that the mischief-makers mostly sit at the back of the class and the more serious students choose a position near the front.

Use of touch

Touch can also

communicate the nature of the relationship between people.

Touching behaviour is different for people of different cultures, and we also need to be very aware of what makes other people uncomfortable and what is inappropriate. Also find out what touching behaviour could be understood as sexual harassment.

Use of time

People

can use other people’s use of time to interpret messages. If someone phoned you

at 03:00, you would probably expect it to be bad news. Similarly if you do not

return a client’s call within a time frame that he thinks is appropriate, he

may interpret your non-verbal behaviour as an indication that you do not care

about his business. Time is often a reflection of status, the higher your

status, the more control you have over time. For example, the executives in

your organisation will control how long you will wait for an appointment.

Different cultures and personality types view time differently, often resulting

in misunderstanding. Organisations therefore need to have company standards for

time keeping that everyone adheres to.

Personal appearance

Personal appearance

includes the way you look, including but not limited to:

- The clothes you wear

- Your personal grooming

- The symbols you wear (badges, tattoos, etc.)

Your sense of style, etc. and can influence first impressions, job interviews, consumer buying behaviour and even courtroom decisions. Your personal appearance can give away clues about your age gender, identity, personality, attitudes, social standing, and income, to name but a few.

A job seeker looking for a position as a professional in a leading investments company who arrives for an interview wearing jeans and “tekkiesâ€, will probably not get the job, even if he has all the right qualifications and experience because the interviewer may interpret that the candidate is not professional.

What do the appearances of the people below communicate to you?

“One’s perception is one’s

realityâ€

The above saying means that even if someone else’s perception of you is incorrect or unfair, it is real to the person who perceives it. Our role is to manage other people’s perceptions of ourselves. We can do this by taking care of our physical appearance, without compromising our unique individuality.

Vocal qualities

In South Africa we have

a variety of accents and ways in which people speak.

This adds to the diversity of our nation and we do not want to make everyone a clone of the other. Only when our vocal qualities lead to miscommunication, do we need to work on refining it.

We need to use or vocal qualities to enhance the meaning of our message. Therefore we change our vocal qualities according to our situation:

Volume

Some people speak softer

or louder than others. We can increase or decrease the volume of our speech to

change our meaning. For example:.

- A client will use a louder voice to shout out his dissatisfaction at having his call transferred for a third time

- A soft voice would be used to show sympathy towards a client who has called in to enquire about benefits after her spouse has passed away

- You have to speak louder when you are interacting with a client if the air conditioning unit is faulty and making a noise

- Speaking too loudly in

inappropriate situations can be irritating, and interfere with meaning.

Speaking too softly can make it difficult for listeners to hear and understand

you.

Inflection

Inflection is the rise and fall of the voice. People

who do not use inflection in their voices have a monotonous “droneâ€. However,

overusing inflection can create childlike (“singingâ€) speech. You would

typically use more inflection when you are talking about something exciting.

Pitch

When interpreting emotions from the highness or

lowness of the voice, we can typically infer (conclude) a

range of emotions from calmness, cosines, lack of interest through to depression

from a low-pitched voice. A high pitch can indicate extreme emotions such as

fear or excitement.

Resonance

This is the quality and fullness of your voice, or how

pleasant or unpleasant your voice sounds to the listener.

Rate

Rate refers to the pace of your speech. Speaking

quickly usually indicates excitement, anger, volatility, whilst a slower speech

would indicate being relaxed, trying to make a point, depression, lack of

interest, etc.

Note: Speaking too quickly can cause your listeners not to hear all your words, and speaking too slowly can be monotonous and boring for your listeners.

Clarity

Clarity refers to the clearness of your pronunciation.

Your accent is acceptable, but only if the listener can understand what you are

saying.

A final note on vocal qualities (characteristics): For some of these vocal qualities the emotions indicated are very opposite for the same vocal characteristic.

4.7 Use appropriate behaviour and conflict management

Most

psychology books suggest that conflicts come from two sources: approach and

avoidance. To approach is to have a tendency to do something or to move in a

direction that will be pleasurable and satisfying. To avoid is to resist doing

something, perhaps because it will not be pleasurable or satisfying.

These two categories produce three kinds of conflicts:

- Approach-Approach Conflict – this is due to the pursuit of desirable but incompatible goals

- Approach-Avoidance Conflict – here is a desire both to do something and not to do it

- Avoidance-Avoidance Conflict – this indicates there are two alternatives, both of which may be unpleasant.

Other causes of conflict are:

- A lack of communication

- A lack of understanding

- Ambiguous (unclear) lines of authority

- Conflict of interest

- Disagreement on issues

- The need for agreement

- Generational of differences

- Religious disagreements

- Diverse perspectives

- Majoring in minors (this means paying too much attention to small details)

- Negative environment and dysfunctional relationships.

4.7.1 Language features and conventions can be manipulated

Language has certain

features and conventions which can be manipulated to suit different contexts,

audiences and purposes.

Conventions are the surface features of communication - the mechanics, usage, and sentence formation:

- Mechanics are the conventions and customs of written language, including spelling, punctuation, capitalisation, and paragraphs, which will affect the way you verbalise the content; for example, punctuation will determine how you say, “You did!†versus “You did?â€

- Usage refers to conventions of both written and spoken language that include word order, verb tense and subject-verb agreement

- Sentence formation refers to the structure of sentences, the way that phrases and clauses are used to form simple and complex sentences.

The physical nature of writing allows writers to craft and edit their sentences, combining and rearranging related ideas into a single, more compact sentence, but in oral language, words and sentences cannot be changed once they have been spoken. This places a great responsibility on the speaker to choose words carefully and plan verbal communications carefully.

Following conventions are a courtesy to the audience; it makes your writing easier to read or listen to by putting it in a form that the audience member expects and is comfortable with.

To use language features and conventions effectively in oral communication, you would therefore have to use your knowledge of the mechanics, usage and sentence formation correctly in order to ensure that you are communicating in a manner that suits the context, audience and purpose of the communication.

4.7.2 Ensure that

behaviour and conflict management is positive, sympathetic, constructive,

supportive, respectful and in line with current legislation

To manage children’s feelings, behaviour and

conflicts, you should have techniques that you can rely on.

Managing children’s

feelings

What can you do, as an ECD practitioner, to help

children learn how to recognise and deal with their feelings? Your task is to

help children develop the emotional skills so that they can manage their

feelings. These emotional skills won’t only help them while they are children.

The skills will also form the foundation of the emotional maturity they need

when they are teenagers and as adults.

What is allowed and what

is not?

In short: feelings are

allowed; socially unacceptable behaviour is not allowed.

Feelings can be managed by listening to them with attention and patience, acknowledging them, and naming them so that the child is clear about them. By offering your acknowledgement of the feelings (for example, “It sounds like you feel really sad and jealous of Leo’s new friend?â€) you make it possible for the child to clarify his feelings for himself. Again, don’t worry about anything else at this point, like whether you agree with the child’s behaviour or not. If you acknowledge the child’s feelings, this makes her feel safe while she struggles to manage them.

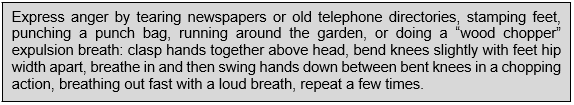

Feelings can be given an outlet that is more appropriate than the “acting out’ that the child may be doing. Provide safe expression for feelings by offering these safe ways as alternative outlets for intense feelings:

There are also other creative ways to express feelings: by using voices – singing, chanting, growling, whispering or using a nasty voice; through art activities like painting; and through stress management tools (examples follow in the next section).

Behaviour that is socially unacceptable, such as throwing toys in anger, should be limited. It is more constructive to do something with the feelings that will lead to a resolution, like expressing them safely and trying to fix relationships. Set limits for children to help them stop destructive actions and offer them an alternative outlet for the feelings. For example say, “I know you’re sad, but hiding here and chewing on a book is spoiling the book and that isn’t allowed. We could go to the bottom of the garden together and sit there behind the tree so that you can cry in private until you feel better. Maybe we could count the yellow butterflies when you have finished.â€

Stress management tools

You

can build stress-releasing exercises into your ECD programme to release the

build-up of unexpressed feelings and stresses. These techniques help to keep

the pot from boiling over, as their regular use will keep the children calmer

and better able to deal with everyday frustrations. Choose a few techniques,

demonstrate them once a week and use them as part of your response to cues

whenever tension is building. Do them as part of your intervention when the

children are struggling with feelings. Allow at least five minutes to do one of

these stress-busters:

- Slow breathing: Sitting cross-legged on the floor, or comfortably on a chair, take deep breaths, breathing in through the nose, out through the mouth, slowly. (This slows down the heart and has a calming effect.)

- Guided imagery: Get the children to lie down on their backs with eyes closed, and guide them through these images: “Let’s imagine … a beautiful field of green grass where you can lie on your back and look at the soft clouds floating in the sky; feel your body relaxing into the earth, getting heavier as you let go of all the feelingsâ€; OR “Imagine your heart glowing like a golden light with love, peace and quietness†(or similar guided imagery)

- Massage: Children sit in a circle for a massage, all facing left, so that they can massage each other’s backs gently and slowly; they could also use this circle to do a back tickle

- Floppy bodies: Stand and shake out hands, feet, shoulders, arms, legs, wiggle hips, shake head, shake out the feelings, and become all floppy

- Lie down straight with feet flopping to the side and

hands gently resting palms up. Begin

to relax your toes; when they are all relaxed, focus your attention on your

legs, imagine them relaxing completely… (and so on, progressing up to the top

of the head, and end with a deep breath in, and a stretch and breathe out).

These relaxation techniques are good for facilitators too.

Helping children manage

their feelings

It is

important that you demonstrate a process of dealing with feelings that show

that there is a beginning, a middle and an end to strong feelings.

- The first step is to check what you are modelling for the children – are you stressed, are your voice and your manner tense? You should be sharing appropriate feelings and showing appropriate ways of working through them, for example, “I’m sad that my dog died. Today I need to be a bit quiet and remember her; maybe I’ll feel a bit better tomorrow or the next day.†This will help the children to cope with their own feelings in a similar way.

Here are some other techniques you can use to help children learn to deal with their feelings constructively:

- Allow all feelings: don’t encourage “good feelings†or discourage “bad feelingsâ€

- Teach “feeling†words, like “angryâ€, “sadâ€, “jealousâ€, “happyâ€, “excitedâ€, “disappointedâ€, “lonelyâ€, to support children who are struggling with vocabulary (expressions) and with feelings. Use the issue books mentioned earlier as a starting point

- Help children accept, express and move through their feelings to a new point of understanding

- Remind children that feelings don’t last forever, that another day will come when they will feel a bit better.

It is slow work to focus on feelings, allow their expression, deal with the process of accepting and healing, but it is best to do this work carefully as it is an investment in teaching children to manage their feelings healthily for the future.

Acknowledge the child’s

feelings

Make sure you acknowledge the

child’s feelings, thereby allowing her to express them more clearly. Try not to

think about whether or not you agree with the child’s behaviour at this point.

Acknowledge the child’s feelings by saying, “You are really angry†or “You

looked sadâ€. “That must have hurtâ€. If you acknowledge the child’s feelings,

you tell the child that you care about her and support her. This will help to

make her feel brave and controlled while she still struggles to manage her

feelings.

Set limits to their behaviour

Redirect their feelings

There are many techniques you can use to help a child

redirect his feelings. Here are a few ideas:

- Express anger by tearing newspapers, stamping feet, punching a punch bag, running around the garden

- Express feelings by using voices – singing, chanting, growling, using a mean voice

- Express feelings through creative art activities. Say: “That’s a strong feeling. I wonder what colour it would be if you drew it. I wonder what that feeling would look likeâ€

- Express feelings by using a stress management tool. You’ll find out about these tools in the next lesson.

Managing stress

We

don’t always realise it, but children can suffer from stress. Often when

children are unable to manage their feelings, they bottle them up inside, which

cause body tension and stress. You can build stress-releasing exercises into

you ECD centre’s learning programme. Choose a few techniques and use them

regularly. Make sure you tell the children what these techniques are called.

Then when an individual child is struggling with feelings, you can give her

some time out by saying, “Phindi, take some deep breathsâ€â€˜ or “You look

frustrated - take a break and do the body shakeâ€.

Stress management techniques:

- Deep breaths

- Let’s imagine

- The massage train

- The back tickle

- The body shake

- Relax your toes, relax your nose.

Deep breaths

Tell

the children to breathe slowly and rhythmically in through the nose and out

through the mouth. It is helpful to some children if they close their eyes and

keep one hand resting on their heart area, monitoring their heartbeat, while

they take deep breaths. This exercise can slow down the heart rate and help the

children feel more relaxed.

Let’s imagine

Tell

the children to close their eyes. Then say, “Imagine you are at a beautiful

beach. The sun is shining overhead. Your body feels warm and happyâ€. Or say, “Remember

a time that you felt really happy. Try to make a picture in your head of that

time. Why are you feeling happy? What does the happy feeling feel like in your

body? ‘Give them enough time to create the mind picture in each step.

The message train

Get

the children to sit in a long queue. Then ask each child to place his/her hand

s on the shoulders of the child in front of her. Tell the children to gently

rub and pat each other’s shoulder (you can massage the child at the end of the

queue). After a minute, ask them to turn around and massage the child who

massaged their shoulders before.

The back tickle

Tell the children to find partners. Then let them take

turns to gently stroke each other’s backs.

The body shake

Tell

the children jump up and down and wiggle their arms, legs and bodies to shake

out any physical tensions.

Relax your toes. Relax your nose.

Let

the children lie down and close their eyes. Guide them to relax different parts

of their bodies, starting with toes, working up slowly through the body. Say, “Wiggle

your toes. Let them relax.., wiggle your feet…, now let them relax.., move your

ankles from side to side.., then let them relax..’ and so on, ending with the

nose.

Helping children manage

their feelings

Here

are some other techniques you can use to help children learn to deal with their

feelings in a healthy and constructive ways:

- Teach feelings words

- Teach children to describe their feelings

- Don’t encourage “good feelings†or discourage “bad feelingsâ€

- Help children process their feelings

- Remind children that feelings don’t last forever

- Be a role model.

Teaching feeling words

Young children have limited language and communication

skills. They are still learning to use words to express their thoughts and

feelings. Even for adults, it can be difficult to find words to express strong

feelings. You can help children develop a “feeling vocabulary†by using words

that express feelings. Some examples are “happy, sad, ashamed, shy, angry or

hurtâ€.

Teach children to describe their feelings

Sometimes children cannot find the words to describe

their feelings. Their feelings may not fit neatly under the labels “happy†or “angryâ€.

You can help children to name their feelings, by asking them to describe exactly

what they are feeling inside their bodies. Young children can be very

descriptive. They may say things like, “I feel like I want to hide under a rock

where no one can see meâ€, or “If I can’t fit the pieces together this time, I

am going to explodeâ€.

Don’t encourage good feelings or discourage bad feelings

As adults we often label some feelings good feelings

and other feelings as bad feelings. Examples of good feelings are feeling

happy, or excited. Examples of bad feelings are feeling angry, or sad. However, it is not bad to feel angry

or sad. In fact, it is healthy to express your feelings, whatever they are. It’s

not okay to express our difficult feelings in ways that harm people or property.

This is true for children and adults. But if we express our feelings in healthy ways (through talking, drawing, stamping feet and so on), this is good for our mental health. So, as an ECD practitioner, you need to let children know that we all have difficult feelings sometimes. We need to express all our feelings, even the difficult ones. But we need to do so in ways that are healthy.

Help children process

their feelings

When you encourage young children to describe their feelings, you also

help them to express their feelings fully, and move beyond those feelings. It

takes practice and patience to work with children in this way, but it is the

best way to help children learn to manage their feelings successfully.

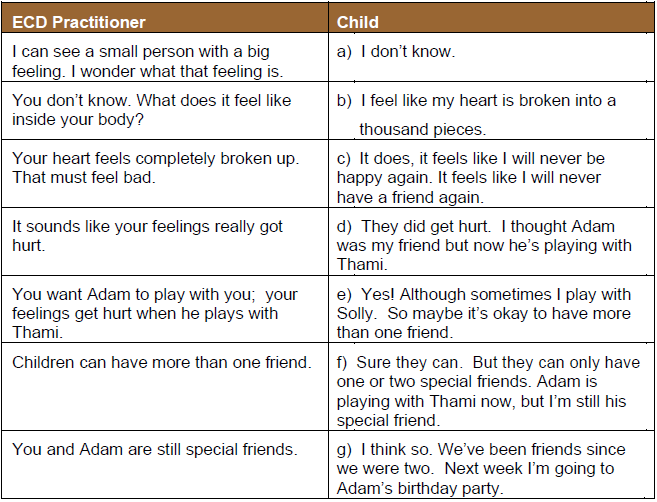

A conversation between an ECD practitioner and a child with a strong feeling:

Reading through this conversation, you will realise that the ECD practitioner is helping the child to describe and talk about his feelings and finding his own way of coping, to also come up with strategies and solutions.

Remind children that feelings don’t last forever

Children need to know

that feelings don’t last forever and that feelings do change.

They also need to know that often people will feel differently about the same thing and that it is okay.

Be a role model

How do you manage your own feelings? Think about it. Do you have

strategies that help you to express your difficult feelings in a healthy way?

This is important, because children will learn from you how to manage their

feelings. You are a role model for the children. Make sure that you stay in

touch with your feelings, and that you have healthy ways of coping with stress,

frustration, anger and irritation. This will help the children to learn and

apply these coping skills in their own lives.

4.7.3 Manage discussions

and/or conflicts sensitively

It is important to manage discussions and/or conflicts sensitively and

in a manner that supports the goal of group interaction or one-on-one

interaction, because there might be various group issues that should be worked

through and managed, e.g.:

- Disagreements in groups

- Personality clashes

- Conflict management

- Resolving deadlocks

- Positively summarising conclusions.

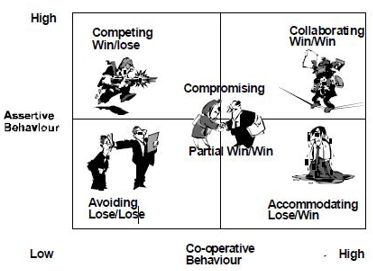

As with leadership styles, different writers present models of conflict management styles. There is not one best conflict handling style, but rather a best style for a given situation. We consider a few models and styles and indicate when each style is most appropriate:

Model 1. Here we can distinguish between five styles

1. The Problem Solver – refuses to deny or flee the conflict, presses for conversation and negotiation of the conflict until a satisfactory conclusion is reached. Most effective with groups that share common goals and whose conflict stems from miscommunication.

2. The Super Helper – they constantly work to help others and give little thought to self. This is the “Messiah†who is often passive in their own conflicts but always assists others to solve their conflicts. This style is to be avoided as one must deal with personal conflicts to be able to effectively help others.

3. The Power Broker – for this person, solutions are more important than relationships. Even if a person leaves the group, as long as a solution was achieved, they are satisfied. It can be used when substantive differences are so conflicting that mutually inclusive goals are not possible.

4. The Facilitator – they adapt to a variety of situations and styles in order to achieve a compromise between competing factions. It is effective for conflicts where differences are based on attitudes or emotions.

5. The Fearful Loser – this person runs from conflict probably because they are personally insecure. This tends to produce hostility and result in a weakening of leadership in the group.

Model 2. Speed Leas in “Discover Your Conflict Management Style†mentions six styles

1. Persuading – trying to change another’s point of view, way of thinking, feelings or ideas. Techniques used include: rational approaches; deductive and inductive arguments; and other verbal means. Persuade when there is great trust; when one party is admired; when goals are compatible; and when one party does not have strong opinions on the subject.

2. Compelling – the use of physical or emotional force, authority or pressure to oblige or constrain someone to act in a desired way. Use compelling infrequently; when you are threatened or under attack; when rights are being violated; when you have authority to demand compliance; when there is inadequate time to work through differences; and when all other means have failed.

3.

Avoiding – This is actually a category that combines four styles: avoidance (to evade or stay

away from conflict); ignoring (act as if the conflict is not going on); fleeing

(actively remove oneself from the arena in which conflict might take place);

and accommodation (going along with an opposition to keep the relationship).

Strategies include: procrastination (postponing unnecessarily); saying “yes†to

requests but then not acting on them; showing concern for the other without

responding to the problem; resigning; and studying the problem with no intention of

doing anything about it. Avoid this style when people are fragile or insecure;

when they need space to cool down; when there is conflict on many fronts

simultaneously; when differences are trivial (small); when parties are unable to

reconcile differences; and when the relationship is unimportant.

4. Collaborating – This is a process of co-labouring with others to resolve difficulties that are being experienced. It is also called joint or mutual problem solving. Collaborate when people are willing to play by collaboration rules; when there is ample time for discussion; when the issue lends itself to collaboration; where resources are limited and negotiation would be better; and when conflict and trust levels are not too high.

5. Negotiating – Also called bargaining, this involves collaborating with lower expectations. It is a process where both sides try to get as much as they can, realising there must be give and take. Where collaboration is a “win/win†strategy, negotiation is a “sorta-win/sorta-lose†strategy. Negotiate when there is something that can be divided or traded; when compelling (forcing) is not acceptable and collaboration has been tried and failed; when all parties are willing to negotiate; when the different parties have equal power; and when trust is high.

6. Supporting – Here one person will provide a support to the person who is experiencing conflict. It involves strengthening, encouraging or empowering one party so they can handle their difficulties. It involves support when the problem is the responsibility of someone else; when a party brings problems outside of your relationship with them; and when one party in the conflict is unwilling to deal with issues.

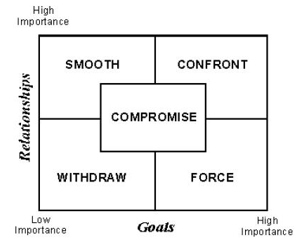

Model 3. Tension between relationships and goals

A third model focuses on the tension between relationships and goals in conflict

handling. When a leader becomes involved in a conflict there are two major

concerns to deal with:

(a1) Achieving personal goals and (b2) preserving the relationship.

The importance of goals and relationships affect how leaders act in a conflict situation. The following five styles of managing conflict are found:

1. Withdrawing – people with this style tend to withdraw in order to avoid conflicts. They give up their personal goals and relationships; stay away from the issues over which the conflict is taking place and from the people they are in conflict with; and believe it is hopeless to try to resolve conflicts. They believe it is easier to withdraw (physically and psychologically) from a conflict than to face it.

2. Forcing – people in this category try to overpower opponents by forcing them to accept their solution to the conflict. Their goals are highly important but the relationship is of minor importance. They seek to achieve their goals at all costs; are not concerned with the needs of other people and do not care if other people like or accept them. They assume that one person winning and the other losing settle conflicts. While winning gives them a sense of pride and achievement, losing gives them a sense of weakness, inadequacy, and failure. They try to win by attacking, overpowering, overwhelming, and intimidating other people.

3. Smoothing – for those who fall into this category, the relationship is of great importance, while their own goals are of little importance. They want to be accepted and liked by other people; they think that conflict should be avoided in favour of harmony and believe that conflicts cannot be discussed without damaging relationships. They are afraid that if the conflict continues, someone will get hurt and that would ruin the relationship. They give up their goals to preserve the relationship. They try to smooth over the conflict in fear of harming the relationship.

4. Compromising – people with this style are moderately concerned with their own goals and about their relationships with other people. They seek a compromise. They give up some of their goals and persuade the other person in a conflict to give up some of their goals. They seek a solution to conflicts where both sides gain something.

5. Confronting – people in this category highly value their own goals and relationships. They view conflicts as problems to be solved and seek a solution that achieves both their own goals and the goals of the other person in the conflict. They believe conflict improves relationships by reducing tension between people. By seeking solutions that satisfy both themselves and the other person they maintain the relationship. They are not satisfied until a solution is found that achieves their own goals and the other person’s goals and they want all tensions and negative

Supporting the goal of the group or one-on-one interaction

Within conflict management there is the danger that the group think may

be flawed and negotiating your way around changing this can be challenging. To

reach consensus (agreement) to support a more balanced or negotiated outcome it

is important to know what kind of group think could have a negative influence:

- The group overestimates its power

- The group becomes close-minded

- Group members experience pressure to conform.

Here are some principles for leaders to prevent group think and promote cohesiveness (interconnectedness):

- Establish a norm of critical evaluation

- Leaders should not state their preferences at the beginning of the group’s decision-making process

- Make sure that the group does not get insulated.

Cohesiveness come about when people are supporting group goals and within a one-on-one interaction.

Here is a list of four things that can be done or worked on within a more established group to make to create better cohesiveness:

1. Heighten the awareness of the values of membership. Stress the positive features of the group by speaking of the benefits the group offers. Therefore they will see the group as more attractive to them.

2. The group needs to appeal to satisfy everyone needs. One on One interaction to bring this home would be advised. Remember fulfilling individuals needs is a big factor that contributes to the level of cohesiveness in a group.

3. Enhancing of the group’s status will also help increase a sense of cohesiveness. This helps to make each member feel they have a higher status by being in the group. Therefore each member knows they have an esteemed place within the group.

4. An increase in group interactions helps to increase togetherness.

4.7.4 Put forward own position when confronted by opposing views

Parties

should be asked to describe recent disagreements. What were the issues, who

were involved and how was the conflict handled? What are the differences

between conflicts that were handled effectively and those that were not? Can

you see the different conflict styles evolving? If the parties can provide

answers to questions like these they will be ready to work on clarifying goals,

reconciling differences, and finding ways to resolve conflicts.

Clarify goals

Even

when people are in conflict they usually share many of the same goals in spite

of their differences. Both sides usually want to see the conflict resolved in a

way that will be mutually agreeable, beneficial to both, and inclined to

enhance the relationship so that future communication will improve. The youth

leader should try to discourage bargaining over positions and work from the

basis of the common goals that people are striving for. People should first be

reminded of the goals that they share, and then they should discuss their

differences.

Reconcile differences

The guidelines for

reconciling differences are:

Step 1: Take the initiative and go to the person who has wronged you

This

should be done in person and in private. In making this move, it is best if the

person goes with a spirit of humility, with a willingness to listen, with a

determination to be non-defensive and to forgive.

Step 2: Take witnesses along

If

the person will not listen or change, a return visit with one or two witnesses

becomes necessary. These people are to listen, evaluate, determine facts and

try to arbitrate (settle) and bring a resolution to the dispute.

Resolve conflicts

When

individuals or groups are in conflict, they have four main choices about the

direction they will take. They may avoid conflict, maintain, escalate, or

reduce it.

Sometimes people do not want conflict resolution and may decide to go in different directions.

Conflict resolution means that the youth (ECD centre) leader will be involved in negotiation and mediation. It is not always wise for leaders to get involved in someone else’s conflict even when they are asked to do so, as they will feel pressurised to take sides; be required to make quick analytical decisions; and be responsible for keeping communication open.

When youth leaders do choose to get involved they should try to show respect for both parties; understand both positions without taking sides; reassure people and give them hope; encourage open communication and mutual listening; focus on things that can be changed; try to keep the conflict from escalating; summarise the situation and positions frequently; and help the parties find additional help if the mediation is not effective.

We propose that you use the following four-step method in conflict resolution:

Step 1: Separate the people from the problem

This

means treating one another with respect, avoiding defensive statements, or

character judgments, and giving attention instead to the issues. Each side

should be encouraged and helped to understand the other’s fears, perceptions,

insecurities and desires. Parties should think of themselves as partners in a

side-by-side search for a fair agreement, which is advantageous to each side.

Step 2: Focus on the issues, not the positions

When people identify the real issues and stop trying

to defend rigid (inflexible) positions they are on their way to resolve their

conflict.

Step 3: Think of various options that might solve the problem

In

the beginning there is no attempt to evaluate the options or to arrive at a

single solution. Each side makes suggestions for options in a brainstorming

session. After a number of creative and perhaps new alternatives have been

proposed, each option can be evaluated.

Step 4: Insist on objective criteria

Conflict

is less likely to occur if both sides agree beforehand on an objective way to

reach a solution. If both sides agree to abide by the results of a coin toss, a

judge’s ruling, or an appraiser’s evaluation, the end results may not be

equally satisfying to both parties but everybody agrees on the solution because

it was determined by objective, fair and mutually accepted methods.

4.7.5 Use and adapt approach or style appropriate to interaction context

The

most important information that is exchanged during conflicts and arguments is

often communicated nonverbally. The style that you communicate in is important.

Nonverbal communication includes eye contact, facial expression, and tone of

voice, posture, touch, and gestures.

When you are in a conflict situation, you must pay close attention to the other person’s nonverbal cues; this will give you clues on what the other person is really saying, respond in a way that builds trust, and get to the root of the problem. Simple nonverbal signals such as a calm tone of voice, a reassuring touch, or a concerned facial expression can go a long way toward defusing a heated exchange.

Your listening skills will be tested too, as language that has conflict undertones must be managed. When aggressive language is used, it is pointless to become engaged with the poor behaviour. Here are some tips to manage this.

Do the following:

- Keep your voice calm and even

- Keep your facial expression as neutral as possible to avoid showing emotion

- Ensure eye contact to show you are paying attention

- Make sure the person has enough physical space

- Take a few seconds to calm yourself down before interacting.