Unit 6 Online Study Guide

Learning Unit 6: Observe and report on child development

After completing this learning unit, you will be able to observe and report on child development. You will be able to:

- Observe babies, toddlers and young children

- Record observations

- Give feedback on observations

- Use strategies to be an effective speaker in sustained oral interactions.

Observe and report on

child development

What is observation and

why is it important, you ask?

- Observation takes place in an environment in which the child is comfortable and secure

- Observation fits in with the child’s daily routines and activities

- Observation takes place in a real context, enabling you to observe the way in which the child copes positively and negatively with other children in day-to-day activities

- Observation allows you to assess the whole child in her unique, personal surroundings

- Observation helps you to identify what the child does well and the factors that help her to perform well

- Observation allows you to see from the child’s point of view

- Observation allows you to be objective

- Observation allows you to check children’s progress and adapt your activities and practices accordingly

- Observation allows you to be both factual and descriptive.

These are core techniques for every ECD practitioner. You’ll find yourself using them every day in your playroom. The more you use these techniques, the more familiar they will become to you. As you gain more experience, you will find that you use these techniques automatically. You will constantly be observing the children in your care and altering and adapting the learning environment to meet their changing needs.

You’ll find yourself reflecting on your own practice at all times and making the relevant changes needed. This is an ongoing process of observation, reflection, change and growth, which will help you to become an ECD practitioner who is both competent and inspirational.

6.1 Observe babies, toddlers and young children

If you want to observe children differently, you have

to pay attention to the following aspects of your observation:

a) The purpose

b) The duration or length

c) The timing

d) The setting

e) The context.

The purpose of the observation

Your observation should have a clear purpose, in other

words you must be clear about whom you are observing and why. Are you gathering

information for the child’s year-end assessment? Do you want to help the child

develop social skills? Keep your purpose in mind. Don’t be distracted by other

events or children.

The duration or length of the observation

You

will need to decide for how long to observe the child. However, you must try to

make sure that you observe for long enough to provide a true picture of the

child’s behaviour.

The timing of the observation

At which times of the day will you observe the child?

Remember children’s behaviour tends to vary over the course of the day. You may

want to observe the child several times during the day. Or you may want to

choose times that match the child using particular skills, for example social

skills or gross motor skills.

The observation setting

In a baby care facility,

you would observe the baby:

- While you are changing and feeding her

- While she is playing with toys or interacting with you in play

- While she is being quiet, inactive or sleepy

- While she is responding to other people or children in the environment.

6.1.1 Methods of observation

When

you observe toddles and young children in an ECD centre, the different settings

that are available would be the creative art area, discovery area, book area,

fantasy area, puzzle area, outdoor play area and so on. You may also want to

observe the child in settings in which there are different kinds of

interactions - with adults and with parents. Again, this will depend on the

purpose of your observations.

If you want to check which factors encourage the child to perform well and which factors limit her performance, you’ll need to select settings and time in which her performance is at its best as well as those when her performance is at its worst.

If you want to observe the child from a holistic point of view, you’ll need to select a variety of different settings, different activities and different times. You may also ask the child’s parents or caregivers to observe her at home. Make sure you explain the purpose behind the observation clearly. In this way, you can add additional information from the home setting.

The context of the observation

You will have to observe and take note of any

contextual information that may have an effect on the child being observed.

Contextual information include:

- The child’s age

- The time of the day

- Environmental factors

- The child’s health and equilibrium.

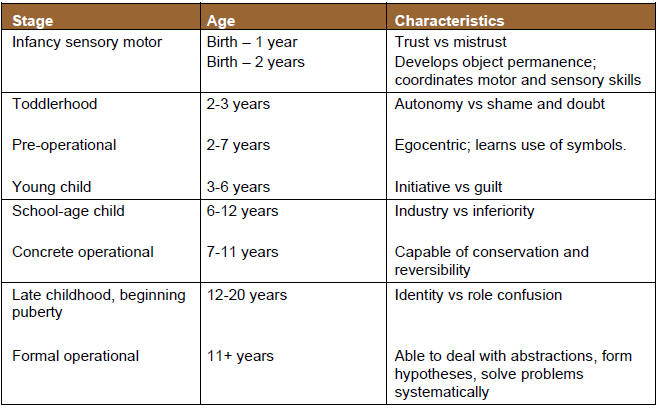

The child’s age

Knowing the child’s age can help you to reflect on the developmental

appropriateness of the child’s behaviour. Your knowledge of the stages of

social and intellectual development is important for you to be able to judge

whether behaviour is appropriate for a particular age or not.

Checking on a particular skill, you need to choose a setting or activity that requires children to use this skill. Then observe three children per day, each for five minutes. Observe each child twice if there is enough time.

To observe the child holistically, you could focus on one child per day. Observe the child for five minutes in each different activity in the programme or each setting.

6.1.2 Ensure that

observations contribute towards assessment of individual development

When you observe in order to assess a child, you must take into account

the zone of proximal development.

This term was used by the psychologist Vygotsky and refers to the difference

between what a child can do alone and what she can do with help. What children

can do on their own is called their level of potential development. Two

children might have the same level of actual development, but given the right

help from an adult one might be able to solve many more problems than the

others. When you are observing the baby, toddler or young child, you must

observe both what the child can do alone and what she can do with help. The

stages overlap at times and it may be helpful to refer to the next stage if a

child shows proximal development (can do those tasks in the next stage with

help).

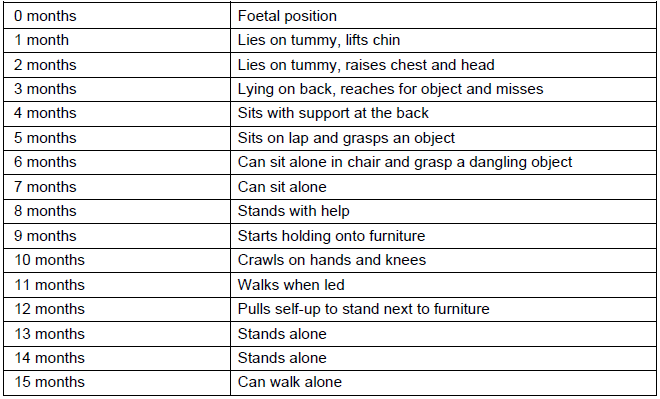

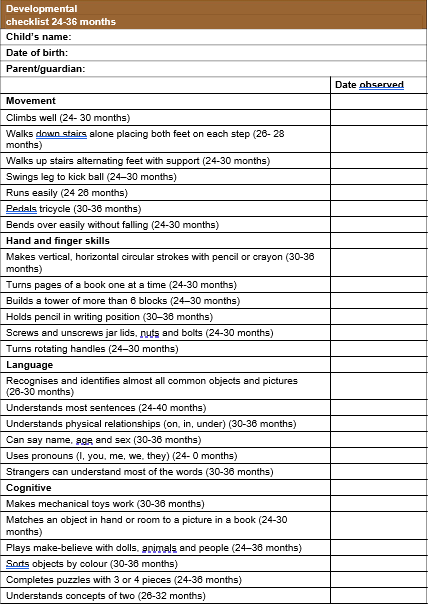

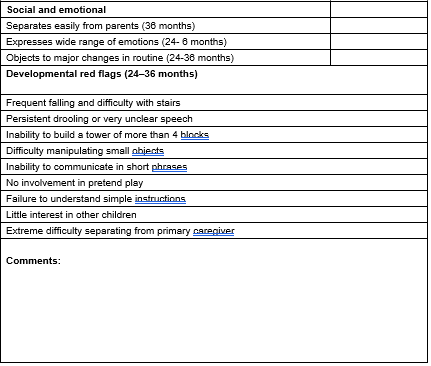

From infancy to adolescence:

When you make observations of babies and toddlers, you may use the reference chart provided below to check whether the child is reaching his/her milestones at the appropriate time.

Infant physical developmental milestones

Observing, in the ECD context, means looking, listening and asking questions. When you look at a child you should have in mind a checklist of her age, her family background, her mood on that day, or any other information you already have about her.

Begin by observing parts of the child’s behaviour by looking. Looking must be done actively so that you are actively trying to find out anything and everything about the child simply by observing her. You should keep an open mind and be willing to be surprised by new information. (See also Unit 4 on minimising bias.) This is an active and conscious seeing of the child. You should then make notes of what you see, as soon as possible.

Listening should also be done actively and with an open mind. This can be done overtly (openly), so that the child knows you are listening, for example when you engage her directly or she is aware that you are present. Alternatively, your listening could be done covertly (secretly), perhaps from an adjacent room or at a distance in the playground. You may want to listen to a conversation or play interaction between the child and a playmate. Your attention should be focused on the verbal (and pre-verbal sound) interaction so that you can later make notes. You may even be able to make notes while the interaction is going on if you are not part of it.

Active questioning means asking open-ended questions for the child to respond to. Examples of such questions could be:

- Can you tell me what you see on this page of the book? What’s happening to the dog in the picture? (o assess language skills and understanding of meaning)

- What should we do with Gugu’s hair band that we found under the swing? (to assess moral, social and emotional understanding)

- Will you please pack all the blocks away into this box? (to assess gross motor coordination, ability to hear and understand simple commands, concentration span, positive response to caregiver).

Rotating your observation

Develop

a system that will allow you to observe every baby, toddler and young child in

your play group or care facility. You can do this best if you rotate your

observation.

In the next section, you’ll learn how to keep observation notes.

6.1.3 Carry out observations in a way that minimises

bias and subjectivity

As a

practitioner you’ll have to decide for yourself which kind of observations are

most appropriate in different circumstances.

1. Types of observations:

a) Factual and descriptive

observation

b) Participant and

non-participant observation

c) Overt (visible) and

covert (hidden) observation.

a) Factual observation

Sometimes when you observe children, you may be looking for clear,

factual information, e.g. “Can Mpho count to 10?’, or “Can Nomsa hop on one

leg?†Usually your factual observations will give you information like “yes†or

“no†as an answer, or a number.

b) Descriptive observation

At other times you want to observe in a more

open-ended way. You may need to draw on your own thoughts and opinions to

describe and interpret what you see. Your observation findings are more likely

to take the form of a description, including questions and descriptive

observation findings: “How popular is Nomsa with her peers?†or “Can Mpho

complete activities independently?â€

2. Participant and non-participant observation

a) Participant

observation

When you are engaged in participant observation, you

observe the child while actively participating in a few activities with him or

her. As a participant, you will be able you observe the child closely, ask

questions that may provide additional information and probably gather a large

number of observation notes in a short time.

b) Non-participant

observation

In

the case of non-participant observation, you observe the child without becoming

actively involved in the activities yourself.

3. Overt and covert observation

a) Overt observation

Overt means openly. During overt observation, you make observation notes

openly and the child is aware that she is being observed. You are aware that

the child may behave differently because she knows you are observing her.

b.)Covert observation

Covert means hidden. During covert observation, you observe the child

without allowing her to become aware that she is being observed; you make notes

privately, when the child is no longer present.

You should use these different methods in a flexible way. Use your common sense. For example, if you want to observe Tumi’s interaction with peers, your observation techniques should probably be descriptive, non-participant and covert. Why? You’ll need to describe the way in which Tumi interacts. If you participate in activities with Tumi, he will probably interact with you rather than with his peers. If you make it obvious that you are observing Tumi with his peers, he will probably become shy or show off.

6.1.4 Ensure that

observations are guided by given frameworks, assessment guidelines or

instruments

Observations

are part and parcel of the method of ECD. Therefore observations should be done

from an assessment mindset. The tools that are used to record and assess the

child must be of a high standard.

Anecdotal records

The

simplest form of direct observation is a brief narrative account of a specific

incident – this is called an anecdotal record. Anecdotal records are used to

develop an understanding of a child’s behaviour. Anecdotal records do not

require charts or special settings. All you need is paper and pen to document

what happened in a factual, objective manner. The observation is open-ended, and

continues until everything has been witnessed.

During your observations, you will record how children communicate, both verbally and nonverbally. You will record how they look and what they do. Physical gestures and movements should be noted. You will also detail children’s interactions with people and materials. Record as many details as possible.

Contents of anecdotal records:

- Identifies the child and gives the child’s age

- Includes the date, time of day, and setting

- Identifies the observer

- Provides an accurate account of the child’s actions and direct quotes from the child’s conversations

- Includes responses of other children and/or adults, if any are involved in the situation.

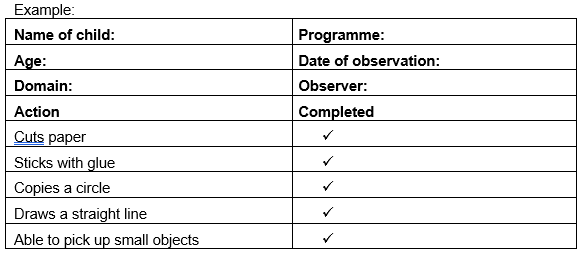

Checklists

Another

form of assessment is the checklist. Checklists are designed to record the

presence or absence of specific traits or behaviours. They are easy to use and

are especially helpful when many different items need to be observed. They

often include lists of specific behaviours to look for while observing.

Depending on their function, they can vary in length and complexity. Checklists

may be designed for any developmental domain — physical, social, emotional, or

cognitive. A checklist that is carefully designed can tell a lot about one

child or the entire class.

Participation chart

A participation chart can be developed to gain information on specific

aspects of children’s behaviour. Participation charts have a variety of uses in

the classroom. For instance, children’s activity preferences.

These three samples (anecdotal records, checklists and participation charts) are only the tip of the iceberg for assessments. The bottom line is that using proper formats for recording and observation is critical to keep track of progress and possible interventions where needed.

6.1.5 Ensure that

observations are continuous, based on daily activities and provide sufficient

information to establish patterns of development

At the beginning of each year, initial assessments need to be performed.

This will provide a baseline to use for each child. Culture, economic status,

and home background will impact each child’s development. Therefore, the

purpose of an initial assessment is to get a “snapshot†of each child in your

class.

Ongoing assessments of individual children as well as the group need to be performed regularly. This may take more time, but it will also provide more comprehensive information. This will be useful in tracking each child’s progress and recording change over a period. It should provide evidence of a child’s learning and maturation. These observations will assist in the modification of resources in the classroom environment if needs be.

Ongoing assessments may happen during classroom activities. Watch children as they work on art projects and listen to them as they tell stories. Observe children as dress up or play with toys. Listen in on children’s conversations. Take notes without being obvious during free-choice activities. This is when children are most likely to reveal their own personalities and development. These notes will provide significant assessment information.

6.1.6 Ensure that

observations cover the full spectrum of activities in the routine or daily

programme

To be

an authentic assessment, observations must be done over time in play-based

situations. This type of assessment is best because it is the most accurate. It

is used to make decisions about children’s education.

In order to ensure that the observations are accurate, the full spectrum of activities must be able to observed on a children’s developmental status, growth, and learning styles. Therefore there needs to be observation tools within the structure of your daily activities.

Proper assessment is best done when children are performing tasks in natural settings. Ensure that you include all developmental areas — physical, social, emotional, and cognitive. The information that you gather should indicate each child’s unique needs, strengths, and interests. You will also gain an idea of progress over time as you chart your findings.

6.2 Record observations

As an

ECD practitioner you will need written observation notes on all the babies,

toddlers and young children in your playgroup. If possible, you should record

your observation notes at the time of the observation. If this is not possible,

for example because your observation is covert, write up your notes as soon

afterwards as possible, so that your observations are still fresh and clear.

Your observation notes should:

- Provide facts, accurate details and careful descriptions

- Detail the following information:

- The child’s home language

- The date

- The duration

- The time

- The setting

- The method of observation

- Describe what you observed of the child’s behaviour

- Include relevant comments or exchanges made by the child

- Explain any contextual factors that might have affected the child’s behaviour.

Developing your own

shorthand

You

may need to develop a form of shorthand, so that you can make notes quickly and

easily. Tips for quick note taking:

- Use quotation marks to record the child’s actual words.

- Use a number in brackets to indicate behaviour that is repeated

- Use a single first letter instead of the child’s full name

- Use abbreviations (e.g. = for example; & = and)

- Create your own abbreviations for frequently used words or phrases (FMS = fine motor skills; SS = social skills).

Analysing observation

notes

When

we analyse, we examine or think about something carefully in order to

understand it. When you analyse your observation notes, you’ll need to draw on

your understanding of child development. Some behaviour may seem problematic,

but when they are viewed within the context of what is expected of a child

developmentally within that age range, you may discover that the child’s

behaviour is developmentally appropriate.

When you analyse your observation notes, you should:

- Describe the behaviour you observed

- Explain what you think about that behaviour

Here are examples to show you what you need to do for each step.

EXAMPLE

a) The behaviour you

observe

You

may think that Moni may have developmental delay because he has not started

crawling yet at age 10 months. He is a very fat baby. When you observe his

behaviour, you notice that he tries to crawl but he rocks back into a sitting

position. He does not easily stand with help.

OR

Nono cannot stay still during story time. When you observe her behaviour, you record that during a 15-minute story, she got off her cushion seven times, for about 30 seconds each time – a total of 3 minutes and 30 seconds.

b) What you think about the

behaviour

You

may think that Moni is not able to crawl because he is a fat baby, but if he

still has not crawled but has begun pulling himself up to stand at 12 months,

then he is one of those babies that has skipped the stage of crawling. Or he

may start crawling late (11 months) because of floppy muscles (a genetic

condition). It may be necessary for him to have a developmental assessment from

a paediatric specialist at a later stage to check that he has no other gross

motor problems. Simply continue to observe his motor coordination to see

whether he crawls later or begins to pull himself up to stand.

You may think that Nono needs to be physically active to keep her concentration levels high. However, if Nono behaves this way only at story time, she may have difficulty understanding the story. This could mean that Nono has a short concentration span. Or it could mean that she struggles to understand in a language that is not her first language.

6.2.1 Ensure that the

records accurately reflect the observations and are culturally sensitive and

bias free

When

you work as an ECD practitioner, observing children it is a natural and normal

part of what you do. You observe children to see if they are bored with an

activity and whether they need a break. You observe children to see whether

they have managed to follow your instructions. You observe children to check

that they are sharing and playing cooperatively. As you observe, you make small

and subtle changes to your learning programme to match to the children’s needs.

This is called observation for

facilitating learning and development. Observation for formative assessment feeds into the natural

cycle of assessing, planning, implementing and reflecting within the learning

programme:

- Assess

- Plan

- Implement

- Reflect

- Assess

- Plan

- Implement

- Reflect

- Assess

- Plan

- Implement

- Reflect

- Assess

However, we also observe children for another purpose, namely to assess their progress within the ECD playroom. This is summative assessment. The people who want to know about this progress include your supervisor, the team of colleagues, parents, and other service specialists.

The observations you record for the purpose of assessment may be used for:

- Assessment of development of babies, toddlers and young children

- Referrals

- Designing of programmes and activities

- Evaluation of activities and programmes

All the records we have discussed so far, namely anecdotal records, checklists, rubrics and reports, can be used for assessment development. This was discussed in the previous learning unit.

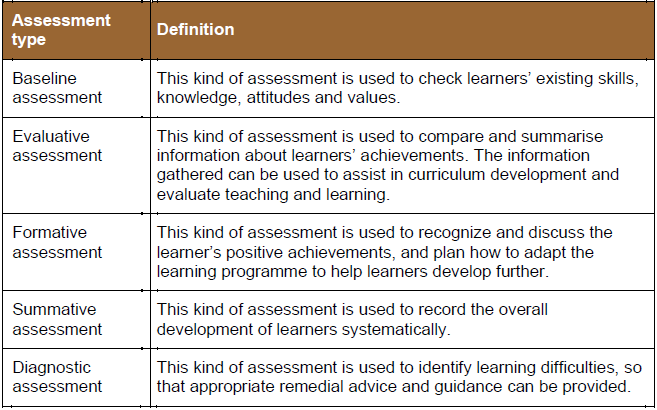

In order to use your recorded observations for assessment, you need to define first what kind of assessment you want to make, using those records.

6.2.2 Ensure that the

records are structured in a clear and systematic manner, and include any

information that may be needed for tracking progress

The children in your care are constantly growing and changing. Their

growth may go through spurts, or they may take a long time to learn a

particular skill or recover from an emotional upset at home. For example, Khosi

may be feeling very angry because his father has moved to another town and remarried,

leaving him behind. Your observations should chart this process of change, so

that by the end of the year you have a picture in your mind of the high points,

the low points, the fast-paced weeks when the child’s language or co-ordination

suddenly leaped forward and the difficult times when the child struggled with

relationships or impulses. “Recording should be done continuously across

activities.â€

To create an orderly and comprehensive description of all these changes it is necessary to keep more structured records than simply anecdotal notes about things that happened.

Some recording tools which can be used for assessment in ECD classroom are:

- Checklists

- Profiles

- Questionnaires

- Rubrics

Checklist

You

have been introduced to a checklist. Be aware that most people tend to favour

the average or middle score when using checklists e.g. good, on a rating of

1–4. It is important to think carefully about each score and to make it as

accurate as possible, rather than going for the average or middle score most of

the time.

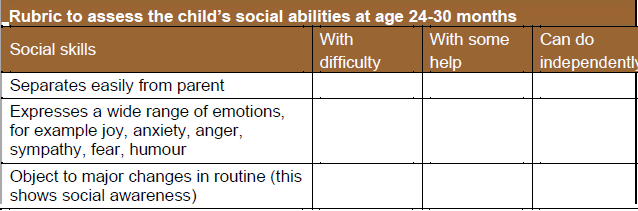

Rubrics in observations

A rubric is a grid that is used to make a quantitative assessment. It

may be used to assess children’s learning and development. A rubric usually

itemises the skills or qualities in that which is being assessed.

While you may use rubrics and checklists within the formative assessment, their purpose here is not so much to evaluate a child’s mastery of a particular learning outcome as to provide feedback on the child’s overall learning and development, as well as on the effectiveness of the ECD programme itself.

We usually use rubrics to make quantitative, rather than qualitative assessments. For example, we may use a grading system to assess how competently a child manages various fine and gross motor skills.

Guidelines for creating a rubric: The following steps will help you create new rubrics more easily:

- Identify what it is you want to measure. Make this the name of your first column

- Identify the levels at which you want to measure it. Use these levels as headings for your remaining columns (for example “Screw 1,2,3†or, as in the example)

- In the first column, describe the behaviour or skill you want to assess. Use simple language and use a new row for each idea

- See if you can break down the items in the first column any further to make the rubric easier to use. For example, under “Skills†we could break down the items further to expresses a wide range of emotions into positive emotions and negative emotions.

6.2.3 Ensure that

records are useful for contribution

In the course of running your playgroup or simply teaching at a large day

care centre, you may be asked to report on a particular child. The purpose of

the report is usually to provide a summary and evaluation for others to

understand the child’s progress. Usually, such a report has the following

structure:

- Name and identifying details of the child and the purpose of the report

- Brief summary of observations (a copy of the original observations can be made and attached as an appendix or addition, at the back of the report)

- Discussion and evaluation of observations, evaluating the child’s skills, abilities and behaviour against the developmental milestones

- Conclusion and recommendations, indicating the next step or further help or treatment for the child

The report can also be used as a summary of information, simply for feedback to colleagues who need information. Some examples of reports on developmental assessments are:

- For school readiness

- For referral to a specialist e.g. audiologist to assess the child’s range of hearing

- For discussion with the team members e.g. about a child who has emotional and behavioural problems which must be addressed by every member of the team in working with that child

- For parents who may want a useful summary of their child’s progress to help with transfer to another day care centre

- For end of year evaluation in order to move a child to a more advanced group in the new year.

An important part of writing a report is that it gives you an opportunity to reflect again on your observations. By the end of the report writing process, your understanding of the child should be clear and you should be familiar with all the information.

Present the report

Prepare to present the report by reading it over and asking yourself

questions about important issues. This preparation is an important part of

report writing. You should be able to answer questions about your observations

and your recommendations, when you have presented the report to a meeting of

colleagues.

Steps to follow when you want to use your records to assess development:

- Make a baseline assessment with anecdotal records and checklists

- Use rubrics and checklists for formative assessment

- Use written reports to refer for diagnostic assessment

- Use an assessment rubric for summative assessment.

Look at each step:

1. Make a baseline assessment with anecdotal records and checklists

You will need your observation notes and anecdotal records, as well as a

developmental checklist when the child first enters the preschool or baby care

centre, to check the child’s existing levels of learning and development in a

specific area. In other words, you want to establish what knowledge, skills

values and attitudes a child already has. You use baseline assessments to help

you determine how to plan your learning programmes to best meet the

developmental needs of the child. You also use this type of assessment to help

you measure a child’s progress over a period of time.

2. Use rubric and checklist

for formative assessment

Formative assessment is ongoing. The purpose of formative assessment is

to provide feedback of what children are learning; formative assessment helps

the child to recognise achievements and possibilities for further development.

While you may use rubrics and checklists within formative assessment, their

purpose here is not much to evaluate a child’s mastery of a particular learning

outcome as to provide feedback on the child’s overall learning and development,

as well as on the effectiveness of the ECD programme itself.

Always supplement your use of rubrics and checklists with at least two anecdotal observations so as to get a closer view of the child’s abilities. This will add a qualitative perspective and a more holistic understanding to the quantitative assessments of grids or checklists. Your insight and knowledge of the child is essential to supplement these records.

3. Use written reports to

refer for diagnostic assessment

When you refer a child to a specialist for a diagnostic assessment, you

are relying on your records of development assessment to identify potential or

existing learning difficulties that may require specialised interventions, e.g.

occupational therapy or physiotherapy. First check to see whether the learning

activities you have provided are developmentally appropriate. For example, a

gifted child may become bored with tasks that are too simple and may

consequently not perform well. A diagnostic test will usually reveal the origin

of the problem. Professionals are better equipped to conduct diagnostic assessments and the ECD

practitioner may want to consider referring a child to the relevant

professional for diagnostic testing. The written report is the tool to use for

such a referral.

4. Use an assessment rubric

for summative assessment

Summative

assessment helps the practitioner to develop an overall assessment of the child’s

learning and development according to specific criteria. For example, a

summative assessment would be used to check whether a child has acquired the

knowledge, skills, values and attitudes required to move from a Gr R playroom

to school readiness in a Gr 1 classroom. Because summative assessment measures

the child’s progress against a range of specified learning outcomes, it is

usually done by means of a closed-ended assessment tool like a checklist,

rubric or assessment grid.

Using records in the design and evaluation of activities

When you conduct an evaluation, you survey the work of the children in your playroom. You should do this once a term. You use your survey of children’s work to help you evaluate the effectiveness of your learning programme. In other words, the purpose of an evaluative assessment is to evaluate the effectiveness of your own learning programme and your teaching.

By surveying your records of all the children once a term, you may notice a trend in areas of development in which many children are struggling. For example, if your records show that 80% of the children in the group are struggling with fine motor development, you will need to check that your activities are interesting, stimulating and can be performed by most of the children, while still offering scope for change or extension. Perhaps you need to make your activities simpler and yet more stimulating until you can check on the children’s acquisition and development of skills again and then increase [or raise] the level of difficulty of the activities. Perhaps these are activities which you find boring or difficult to manage without an assistant and so you tend to cut down the time allowed to the children to do them.

Protocols for referrals

Your

report may be very valuable to a specialist e.g. speech therapist or

physiotherapist, who must work with the child to correct a developmental

problem. For this reason it is most important to be accurate with your

observations. Do not try to predict the outcome of your conclusion and

recommendations before you get to that part of the report. The meaning and

validity of your observations may look very different when you review your

observations as you write the report. The parents are also important audience

for a report, so keep the language and explanations clear and simple. In the

next unit you will find out more about presenting your report to the parent. Do

not add jargon to try to impress anyone. Never forget that the main purpose of

the report is to communicate clearly about the child, for the child’s sake.

6.3 Give feedback on

observations

In

this section you will find out how to present your observations and records to

the target audience in the most effective way. The information you have

collected about the individual baby, toddler or young child remains

confidential and should be handled carefully. You should evaluate your notes,

reports and conversations about the child with sensitivity and handle your

verbal interactions with parents sensitively too. Present written reports to

the parents only after you have discussed the terminology with them. Make sure

that your written reports for referrals to specialised services are accurate.

Store the recorded observation on which these reports are based safely in case

you (or other staff) need them in future.

Keep in mind the following ways to maintain confidentiality when discussing a child in your care:

- The child should not be present or within earshot when he or she is being discussed

- Only the relevant team members, the parents or the relevant service specialists who are going to receive your information should be included in any discussion of your observations and assessments.

Information should be filed and stored in an orderly and secure way, so that it does not get lost or abused by people who have no understanding of the issues.

6.3.1 Give feedback using appropriate feedback mechanisms and in

accordance with confidentiality requirements

In

this unit we help you to build on what you’ve already learned about reporting

to families on children’s progress. We will focus on:

- Oral feedback in an interview situation (formal, or informal)

- Formal written feedback in a report.

We will highlight ways of ensuring that the methods you use to discuss children’s progress with family members are:

a) Appropriate to the

setting

b) Supportive

c) Meaningful to the

families.

Let’s examine each of these requirements in turn.

Contextually appropriate

reporting (oral feedback)

Parents and caregivers are usually sensitive about

their children and their progress at school. For this reason, it is appropriate

for you to take extreme care when you report or give feedback on children’s

progress. You should make sure that the feedback you give is appropriate to the

setting or context.

For example, if you are having an informal chat with a parent, it may be appropriate to mention an area in which the child has improved. So, if a child previously been struggling to complete jigsaw puzzles and had been avoiding puzzles as a consequence, you could say, “Stephan seems to be able to build jigsaw puzzles now.

Can you believe it? Today he asked if he could do a jigsaw puzzle during free play!â€

This is an anecdotal form of reporting, which indicates positive progress in a conversational way. If another parent or caregiver overhears this conversation, it will not throw up issues of comparison between children, as the comment is so specific to the child at hand. In addition, if the child concerned or another child overhears the comment, it is still not harmful, since you have probably commented on Stephan’s eagerness to him in front of the playgroup already. So, this is an example of a feedback comment that is appropriate in an informal, conversation setting.

Most often, however, the ECD practitioner should try to give structured, meaningful feedback on the child’s progress at a formally arranged parent interview. In this context, the child concerned is not present, so he or she will not be affected by overhearing what is said. In addition, no other parents, caregivers or children are present, so the interview context is protected and confidential. Since you will set aside time for this particular interview, you will ensure that there are no interruptions or distractions, enabling you to give the child’s family your undivided attention. In this way, the parent interview provides a highly appropriate context to offer substantial feedback to the child’s family.

What do you do if you have a fairly significant assessment issue to discuss, but your parent interviews are not scheduled for some time? The best way to handle this is to set up a time to telephone the parent or caregiver. Ask the parent or caregiver to choose a time when the child will not be present to overhear the conversation – usually after bedtime is a good time. Alternatively, set a special parent interview to discuss the issue. Make sure you conduct the interview in a separate room, of earshot of other children or parents. In this way, you show parents that you take confidentiality seriously, and that they can trust you.

Supportive reporting in

an interview with parents

When you provide feedback on a child’s progress,

remember to be supportive and communicate constructively. You can do this in

three main ways, namely by:

- Emphasising the child’s strengths and achievements

- Being sensitive and caring about a child’s difficulties

- Being sensitive to ethnic and cultural differences which may affect the child’s performance in activities

6.3.2 Ensure that feedback is clear and relevant to the child’s

development

Always

begin a feedback session by focusing on the child’s areas of strength and

achievement. Every child shines in particular areas. For example, the child may

be a highly inventive thinker, she may enjoy and excel in activities that

require detailed planning and fine manipulation, or she may be extremely caring

and generous with others. Remember, families know their own children well, so

they also know their children’s strengths. If they hear you affirming the child’s

strengths with which they are already familiar, they will have more respect for

your ability to identify areas of difficulty. In addition, all parents like to

have their children affirmed and praised. This helps them to feel proud of the

child’s achievement and to feel more competent as parents. Make sure your

reporting includes plenty of positive feedback, so that parents feel supported

and feel positive towards their child.

When you report on a child, you must also draw parents’ attention to their child’s areas of difficulty. Again, although parents can be blinkered about their children, at some level many parents would already have noticed that the child struggles with everyday routine tasks like brushing teeth, eating with cutlery and tying shoelaces. Most parents will have observed that the child struggles with tasks of this nature, so your feedback about the child’s fine motor function being weak may not come as a total surprise.

However, even if parents are prepared, it is not easy for them to hear that their child is struggling. If parents are unprepared or resistant, it can be even more difficult to help them to hear, understand and accept that their child has problems. Often the child’s difficulties may be well within the acceptable range for the child’s development age, but weaker than the child’s other areas. You can explain this to the parents to put their minds at rest. Each child has some areas that are weaker than others. Otherwise the child would have no strengths either, but would achieve equally in every area.

Parents can be helped to understand that we are all more competent in some areas than others and this often relates to our personalities, learning styles, likes and dislikes and the activities to which we have been most frequently exposed. If you provide a context like this, parents will more readily accept that their child has areas of relative weakness. You can then move on to discussing strategies to help the child with these difficulties.

At times, a child’s difficulties may require specialised assistance and you will need to use the parent interview as the context to suggest referral to a professional, for example a psychologist, occupational therapist or physiotherapist. Again, emphasise that the professional will be in a better position to judge whether the child needs special attention or early identification and intervention. Also, help parents to understand that remedial interventions are highly effective at a young age and that by making the responsible decision to assist the child while he or she is still young, the parents can help the child to cope more successfully when he or she reaches primary school. You should discuss with the parents your formal written referral report to the professional, so that they understand everything you are saying about the child. (See section (c) below for details of the formal written report.)

Be sensitive to parents’ feelings. Remember that people show their feelings in a wide variety of ways. They may become defensive and angry; they may deny the problem, or they may feel overwhelmed and guilty. Make it okay for the parents to express their feelings in whichever way they need to. Be caring. Say something like “This has been a shock for you. You must be feeling very upset/angry/sad. That’s okay. It’s always hard to hear that your child needs help.’ In this way you make it possible for the parents to be part of a constructive outcome for the child.

6.3.3 Give feedback with appropriate sensitivity to diversity and

emotions

Parents,

whose ethnic or cultural group is in the minority at the playgroup, may be

especially sensitive to negative feedback about their child. You should give

positive and encouraging comments about the child’s progress first and then

show that you accept them and the child by acknowledging their culture. Without

blaming the culture for any possible difficulties, explain to the parents that

the child’s innate ability may need more patience and encouragement to blossom

in an environment which may be different from her home culture. When sharing

information about a child whose difficulties may be due to having a culture or

language different from that of the playgroup, be sensitive to how much may be real developmental delay and

how much may be language or culture related, which will improve as the child

adapts to fit in with the group (and the group adapts to include her more and

more). The parents could be encouraged to repeat some relevant activities at

home in their own language, to give the child a sense of familiarity with the

activities.

6.3.4 Ensure that the

type and manner of feedback is constructive and meaningful

Make sure that the reports you give on children’s progress are

meaningful. This means that you make sure that your reports are an authentic

reflection of the child’s strengths and areas of difficulty and of the child’s

learning and development over a particular period of time. If you choose the

most appropriate assessment methods and the correct assessment tools, your

assessment reports will be meaningful to families.

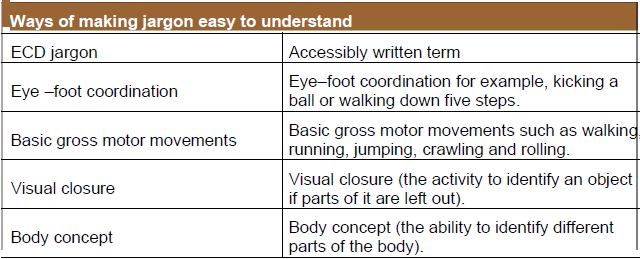

Another way to ensure that your assessment reports are meaningful to parents is to make sure they understand the criteria used to assess their children. In many ECD centres it is usual to give parents an assessment report on their child twice a year. Often these assessments reports take the form of grids or rubrics, with learning outcomes for the main developmental areas. These learning outcomes can be difficult for parents to understand, yet many ECD practitioners do not make an effort to eliminate jargon from their assessment grids, nor do they explain these assessment criteria to parents. This is not an example of meaningful reporting. If the parents do not understand the terminology used in the assessment criterion (for example, “crossing the midlineâ€), how would this assessment report would have any meaning for them? Remember, some parents may not want to show their ignorance, so they may feel too embarrassed to ask you to explain terms that are specific to ECD, or assessment criterion that are difficult to understand.

You can help to explain these assessment criteria to parents in two ways. Firstly, you can make sure your written assessment report, rubrics or grids are free of jargon. Secondly, you may sometimes want to include an important ECD term and if so, make sure you explain what the term means by providing an example to help parents understand.

Ways of making jargon easy to understand

Secondly, you can explain difficult terms or concepts face-to-face during the parent interview. It is good for parents to have the interview before handing out the written assignment reports. In this way you have a chance to explain the assessment criteria to parents before they see the reports. You then have an opportunity to clear up any difficulties or areas of confusion, so that when parents sit down to read the reports they understand the terminology. This will help to make the assessment report more meaningful for them.

6.3.5 Provide sufficient

information to enable the purpose of the observation to be met, and to enable

further decision-making

Before

you give feedback indicating that a decision must be made, check the criteria

on which the decision must be made. For example, if you know that a decision to

send Mpho for a hearing test rests on the criteria of her lack of response in a

group setting, then you need to provide evidence of trying to get her attention

in a group setting four or five-times without success. The number of times you

observe the same responses improves the likelihood that a poor response is a

sign of a problem.

Your information-gathering about the child is a continuous practice and as such should provide you with plenty of information in your observation records. The whole child should be observed in the whole programme. The observation should always include personal anecdotal observation, so that your experience of the child and knowledge of her playgroup is much bigger than simply checklists and rubrics.

To summarise: the information should be sufficient in terms of both quantity (number of times observed) and quality (personal insight and knowledge about the child gained through interaction and anecdotal record keeping).

Providing sufficient information to interventions referrals and further observations:

You should have enough recorded observations to allow you to make knowledgeable input into a team discussion of the child’s developmental problems. You should keep the collection of records so that you can refer to it at any time. Even if you have written up a report after the observations, you should remain open to discussion of the observations by other professional colleagues.

You may also have to provide feedback to specialised services and any professional help to the child will rely on the foundation of your observations to provide a background to the problem and the child’s functioning.

To sum up, it is extremely important that your observations should be properly recorded, so as not to disadvantage the child or provide misleading information to those concerned. The records should be kept safely so that you can build on and extend them with later observations. There will be further decision-making, relying on your records, as the child grows and progresses out of the playgroup and into Grade 1.

6.4 Use strategies to be

an effective speaker in sustained oral interactions

Being an effective

speaker also requires input from your ECD colleagues. The following strategies

may be used for self or to assist a colleague to improve.

Being able to have effecting sustained oral communication skills will enable you to always have clarity within your ECD setting. These are some effective tools to use in order to refine your communication:

Body language

Maintain

a relaxed posture without slouching no matter what the listener is doing or if

you are the listener ensure that you do this. Some other tools would be:

- Maintain a comfortable sense of eye contact

- Nod your head to indicate that you are listening

- Keep your hands in a clasped or open position and do not cross your arms

- Keep nervous habits to minimum such as nail biting, fidgeting or anything that the person communicating with you will view as a distraction from their conversation.

Speech and attentiveness

Be

clear and concise when speaking. Get to the point when discussing important

matters. Ensure that they are listening by asking if they understand you, and

be willing to further explain any of your points. In addition, one of the most

important aspects of verbal communication is the ability to practise active

listening. This is not just actively waiting to talk. Always make mental notes

of key points when someone is speaking to you. Thus when you can reply, you can

respond effectively. When listening think about the exact words that they are

saying, this will ensure that you will understand at least 75% of what they are

communicating.

Communication consistency

Excellent communicators

practise the ability of consistent communication by remaining open to

communication. Be bold and voice concerns or difficulties. This kind of

communication style will prevent the small issues from becoming large ones by

making those in your life aware that you are open to discussing issues at any

time.

Patience

Give

people the time and space to say what they need to and remain focused on what

they are trying to communicate therefore indicating that you are willing to act

if needed. By being patient communication need not break down. Control your

reactions appropriately.

If you are unsure of what they are saying, than repeat back to them what you have understood and ask if that is correct. They therefore will be more clear and precise about their needs, assisting you to understand them fully.

Knowledge of formats,

conventions, protocols and contexts

When

communicating, we need to take into account that each format (letter, dialogue,

report, spoken presentation, etc.) has its own conventions (e.g. a

dialogue will mimic natural spoken language, while a presentation to management

will use more formal terminology), protocols (the etiquette or correct

order of doing things) and contexts (i.e. a dialogue will take

place in the context of a real conversation, while a formal presentation will

be required by management as part of the performance management process.)

6.4.1 Show planning of

content and presentation techniques in formal communications

Formal communications need careful preparation, if you

want your audience to listen and possibly enact on what you are saying the

following will ensure that they will see the evidence of you having spent time

researching and planning your topic.

At the start of your presentation:

Identify the audience – The principal of matching the audience aims, within the statement of objectives will be allow them to be reassured that they are understood and that this will not be a waste of time.

Formulate your objectives – This is a simple, concise statement of intent. Focus is the key in this opening statement. Isolate the main topic and to list at most two others that will be covered providing they do not distract from the main one. Ensure that the following is built into your communication:

- Get their attention

- Establish a theme

- Create a rapport

- Administration (details from a business point of view such a previous minutes, etc)

- Use visual aids.

Ensure a structure – there must be a definite flow from one topic to another creating a cohesive communication that the audience is able to follow.

At the end of your presentation:

Summarise the main points of your presentation, ensure that the audience is clear with what to do next if this is the context this presentation is given in. changing the pace and tone of your voice is also a queue to that fact that you are winding down to an end.

6.4.2 Analyse the impact

of non-verbal cues/body language and signals on audiences and use it

appropriately

Your

job as the presenter is to use the potential of the presentation to ensure that

the audience is motivated and inspired rather than disconcerted or distracted.

The five body language and nonverbal skills that deserve attention in

presentation skills: the eyes, the voice, the expression, the appearance, and

how you stand.

The eyes

As

you are delivering, use eye contact to enhance your rapport with the audience

try and do this with each and every member of the audience as often as

possible. Smaller groups are easier to deal with but it can also be achieved in

large auditoriums. Using your glances in the form of a Z starting at the beach

and moving forward then back again allows you to convince each of them

individually that they are the object of your attention. By holding your gaze

fixed in specific directions for five or six seconds at a time you will also

enhance audience attention.

The voice

Aside

from eye contact, the most important aspects for public speaker are projection

and variation. Using a conversation voice will not gain any attention nor will

you really be heard. In normal conversations the listener’s body cues will tell

you if what you are saying has been heard. The best thing to do is SLOW DOWN.

Speak to the audience in a slightly louder voice is a good start. Asking them

if they can hear you does also help. Variation in tone is another aspect that

will keep the audience’s attention.

Expression

A plain

dead pan uninterested facial expression will not win any audience you are

speaking to. Smile often if the topic requires you quite simply: make sure that

your facial expressions are natural, only more so.

Appearance

Dress

the part, dress for the audience. If they think you look out of place, then you

are. Do some research regarding the dress code for your target audience and

dress accordingly. Rather err on the side of neatness (i.e. rather be too neat

than not neat enough)!

Stance

Your

posture needs to convey that you are confident. Use your whole body as a

dynamic tool to reinforce your rapport with the audience. Make sure that your

hands remain in a neutral state; waving them about or fidgeting is distracting.

6.4.3 Analyse the

influence of rhetorical devices and use them for effect on an audience

Good

presentations are full of rhetorical device, intonation (this is the rise and

fall of your voices pitch) and structure are weakened without the all-important

pause. Apply a solid pausing technique to your speeches and you can expect to

become a more effective speaker. Rhetorical devices are the parts that make a

communication work. Separately, each part of is meaningless, but once put

together they create a powerful effect on the listener/reader.

Putting emphasis on HOW you say a word can cause a great impact, such as drawing out a word slowly, saying it softly or loudly. You need to keep your audience engaged. Stressing particular topics or words is also helpful. In this group of devices just as you would use an exclamation mark in writing, using an exclamatory word or phrase will certainly add verve. Such as using one word, with a pause “Sit!†(pause) yes I said SITâ€

When using rhetorical questions, ask a question of your audience and you look for their engagement. Ask a question and pause ... and you have their engagement. They will be engaged then, given them thought. Your pause brings their focus straight to your question. Answer your question. Pause ... and then continue. This can be also emphasised with your body language (non-manual features) facial expression and how you hold yourself.

Using an inclusive pronoun gives an effect of unanimity as it addresses everyone as a whole, whereas it contrasts with exclusive nouns that create distance.

An example would be: ‘what we need’, the ‘we’ being the inclusive noun.

Repetition can be effective in creating a sense of structure and power. In both speech and literature, repeating small phrases can cement ideas in the listeners mind.

Sound-based rhetorical devices add a poetic melody to speeches. This allows your speech to be easier to listen to, a device such as alliteration — repetition of the same sound at the beginning of nearby words e.g. “what was Wendy waitingâ€, “She saw souls soaring†and assonance — repetition of the same vowel sound in nearby words, e.g. “how now brown cowâ€. Creating this kind of rhythm keeps your audience engaged.

Using analogies can also be effective in bringing the point home and it could possibly be the one thing your audience walks away with. Here are some examples:

“The hitchhiker in her scruffy clothes was a guru of travel talk†or a more famous example - “They crowded very close about him, with their hands always on him in a careful, caressing grip, as though all the while feeling him to make sure he was there. It was like men handling a fish which is still alive and may jump back into the water.†- George Orwell, A Hanging.