Unit 5 Online Study Unit

Learning Unit 5: Reflect on own facilitation and use of resources

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to reflect on own facilitation and the use and effectiveness of the resources. You will be able to:

- Reflect on your own facilitation

- Evaluate spoken discourse

- Reflect on the use and effectiveness of the resources.

Reflect on own

facilitation and use of resources

Reflecting on your practice is a way of evaluating

your effectiveness. It is also a way of finding opportunities to improve your

facilitation skills. New children who enter the playground, new insights you

develop from your own experience and a willingness to try new things, all contribute

to good facilitation. The objective of your facilitation is to meet the

development aims of the group of children you are working with.

5.1 Reflect on own facilitation

You will need a reflection journal to help you reflect

on your own facilitation. You will also use your reflection journal for the

tasks in this study unit. Hopefully, you wil continue to use your journal

during the rest of this course, and after you have completed it. Let’s begin

with an activity in which you make your own reflection journal.

5.1.1 Reflect on own facilitation approach in relation to the

developmental aims

We reflect on our own

practice for many reasons:

- To learn from our mistakes

- To identify our area of strengths and our areas of challenge

- To make sure that we facilitate activities effectively

- To check the developmental appropriateness of our activities

- To ensure that our activities match children’s interest

- To identify ways in which we can change and grow

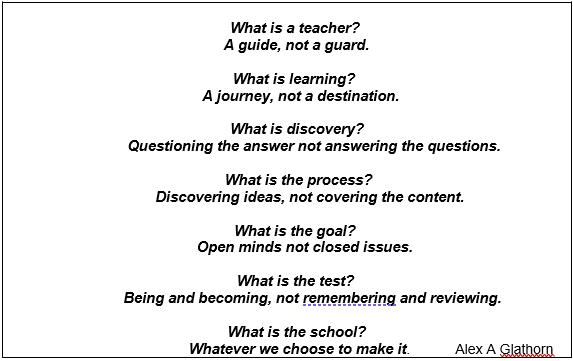

Let’s explore this question by reading a poem called “What is a teacher?†This poem will help you to think more deeply about your role as an ECD practitioner.

This description of a teacher helps to inspire us, and helps us to realise that we are constantly learning, growing, discovering and changing. When we feel truly alive and creative as ECD practitioners, our minds and our ears are open. We can use our skills, experience and training to provide a creative, well-structured, educationally rich environment. Within this environment we can allow ourselves to learn, explore, change and grow together with the learners in our care.

As a nation we grow and change in our families, our school, and our culture. We learn to choose a career and stick to it; we learn to become competent at our chosen job, through studying. We learn to keep our work and our lives neatly controlled.

These words that you read from the poem covering the content, closed issues, remembering and reviewing, guarding, destination, answering the question, these words describe the ethos of our studies. Ethos means the sense of beliefs we have, about our social behaviour and relationships. To some of us it describes the ethos we that carry into our work as ECD practitioners.

Let’s reflect on the inspiring words we read from the poem: guide, journey, questioning, the answers, open minds, being and becoming. These words are alive with explanation and adventure; they allow and encourage growth and change.

Reflecting on your own practice means to look carefully and critically at your work as an ECD practitioner in your classroom.

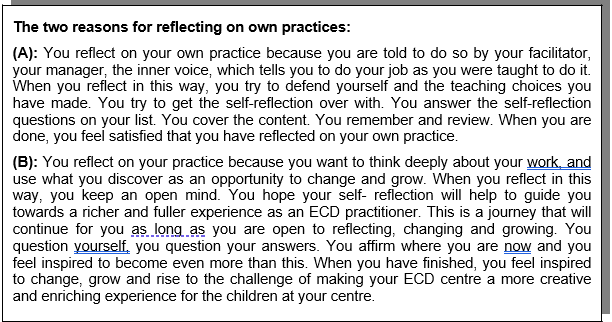

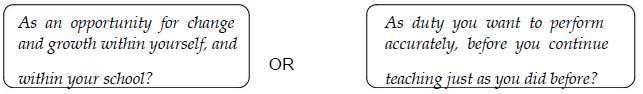

As an ECD practitioner, you will reflect on your own practice. It is part of your job to do so. The question is, how will you reflect on your practice?

Only you can answer these questions. Think about it. Your attitude to self-reflection is what is important here. Which choice will you make?

Often, the nature of ourselves that we present to the outside world is different from the way we truly think and feel about ourselves. For example, we may be confident and assertive at home, within the safety of our family; but outside the home we are shy, unsure and self-evaluating. Sometimes, we believe that others see us in a more negative light than they actually do.

When our outer and inner selves are different from one another, it does not mean we are being dishonest or untrue. Usually, we contain all of these qualities – both the inner and the outer ones. However, when we split our personality in this way, it can be hard to be who we truly are. It can be hard to draw on our inner qualities in the outer world.

That’s why it helps us to try to be congruent (harmonious). That means to claim ownership of all our qualities, so that we have the freedom to be who we are.

5.1.2. Obtain feedback from a variety of relevant sources

The

value of your facilitation can be demonstrated by the happiness, positive

adjustment, growth and holistic development of the children in your playgroup.

But this is generally only clear after a year or so in which to measure these

changes. A more useful and immediate way of getting a sense of your

effectiveness is to ask colleagues and parents for feedback.

Feedback from colleagues

In

your ECD environment, there are colleagues who may overhear you with the

children or see your group outdoors. They may give you informal feedback or

comments which may upset you. To get more comprehensive, accurate and useful

picture of how you are managing your facilitation, you could use the following

criteria and strategies (remembering always to keep a running commentary in

your reflection journal to support your thinking and your efforts to improve).

Criteria for observation

Bear in mind that every facilitator has a personal style. The two main criteria for anyone to evaluate the facilitator should be:

- The clear communication with the children which supports them to engage with the activity productively (attending the promoting)

- The warmth, attention, support and good behaviour management the facilitator shows the children (the quality of the relationship).

Share an activity

Invite a colleague to share a structured activity with

the group (like an obstacle course, including balancing and skipping) and

schedule it to take place while her group is having free outdoor play. Ask her

to get another staff member to watch her children while she joins you to

observe your facilitation. Again, identify for her any specific points of

facilitation, or an input, that you may be finding difficult.

Your colleague should make accurate observation and reflection notes and the two of you should have a structured meeting with your supervisor present, to discuss the feedback.

Regular observation

This

process of observing and giving feedback to colleagues should happen regularly

for all facilitators so that they can share expertise and improve the quality

of facilitation.

Support group

Have

a fortnightly staff support group in which you and your colleagues share your

collection of notes about any activity that has been a problem or has presented

difficulties. Together, discuss and brainstorm solutions. Then put those

suggestions into practice and feedback your results to the group at the next

session. You should keep reflection notes in your journal about the group at

the next session and about this process and which kinds of feedback are

helpful.

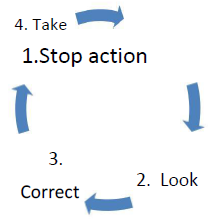

Stop look, correct, take action

Use

your reflection journal to take some private time to think about solutions, or

corrective actions that you could try. All the feedback you receive needs time

to settle and you may be able to identify a common theme or single behaviour

that may be the effective solution to different problems. After this reflection

and after deciding which actions to take, specify those actions in your

reflection journal. Then follow through on the feedback with an action stage in

which you try out suggested changes to your facilitation (if any). It is

essential to keep building your skills and experiences through this constant

feedback and correction process.

Feedback from parents

There

are many informal opportunities for feedback from parents, who often enjoy

sharing stories their children have told them about activities in the

playgroup. Bear in mind that the children’s report from a parent about a child

having some negative experience in any activity may quite possibly be a

reflection of the child(ren)’s perspective.

Orientation of parents

Before

your year begins, send an introductory letter to parents explaining your

facilitation style and philosophy very briefly. Give a concrete example of how

your style works (for example, “I attend to each child’s individual learning

needs and encourage participation to the best of the child’s ability. There is

no pressure to create any specific product or to compare work with other

children. The focus is on the individual child’s development.â€) This helps

parents to recognise that your approach is child-centred and not parent-centred

(because some parents are product-focused rather than process-focused regarding

what their children are learning). In the same letter invite feedback from

parents via the telephone in the afternoons, or via the suggestion box, or by

attending the feedback session in the regular parent meetings.

Parent meetings

To

provide better feedback opportunities for you, try to set aside 15 minutes of

any parent meeting for feedback from parents to you. When you notify the

parents about any meeting, list this feedback time on the agenda for the

meeting so that parents can come prepared to talk about any issues that concern

them. This may or may not include feedback on your facilitation, but your

facilitation will benefit from being informed by what is of concern to parents.

Suggestion box

You could draw up a feedback or suggestion slip for

parents to fill in at any time and have a locked box at the front door of the

playgroup where they could leave these slips.

Dealing with parents’ feedback

It is unusual for a parent to give feedback

specifically about the facilitator’s approach and style of facilitation. However,

it remains important to give them the opportunity to give you feed- back and

for you to listen respectfully to whatever they may say. Your decision as to

how to use the information depends on the nature of the information. Use these

general guidelines in responding to parents:

- Keep an open mind

- Keep communication lines open

- Keep the child’s interests your top priority

- Be willing to do what you can to make it easier for the child and her parents to accept the playgroup and you as the facilitator

- Keep record of any feedback from parents

- Use your reflection journal to help you arrive at conclusions or strategies.

Feedback from other

sources

Stay

informed on early childhood education by reading and continuing to discuss your

work with other playgroup facilitators in your community. Remember to keep the children’s

details confidential.

5.1.3. Reflect on

strengths and weaknesses of the way in which development is facilitated

Since

it is so important to be open to feedback, you should try to analyse the

feedback calmly and make sure it can be useful to you. If you like, ask the

person giving open feedback to help you by using the tools you will explore in

this lesson.

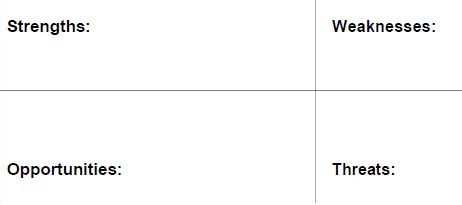

Here are three devices or tools you can use to analyse the strengths and weaknesses of your facilitation:

- SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats)

- Mind maps

- Drilling down information.

SWOT analysis

SWOT is related to a person or organisation in a

particular situation. You can use the information that you obtain from this

analysis to decide what changes you need to make in order to improve the

situation.

Try to think of new children admitted at your centre with Setswana as their first language, and were struggling to keep up with the rest of the children during story time which was presented in English.

Use the scenario to complete the table below using SWOT analysis to reflect on your facilitation skills in a multi lingual ECD context. Use the table below to conduct this self-reflective exercise.

A SWOT Grid

Mind maps:

A mind map is a visual tool that allows us to put thoughts on paper

quickly and simply, and indicate the relationships between them. If you are not

familiar with mind maps, you could visit your local library to read more about

it.

Drill down information:

It may be more difficult to find information about what has NOT worked

in your facilitation. In order to analyse what happened, try the “drill down

technique†of asking questions and getting to the smaller details of

information which may reveal the success of the problem.

5.1.4 Reflect on the

extent to which facilitation contributes meaningfully to the overall aims of

the ECD service

To make the best use of suggestions and

recommendations that were given as feedback on the facilitation, follow a

structured process of:

- Recording the feedback

- Reflecting on the changes needed

- Implementing the changes

- Making recommendations from the results.

The value of reflection

for the ECD service

Building

better facilitation practice is important to the Early Childhood Education service

in South Africa. It is your duty to maintain standards of practice and to

participate in generating new knowledge and expertise about facilitation. In

this way the fields of knowledge can grow and practitioners increase in

effectiveness, which will have a positive outcome for children’s development.

Commitment to a good quality ECD service, for the sake of children’s rights, means that you should work together with other ECD practitioners or organisations to maintain standards of facilitation. When you are working towards promoting a high quality ECD service, you need to ensure that the service you offer is the best. This can be achieved by constant reflection, evaluation and improvement on the quality of your facilitation.

Reflecting on your own practice may provide you with experience to which you can refer, but you should also reflect on the knowledge you gain from:

- Attending workshops

- Reading useful articles

- Listening to or watching relevant radio or TV programmes

- Learning from others

- Asking questions.

How to implement changes

It

takes courage to try something new. But the children are forgiving (as long as

you do no harm) so at the risk of making a mistake or making a fool of

yourself, feel free to try new strategies. Use your mass of experience, insight

and knowledge of the children and of your reflection, to record your conclusion

about what needs to be done and then simply do it.

The most important part of this process is the assessment that you make after implementing the change, to evaluate the effectiveness of your new strategy. Share your results with your colleagues so that others may also try to apply the new strategy, and everyone may benefit. The strategy may be further modified: the feedback loop shown in the diagram below can be repeated again and again, in a sequence “Stop, Look and Correct, Take Actionâ€.

Sample of the feedback loop for implementing changes

How to build better facilitation

While you should reflect on the strategies suggested to deal with

feedback from parents, we should also

check whether those strategies worked and make recommendations about them:

- Keep an open mind

- Keep communication lines open

- Keep the child’s interests on your top priority

- Be willing to do what you can to make it easier for the child and her parents to accept the playgroup and you as the facilitator

- Keep observational records about any feedback

- Use your reflection journal to help you arrive at conclusions or strategies

- Implement the strategies or solutions

- Check their effectiveness

- Make recommendations to build on strengths.

5.1.5 Provide recommendations

to build on strengths and address identified weaknesses

Having your facilitation evaluated by an observer provides enough of a

stimulus for change. So hopefully you will be able to let go of any problematic

techniques, behaviours or attitudes which you discovered in your practice.

When you are writing formal documents, it can be hard to express yourself naturally. To make recommendations about the necessary changes to facilitation, simply write them the way you would say them to a friend or colleague. Then make sure that they are in clear and simple language. Would a friend understand them if she knew nothing about ECD? That’s how clear they should be. Work with friends to get them logical and clear enough for her to understand. Use short sentences for each point.

As an example, you might want to recommend that a colleague changed her habit of clapping her hands loudly at the start and end of every activity because it frightens the quieter children and disturbs the other staff. You find it slightly aggressive and disturbing.

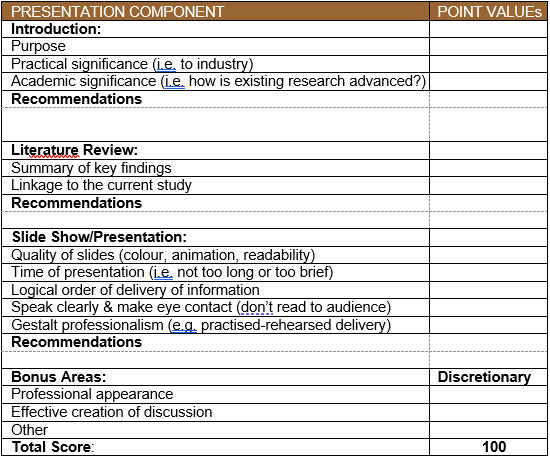

5.1.6. Record findings and recommendations to support future facilitation

It is always good to have clear guidelines when listening to and evaluating a presentation. Simply giving verbal feedback is not sufficient and it is considered correct practice to record the recommendations on a sheet, as in the example below:

5.2 Evaluate spoken discourse

In

writing and speaking we can use different types of language. In discussions at

work, with clients, strangers, and other people we follow certain unwritten

rules. Using these unwritten rules are called “register useâ€. Register use can

help you to communicate effectively. Incorrect register use can cause problems

at work, cause people to ignore you, or, at best, send the wrong message. Of

course, correct register use is very difficult for many learners of English.

This feature focuses on different situations and the correct register used in

the various situations. To begin with, let us look at some example

conversations.

Formal

In the business environment it is customary to address

your client in a formal register. If you see your client more frequently, the

degree of your formality may decrease.

Informal

You use this type of language with people who are

familiar to you. You may make good use of this register in verbal

communications with clients, but you should first find out whether or not your

client would be offended by your use of this register.

Slang

Slang is used by a specific group of people who understand the meaning

of the words that are used. Different geographic communities may use words that

are only understood in that community. For example, a group of friends may have

made up their own words and “group language†which outsiders will not be able

to understand.

In an organisation, slang is company-specific jargon that is NOT formally accepted. Slang may be appropriate to use in interacting with your colleagues, but is not acceptable for use with clients.

Jargon

Jargon

is subject-specific or technical language that is used by a specific group of

people, which is normally not clear to others who are not part of this group.

Jargon is useful when speaking to experts and members of the groups as it

avoids long-winded explanations. But when dealing with a non-layperson, avoid

jargon and use language that explains the concept to them clearly.

Verbal mannerisms

Verbal mannerisms are the phrases we use subconsciously such as “uhmâ€, “wellâ€,

“you knowâ€, “erâ€. Sometimes we use these to “buy time, when we are thinking

about an appropriate answer, “uhm†or to lead into a subject – “well…â€.

Sometimes we use them if we are nervous. Beware that they can interfere with

meaning, give away a lot about your emotional state and be distracting for your

listener.

Plain language

Do

not use convoluted words. See! “Convoluted†is a word that shows off my

vocabulary but could cause misunderstanding. To ensure that readers or

listeners undxerstand your language the first time round use plain language

that is simple to understand.So - Do not use words that are difficult or

complex when a plain word will do. This is not to say that you should not build

your own vocabulary, to ensure that you understand people who do not use plain

language.

5.2.1 Identify points of

view and describe the meaning in relation to context and purpose of the

interaction

We will

discuss evaluation in the next few sections. The author of the text could be

considered to be the narrator (story teller) and you are the observer.

There are five possible viewpoints from which a text can be narrated:

First-Person: The narrator tells “I†or “my†story. Also, this may be “we†or “our†story. e.g.: We went to the dam.

Second-Person: The narrator tells “you†or “your†story, usually used for instructions. e.g.: The first thing you need to do is jump.

Third-Person Objective: The narrator tells “his†or “her†story and does not reveal any character’s thoughts or feelings. Characters may reveal their feelings through actions or dialogue. e.g.: She walked into the gym. A man walked past and said, “Hey, you are looking mighty fine.â€

Third-Person Limited: The narrator tells their story and reveals one character’s thoughts or feelings. e.g.: She was overjoyed at the fact that Sally liked her and she wasn’t paying attention as she walked down the street. A man drove by and yelled, “Hey, watch where you’re going!â€

Third-Person Omniscient: The narrator tells “his†or “her†story and reveals more than one character’s thoughts or feelings. e.g.: Jenny was overjoyed at the fact that Sally liked her and she wasn’t paying attention as she walked down the street. Jenny was having a good day, and as he was driving by her, Tom tried to startle her: “Hey, watch where you’re going!†Tom yelled in a fun way.

Modes of narration (storytelling)

As we

saw above, there are six key terms used in the study of narrative view point:

first-person, second-person, third-person, third-person objective, third-person

limited, and third-person omniscient. Each term refers to a specific mode of

narration (method of storytelling) that is defined by two things: the distance

of the narrator from the story and how much the narrator reveals about the

thoughts and feelings of the characters (narrative access). Let’s take a closer

look at each term.

First-person narration

In

this mode, the narrator is usually the central character in the story. But even

if this character is not the protagonist, they are directly involved in the

events of the story and are telling the tale “first hand.†First-person

narration is easy to identify, because the narrator will be telling the story

from the “I†perspective. Readers should watch for the narrator’s use of first-person

pronouns- “I, me, my, our, us, we, myself, and ourselves,†as these will

usually indicate that the passage is narrated from the first-person

perspective. Remember, with this skill readers are trying to identify the

perspective of the narrator; therefore, one must ignore the dialogue of

characters (indicated by “quotation marksâ€) and solely focus on

narration, otherwise one is not analysing the narrator’s point of view.

Second-Person Narration

In

this mode narration “you†are the star, such as in this example: you jumped up

and down. As it is generally awkward for a story to be narrated from “yourâ€

perspective, this mode of narration is not used very often in narratives and

stories. There are some exceptions, however, and second-person perspective is

the primary mode of narration for your own adventure books and similarly styled

writings. More frequently, directions and instructions and usually narrated

from second-person perspective. In most cases, directions will be written in

short imperative sentences, where the implied subject is “youâ€. But even when “youâ€

is not clearly stated, it is understood that “you†are the subject of

directions and instructions.

Third-Person Narration

With

this mode of narration, the narrator tells the story of another person or group

of people. They may be far removed from or not involved in the story, or they

may be a supporting character supplying narration for a hero. Frequent use of “he,

she, them, they, him, her, his, her, and their†by the narrator may indicate

that a passage is narrated from third-person perspective. There are three

distinct modes of third-person narration: objective, limited, and omniscient.

Which mode the narrator is using is determined by a single variable - how much

the narrator accesses the thoughts, feelings, and internal workings of the

characters and shares them with the reader through narration. Characters’

feelings and motivations can be inferred and understood through their behaviour

and dialogue in each of the three modes of third-person narration. However, when

readers want to determine in which mode the narrator is operating, they should try

to find instances where the narrator explicitly reveals a character’s thoughts

or feelings.

Third-Person Objective Narration

In

this mode of narration, the narrator tells a third-person’s story (he, she,

him, her), but the narrator only describes characters’ behaviour and dialogue.

The narrator does not reveal any character’s thoughts or feelings. Again,

readers will be able to understand characters’ thoughts and motivations based

on characters’ actions and dialogue, which are narrated; however, the narrator

will not explicitly reveal character’s thoughts and/or motivations in

narration.

Third-Person Limited:

When a narrator uses third-person limited perspective,

the narrator’s perspective is limited to the internal workings of one

character. In other words, the narrator reveals the thoughts and feelings of one character through explicit narration.

As with objective narration, readers may be able to infer characters’ thoughts

and feelings based on the behaviours and dialogue of those characters, which

are narrated, but the narrator also directly reveals the central character’s

internal perspective.

Third-Person Omniscient:

In this mode of narration, the narrator allows readers the most access

to characters ‘emotional state and thoughts. With third-person omniscient

narration, the narration will reveal more than one characters’internal

workings. The base word omni means “all,†and scient means “knowing,†so

omniscient roughly translates to “all knowingâ€. So in omniscient narration, the narrator is all knowing.

5.2.2 Identify values,

attitudes and assumptions in discourse and describe their influence on the

interaction

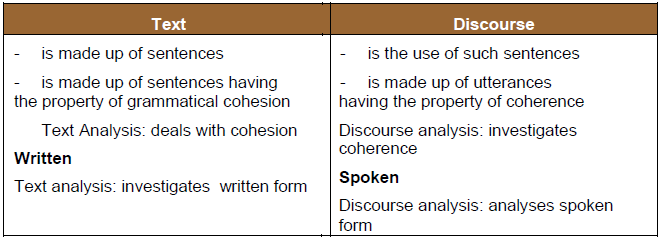

Discourse is a particular phenomenon; it is NOT the same as text

analysis. Below is a table showing the difference.

Discourse is generally “spoken†text; it is therefore longer than only one sentence. To find values, attitudes and assumptions in discourse and to understand the “conversation†you have to consider the following questions:

- Are there hidden relations of power in the text?

- Who is exercising this power? (i.e. who presents it)

- Who is the audience?

- What is left unsaid?

- Is the passive voice used?

- To what extent is descriptive language used for emphasis?

5.2.3 Identify and

interpret techniques used by speaker to evade or dissipate responsibility for

an issue

In

this type of analysis, it is as if you are listening to a conversation. Therefore

you have to be aware of the various ways the speaker could use in order to try

to avoid responsibility.

- What is the tone of the speaker?

- Is there an element of power play?

- The discourse will have elements such as issues of identity, dominance and resistance

- Does the language contain obvious or subtle words that may stigmatise the vulnerable, exclude the marginal, or dominate?

In speaking or writing there will always be evidence of the world view, and you need to identify taking perspectives on what is “normal†and what is not; what is “acceptable†and what is not; what is “right†and what is not.

5.2.4 Describe, explain and judge the impact of spoken discourse

The

impact of spoken discourse is just as powerful as that of the spoken language.

How you listen in your own language and use it varies in different social

situations – for example, how your language changes when speaking to different

people (such as your friends as opposed to your parents) Speech can also give

you the sense of belonging to a group – for example a regional group, an age

group, an interest group, or an ethnic group (note that this unit is not just

about spoken English, it is about spoken language in general).

Studying the spoken language also includes looking at the way culture and identity is reflected in the way we use language. It also considers how our language changes with society and new technologies.

The impact of spoken languages varies according to its intent, which may be to:

- Explain

- Persuade

- Defend

- Recount

- Encourage

- Instruct

- Entertain.

The way that spoken language is delivered also determines the impact. There are many different ways, for example:

- Spontaneous

- Scripted

- Formal

- Informal

- Conversation

- Debate

- Presentation.

You could think of written language as static or unchanging, whereas spoken language is dynamic.

5.2.5 Analyse own responses to spoken texts

The

act of reading is like a dialogue between the reader and the text, which has

meaning only when the two are joined in conversation. Therefore the text now

gains a “life†as it can only exist when it is read by and interacts with the

mind of the reader.

Thus you are no longer a passive recipient of what the text says, but rather have taken an active response. What occurs then is that your own inner world become linked to the text. In that way you begin to fill in the spaces left by the text. So this means that every reader will attribute a different meaning to the text, an inner dialogue that differs from person to person.

This form of analysis as deep as what the words and phrases in the text play when interacting with the reader. Furthermore, the sounds and shapes that words make or even how they are pronounced or spoken by the reader can fundamentally change the connotation (association) of the text. As the reader goes deeper into the topic, it will also create a different response to text. For example, a spoken discourse on violence towards woman will have a different response from a perpetrator, a victim or even a lawyer. Culture too plays a role in response.

Taking all of this into account, the context of the spoken text and the response may not always match its purpose. Therefore the reader should remember that, instead of emotionally responding, it may take a while before a more appropriate, less biased response arise present.

5.3 Reflect on the use and effectiveness of the resources

Now

we return to using resources. Once you have made or adapted and used a

resource, you need to reflect on how effective it was in achieving its purpose

and whether any improvements or changes are needed. The act of reflection

implies that you are willing to make changes whenever necessary. Your resources

are not adjustment only once, since a variety of children will pass through

your hands. Therefore this (resource adaption and use is not a static,

once-off, and it requires an ongoing reflective attitude.

Why reflect?

Reflection

is about examining and reviewing a product or process. It is defined as: “to think,

ponder, or meditate’. We need to reflect on our resources in order to do

the following:

- Ensure that the resource supported the activity adequately and did not distract from the planned learning outcomes

- Identify whether it was useful, effective and appropriate for the activity and the developmental needs and interests of the children

- Identify its suitability in terms of an ECD context and learning programme

- Look at possible improvements as regards its safety, durability, bias and ability to meet any special needs of learners.

We do not always willingly reflect on our work – we normally only do so when it is required of us and somehow feel that we are on the defensive. Unless we are honest in our reflections, we will never be able to improve on our efforts or the resources we have provided. There is a difference between being overly critical and reflective. When we reflect we do so because we want to grow and learn.

As an ECD practitioner, you will need to develop these skills and reflect on your practice so that you can develop yourself and your facilitation skills. You have to challenge yourself to become more creative and to grow. As you grow, so the children in your care will benefit and you will find that dealing with the challenges of each day in a school become easier.

Instead of seeing reflections and evaluations as a burden, you should rather see them as an opportunity.

Remember, “Attitude determines altitudeâ€.

5.3.1 Reflect on the

extent to which the resources support the purpose of the activities

We

have discussed the theory of reflection. Now we need to put this into practice

and apply it to the resources that you have adapted or made. Let’s look at the

questions you should reflect on in a little more detail.

Does the resource

support the purpose of the activity?

What was the purpose

with the resource? Why did you make it or use it?

This refers back to the developmental outcomes we looked at earlier in this programme – namely, physical, cognitive, language, social, emotional, creative and moral development.

For example, you have drawn a hopscotch game outside

and provided the children with colourful plastic counters to mark their places.

Your intention was to facilitate two areas, namely gross motor development

(hopping and jumping) and social development (taking turns). You would then

reflect that it had supported both areas as Mary, Alicia and Thembi had played

there.

For example, you have drawn a hopscotch game outside

and provided the children with colourful plastic counters to mark their places.

Your intention was to facilitate two areas, namely gross motor development

(hopping and jumping) and social development (taking turns). You would then

reflect that it had supported both areas as Mary, Alicia and Thembi had played

there.

5.3.2 Reflect on the usefulness, effectiveness and appropriateness of

the resources

The

resource will need to meet the interests of the children, be developmentally

appropriate, suited for any special needs, bias-free, safe and durable.

Let’s go back to the hopscotch:

- Only three children played with it so it may not meet the interests of the twenty-seven other children in your group.

- It is developmentally appropriate as you are teaching the five-year-olds who are able to hop on one foot and enjoy group activities

- Mandla could not play as he is in a wheelchair but he could have been encouraged to throw the counter for another child. (It must be noted that not all children can always be accommodated in every activity but we strive to include them as far as possible. As long as there are activities that they can do or a level of involvement that they can achieve, it is acceptable.)

- There was no cultural or gender bias even though only the girls wanted to play

- The game was safe as it was played on a flat part of the paved area, away from the wheel toys

- Durability is not really an issue as it can easily be redrawn with chubby chalks as needed.

5.3.3 Reflect on the

usefulness of the resources and suitability of the environment

Not

all resources will be suitable to be used by all ages as babies, toddlers and

young children have varying developmental needs. Some resources, though, may be

used by different ages and stages, for instance generic (general, non-specific)

toys like dolls or balls or equipment like shelves, furniture for the house

corner and mirrors. The more uses a resource has, the more valuable it is.

When setting up an ECD centre, including the various playrooms and outdoor areas, you will need to bear in mind that they should form a cohesive whole and that the children will normally move up class by class until they leave to go to formal schooling. The learning environment that you create should:

- Support the philosophy and ethos of ECD – most importantly that children learn through play

- Allow for sensory and motor exploration as this is the predominant mode of learning at this age

- Be developmentally sound for the children

- Incorporate both the familiar and unfamiliar

- Be free from cultural, gender and racial bias

- Be flexible and adaptable so that changes can be made to accommodate special needs of children and special events or circumstances

- Be healthy and safe for the children as well as the adults

Remember that your class may only be a part of the whole and that you also need to take responsibility for common areas such as passages, entrance halls, etc.

5.3.4 Identify and note

ways to improve upon the selections and adaptation for future resourcing

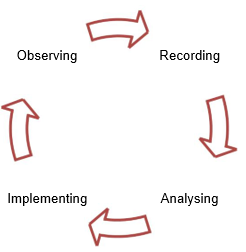

There

are four basic stages in reflection, which are cyclical in nature (it follows

on eacgh other in a cycle): you observe, record your observations, analyse your

observations, and implement them. You then start again: observe the changes,

record these observations, analyse whether the changes have worked, implement

further changes if need be…..and so it continues. Each time your practice

improves.

The cycle of reflection:

You cannot observe something unless you look at it very closely. Observations are also not haphazard (random) but planned and structured to be as effective as possible. While you may not realise it, you are observing children all the time while working with them. You notice when they are not feeling well or their behaviour is unusual; you get to know their likes and dislikes in terms of food, activities and friends. This coincidental, unintentional observation is valuable to get to know the children you are dealing with and to plan appropriate activities for them.

There are two kinds of observation:

1. Incidental observation: occurs when you are busy with children and note “by the way†what they are doing, what skills are weaker or stronger, what activities the child likes or dislikes, how they are behaving, who they are interacting with, etc.

2. Focused observations: are more formal and directed towards a specific skill or behaviour. Combined with the observations are recordings – in notebooks, journals, on tape, on camera, with a checklist or a rating scale. These are the observations that you will use to reflect on your resources.

Observations can only be effective if the following conditions are met:

- Time is set aside and the content of the observations and methods are planned in advance. You cannot multi-task and must use focused time where you will not constantly be interrupted

- You observe more than once. You will not get a true reflection if you observe during only one session

- They are comprehensive and include details

- You contextualise the behaviour and reactions of the children in terms of their age, needs, environment, stage of development, etc

- You do not jump to conclusions or allow your perceptions to impede on the process

- Children do not feel that they are being judged or uncomfortable in your presence.

Recording

There

are several ways to record these observations. Recording is vitally important

as we cannot remember all that we observe and if we rely on our memory, we may

forget important points. We will also not have a factual reflection of events

or reactions. Recording may take the form of anecdotal notes, rating scales,

checklists and journals.

Anecdotal notes

These

are useful when observing children’s behaviours or particular children. You can

use a notebook and allocate a page per child and you could record observations

over a period, by noting as a heading each time, the date, time and activity

being observed. The observations can be:

- Factual – based on yes/no answers

- Descriptive – you use your own words to describe what you see, more subjective in nature as you are interpreting actions that you see

- Quotes – use quotation marks to indicate what a child has said. The words must be transcribed verbatim (word for word).

You could use this method for recording the use of your resources. You could observe children playing with a resource that you have made or adapted and observe their reactions, record what they say and describe how they use the item.

Rating scales

The

rating scale is normally 1–10 or 1–5. You would again need to prepare this

ahead of time and determine the questions you want answers to. This may be a

good way of determining how popular the resource is or how safe and durable.

The rating scale should also have space for you to write an explanation for the

ratings so that you will know what changes to make to improve the scores.

Checklists

This helps you to focus your attention on important

aspects that need to be observed. This would be very useful when looking at

skills such as cutting. You could have columns with questions such as the

following:

- Does the child hold the scissors correctly?

- Can the child cut straight lines?

- Can the child cut around shapes?

Checklists must be developed before you start observing. if they are assessing a skill, they should be based on developmental expectations.

Checklists may be very useful to determine whether the resource you have used is developmentally appropriate, suits the interests of the children and is free from gender, cultural or racial bias.

Journals

You

should be familiar with this method as you are sometimes asked in your study

guides to reflect on issues in journals. Journals are very personal and give

you the opportunity to reflect honestly about your feelings, thoughts and

experiences.

They can also be used for you to record how you felt about the resource, what your expectations were and how you felt once they had been used. It is also a good place to note possible improvements or adaptations that may be needed.

Analysing

Observations and records have little value if they are

not used. Analysis involves breaking the whole into smaller parts so that you

can understand them more clearly. You will need to use your recordings on your

resources to help you understand:

- What worked or didn’t?

- Why children reacted in the way that they did?

- In what ways you can improve on the resource?

Hint: the more comprehensive your recordings, the easier you will find the analysis.

While this sounds very easy, you will need to use your knowledge of developmental norms and child behaviour to assess whether it was effective and supported the activity, the needs of the children and their interests.

Implementing

Implementing means putting something into practice (such

as recommendations). Once you have analysed your observations and decided on

changes that are needed, you should make these changes.

For example, you may have made a book for the children. You noted that the children enjoyed looking at the photos of themselves, but that some pictures became worn and started tearing because the children handled the book so much. You will then reprint those pictures if possible and cover them with laminating plastic so that they can better withstand the wear and tear.

Sometimes we do not implement the changes immediately as the resource is not worth saving or has served its purpose. We will note, though, for future reference, what should be done and we can go back to our analyses to look at our suggestions.